ACRP Newsletter (December 2025)

december 2025 Edition

Dedicated to McArthur Myers

Every December we take a deep dive into an unknown or lesser known part of Alexandria’s history. This year, the feature story is dedicated to Alexandria Community Remembrance Project Steering Committee Member McArthur “Mac” Myers who passed away on Dec. 4, 2025. Mac was passionate about Alexandria’s history, about lifting up the achievements of this city’s Black residents, as well as acknowledging past tragedies. Mac was persistent about sharing this history and connecting our community across the lines that divide us to heal together for a better future. But that can’t happen, until we know our whole history, as he said, “One city, many stories, tell them all!”

We will, we promise, this one’s for you, Mac.

The Almost Legal Lynching of Albert Hawkins

As October faded into November, the young daughter of a well-to-do Alexandria farmer, who lived near the bridge to Washington, accused a Black boy of upsetting her on her way home from school. A couple of hours later, a mob gathered outside the magistrate's home where Albert Hawkins was being interrogated and charged with attempted rape. Then, in a twisted game of chase, Hawkins endured a harrowing hours-long backwoods hike that ended with the mob closing in as he and the constable reached the Jail on St. Asaph Street at 1 a.m. Tuesday, Oct. 29, 1895.

Morning newspapers promised it wasn’t too late to hold a lynching and suggested it was likely there would be one that evening. But at the Alexandria Gazette, Mayor, Luther Thompson, who was reporter and editor of the local news section, frantically tried to convince readers there wasn’t a lynching in the works and accused the Washington papers of attempting to foment a mob.

Ida B. Wells’ international anti-lynching campaign was gaining momentum and inspiring boycotts against places ruled by mobs. A botched lynching in Roanoke still hung in the air and local officials wouldn’t have wanted the negative attention a lynching would bring to Alexandria. They chose to use the law to satiate the blood lust that drove lynch mobs. They employed a relatively new capital charge, “attempted rape,” and advanced the Hawkins case, to speedily dispatch “justice.” Within 36 hours of his arrival and 48 hours of the alleged assault, a 15 year-old boy was sentenced to die on the gallows. Alexandria’s strategy proved to Virginia’s Governor that prioritizing “justice” and serving it hot would create the perception of due process, quell ravenous mobs, and save Virginia’s reputation. 1

But officials didn’t expect the Black community on both sides of the Potomac to rally to the cause of the Hawkins boy, who had just turned 15 eight days before being taken from his Uncle’s home by a stranger and thrown in jail. They raised money and hired an African American Attorney who held Alexandria’s courts accountable and won Hawkins a new trial. The boy was saved from the noose, but the maximum sentence imposed on Hawkins had a similar effect; his life was essentially forfeited to the system.

Lost Luster

When Gov. Charles Triplett O’Ferrall stepped into office on Jan. 1, 1894, white Virginians’ taste for lynchings had already begun to pickle. Just months before, an attempted lynching of an innocent Black family man who lived on the edge of Roanoke resulted in the deaths of eight white men and numerous injuries at the hands of the militia. The mob then turned on their own community. White owned businesses and homes were endangered, and death threats were issued against the Mayor, the Commonwealth’s Attorney, and the local Judge.

As 1894 rolled on, Ida B. Wells’ campaign, which exposed the lie that only rapists were subject to mob law, was fortified by many of Great Britain’s Lords, Ladies, and Editors, and was pushed into the pulpits and presses of the Northern States. All of a sudden, proposals for investigations and boycotts - both foreign and domestic - proliferated against the southern states. Lynching had become bad for business.

Alexandria, which grew up around Hugh West’s tobacco inspection warehouse at the foot of Oronoco Street, had been pro-business from the start. During the War of 1812, city leaders surrendered the town and all the ships in port (including their cargo) to the British in exchange for the enemy not setting their shops and homes ablaze. In 1847, white powerbrokers returned Alexandria from D.C. to Richmond’s rule to preserve the domestic slave trade, which was central to the city’s economy. So, it isn’t surprising that Alexandria would play a role in shifting the state from mobocracy to capital punishment. And in so doing, help establish Virginia’s reputation as a “moral, law and order, safe for business state” while ushering in an era of legal lynchings. 2

Kevin Hegg, author of “Uneven Justice: The Origin and Practice of Legalised Lynch Law in Jim Crow Virginia,” explains the pattern for skirting due process that was first laid down with the Hawkins case,

“A legal lynching begins with a quick indictment and trial and ends in an almost certain execution. The trial unfolds under pressure from a threatening white mob embedded in the courtroom or surrounding the courthouse.” 3

From “Riot at Roanoke” to the “Roanoke Tragedy”

On Wednesday, Sept. 20, 1893, in Roanoke, Va., an older white woman accused a Black resident of holding a razor to her neck, threatening to kill her, and robbing her. Mrs. Henry Bishop said her assailant left her unconscious on the floor. A police detective brought Thomas Smith to her and Bishop agreed he was definitely the man who attacked her. Bishop’s son was soon leading a mob to extract “justice.”

Roanoke Mayor Trout urged calm. He asked the men and boys outside the police station to let the law take its course. The Commonwealth’s Attorney, A.H. Hardoway, and Roanoke’s Light Infantry were also on hand. As the mob grew more agitated, the militia warned them - multiple times - they would use their weapons to keep order. The militiamen held their fire until a swell of determined white bodies crashed against the jailhouse doors. An explosive volley from above killed eight men and injured scores more. After the wounded and dead were cared for, shocked residents formed a new mob. Town leaders and pastors tried to assuage the public’s anger. Judge Woods promised a quick indictment. He told the crowd Smith had been moved to safety and the disgruntled slowly disbanded. But that was a ruse, and at 5 a.m., 20 men went to the jail and demanded their man. This time, the Police handed Smith over without a fight. When the lynchers left Smith’s lifeless body, they slung a wooden sign around his neck that read: “This is Mayor Trout’s Friend.” 4

An initial inquest found no one was responsible for Smith’s abduction and gruesome murder. His body was removed and burned in front of at least 1,000 angry spectators whose indignation at the militia firing on white people grew fiercer by the minute. There was talk of harming local officials and burning down the town.

“Threats of vengeance have been openly made against the mayor and the militia for attempting to maintain the law,” wrote the Alexandria Gazette’s Harold Snowden in an article titled “Roanoke Tragedy.” Mayor Trout, who had been shot in the foot, and RLI Capt. Bird were driven out of town by their own constituents.

Just days later on Sept. 25, with the Roanoke Mayor in hiding in Richmond and the aftermath of the lynching event still visibly present, Charles Triplett O’Ferrall arrived in town. Somehow, while there campaigning to be Governor, O’Ferrall managed to avoid addressing the crisis engulfing the community. 5

But everyone else was talking about it.

“Some of the northern newspapers are holding up the late Roanoke affair as conclusive proof of the lawlessness and bloodthirstiness of Virginians,” wrote Snowden, adding,“Roanoke is a new town and most of its people are not to the manor born, many of them being natives of the North. The crime for which the brutal wretch who committed it was punished deserved death, but the people of no other State are more emphatic in their condemnation of the manner in which that punishment was inflicted than those born and raised in Virginia.” 6

Across the state, pulpits condemned the disorder caused by the lynchers - the wider community was aghast. At a meeting at Second Baptist Church in Richmond, both church and press joined forces to denounce the practice of lynching. Rev. Dr. R.T. Wilson and the Richmond Daily Times Editor, Joseph Bryan, spoke out against mob justice.

“If revenge is going to take the place of law in heinous crimes, what will be the next step? Where will you draw the line? The barriers once broken down, there is no restraint. If justifiable in one case, why not in another? Any man who takes the law in his own hands is a lyncher,” Bryan said and warned the audience not to dare think it can’t happen in Richmond, because, he told them, it can. 7

Indeed, events in Roanoke shook Virginia’s white establishment out of their complacency toward mob violence; it had spilled into their world, jeopardizing “white public officials, white homes and businesses, and the state's economic interests among Northern investors,” according to Hegg. By the time O’Ferrall stepped into the Governor’s mansion on Jan. 1, 1894, criticizing lynching had become acceptable and almost expected. 8

At his inaugural address, Gov. O’Ferrall stated,

”I shall see that the laws are rigidly enforced in all respects and that good order prevail throughout our limits. I hope most earnestly that if there be any turbulent tendency anywhere it will be subdued, that passion will always be subordinated to reason, and that there will be no occasion to resort to harsh means to insure the public peace; but if riot or disorder should occur, whether in the crowded city or rural district, and the local authorities are unequal to the task of quickly suppressing it, no time will be lost by me, as the executive officer in using the power of the Commonwealth to restore the supremacy of the law, let it cost what it may, in blood and money.”

While the white-owned Alexandria Gazette omitted this part of O’Ferrall’s address in their coverage, the Black-owned Richmond Planet printed it, with further comment,

“This is a notice to lynchers that their days of bloodshed and revelry are at an end.” 9

Hope Fades

John Mitchell, Jr., editor of the Planet, took O’Ferrall at his word and believed Virginia’s African Americans had an antilynching champion in the new Governor. But this confidence waned as O’Ferrall moved mob law from the streets into the courtroom, aided in the effort by the General Assembly’s approval of the death sentence for the ambiguous, difficult-to-disprove charge of attempted assault.

In January 1894, the General Assembly amended Chapter 32 of the Code of Virginia, Sec. 3888, making any “attempt to commit rape” punishable with death, or confinement in the penitentiary for at least three and no more than 18 years. 10

Mitchell reacted with abject disappointment. No other state had a statute on the books making “attempted rape” even “more outrageous than murder!” They have given white people a “license to hang Negroes [sic],” he wrote.

Still, the editor’s hopefulness is easily read at other early moments in O’Ferrall’s reign. He praised the Governor for sending Alexandria’s Light Infantry, led by Capt. George Mushbach and considered the finest in Virginia, to Manassas in February and again in March to ensure two men accused of raping white women were not killed before they could stand trial.

At the same time, O’Ferrall responded to a petition signed by 400 white people for the pardon of James B. Richardson, one of the few men convicted of a felony at Roanoke, by reducing his sentence to 24 hours, time served.

Weeks later, Benjamin White’s mother showed up on Mitchell’s doorstep seeking help from him to get a pardon from the gallows for her boy and O’Ferrall met with her. He expressed great sympathy as the mother explained that the accuser consented to be with her son, but when locals threatened her, she gave in, as did her friend, and out of fear for their own safety they made the accusations. But, her truth did not move the Governor to act, and her son was hanged on April 28th, 1894. 11

Days later, on May 5, 1894, Mitchell gave credit to the Governor, praising him for once again calling in troops to protect a man called Lee from being lynched. But it soon became apparent O’Ferrall was not motivated by justice as much as he was appearances.12

As Black Virginians leaned with collective might toward a better future, every step forward pulled them further back.

The First Legal Lynching

The Court at Winchester sent Thornton Parker, a Black man, to the gallows for an attempted rape on April 19, 1895. Arrested on March 5 for allegedly assaulting a young married woman, officials had to move Parker multiple times to avoid lethal mobs. He was indicted six days later, on March 11, and his trial was held four days later, on March 15.

The night before his trial, three companies of militia were called to town, and white men bearing 122 guns “kept order” by parading through the streets. The next day, after a four-hour trial, the jury agreed that Parker “attempted to rape” the white woman. He was sentenced to death by hanging. 13

Richmond Planet’s Mitchell questioned the constitutionality of the newly applied rule,

“Is this the recognition of the constitutional provision which guarantees equality before the law? We shall never agree that it was right to sentence and hang Thornton Parker, charged with attempt to criminally assault a white lady…It is ridiculous to talk of making the punishment for the attempt to commit a crime the same as the punishment for the commission of the crime itself. Ask yourself, if Parker was a white man and attempted to criminally assault a white woman, would he have been sentenced to death? If Parker had been a white man and had attempted to criminally assault a colored woman, would he have been sentenced to death? If you answer all of these questions in the negative, or any one of them that way, then Parker should not be hanged…standing upon the threshold of the 20th [century], the legislature of Virginia takes a backward step and gladly makes the Virginian of African descent the victim. Human life is too precious to be thus sacrificed and paltry prejudices too fleeting to be thus pandered to.”

The Second Legal Lynching

On September 7, 1895, a mile from the border with Tennessee, Kit Leftwich (Leftridge), who was Black, was accused of raping a white girl, who was either 12, 13, or 14 years-old. He was arrested that same day and put on a train to avoid a gathering mob. The News and Advance wrote, “The authorities have promised to convene a special grand jury for his case, and say that the prospects are good for a legal termination of the case within 30 days.” (Emphasis added.)

Three days later, on Sept. 10, Leftwich was indicted. That night, 50 deputized white men guarded him overnight. As his trial unfolded the following day, a menacing mob congregated outside the courthouse. Leftwich was sentenced to hang.

On Sept. 12, the News and Advance wrote, “The trial and conviction [of Leftwich] are one of the speediest on record.”

That was, until Alexandria’s courts had the chance to try Hawkins later that month.

An Alexandria Farm Girl Upsot

Mary and Bessie Russell ran toward the sound of a girl screaming and found Sadie Sherrier, their neighbor, all alone, on the ground, her school books arrayed around her, an upside-down lunch basket nearby. They helped her up, dusted off her things, and walked home with her as the sun was setting in the October sky.

The Almost Lynching of Albert Hawkins

An hour or two later, Sadie’s brother-in-law George A. Conley banged on Daniel Madderson’s (or Matterson’s or Masterson’s) door in Lincolnville. Conley, British by birth, demanded that Madderson hand over his nephew, Albert Hawkins. He made a citizen’s arrest. 14

“Neither waiting nor caring for a warrant, [Conely] took him [Hawkins] into custody and marched him to the Sherrier farm. Several men who had heard of the assault joined Commelly [sic] on the way back, and thus the mob began to form.” 15

William H. Sherrier, Sadie’s father, was a first-generation American of German descent. He held large tracts of land on the Falls Church Road in the Washington District of Alexandria County. It was dark when Conely approached Sherrier’s home with Hawkins in his grip and Madderson in tow. Sadie was called to the porch and asked to identify her assailant. When she pointed at Hawkins, he panicked and started to run. Mr. Sherrier reached inside the doorway, grabbed a double-barreled shotgun, cracked it, snapped it, and leveled it at Hawkins,

“Halt, or I fire.”

The boy fell to his knees, denials pouring from him. “He pretends he never saw the little girl until brought into her presence and says he was sawing wood at the time the alleged assault was committed,” reported the Alexandria Gazette. 16

With his adult uncle beside him, Albert’s youth must have come into sharp focus, Sherrier released Hawkins from the gun's gaze and grabbed his coat. He led the crowd and their prisoner to Magistrate Hall, where they were turned away because they didn’t have “commitment papers,” according to the Washington Post. They then went to William Payne’s home, another Justice of the Peace, who lived nearby in Cherrydale.

“Mr. Payne, seeing the serious turn that the affair was taking, promptly appointed several of the more intrepid men in the crowd as deputy marshals and warned them that they would be held to account if they failed to assist his regular deputy, Massey. This took from the mob the men who might have been its leaders,” the Post reported.

Payne was a wealthy, politically connected, ex-confederate who had considerable landholdings near Memorial Bridge; he had been appointed to serve as Justice of the Peace earlier that year. A hearing was held in Payne’s kitchen that lasted two-to-three hours, the reason, a reporter conjectured, was: “a sort of desire on the part of all concerned that the mob should be given time to get a rope.” 17

Later, in retrospect, the Alexandria Gazette reported that the hours-long meeting was really an attempt to protect Hawkins from the growing mob outside.

Either way, at least 18 white men, farmers and neighbors of Sherriers, gathered outside Gen. Payne’s home. But so did Hawkins’ Uncle Madderson and nearly a dozen Black men from Lincolnville. Their presence was meant to thwart the would-be lynchers because the white men were well known and could be identified if they attempted to take the law into their own hands.

Inside, William Payne wrote up the father’s complaint, stating that Hawkins “violently and feloniously” assaulted and “attempted to carnally know” Saddie, a white girl, “between eleven and twelve years old.” The description of the alleged assault was vague in the charging documents. 18

“These are therefore to command you on the name of the Commonwealth of Virginia, forthwith to apprehend said Albert Hawkins and bring him before me or some other Justice of the said County to answer the said complaint and to be further dealt with according to the law.

Given under my hand this 28th day of October, 1895.

William H. Payne. J.P. “

Endorsed.

Served as within directed by arresting Albert Hawkins and bringing him before the Justice, Wm. H. Payne.

R.L. Massey, Special Officer.

Judgement.

Committed to Jail for the action of the Grand Jury.

William H. Payne, J.P.

With the paperwork in order, Constable Massey, Hawkins, and Deputies John Costello and Robert O’Neill slipped out the back door and into the woods.

Outside Payne’s home, the Black men outnumbered the white farmers. Their presence and protection of the boy drew ire; it “….was gall and wormwood to the white residents. Hawkins must be lynched, let bloodshed follow if necessary.” 19

When the white farmers finally went into Payne’s house, they learned Hawkins had been spirited away. They searched the nearby roads and woods while the Black men continued watching and at times pursuing the white mob to protect Hawkins.

Massey and his crew stayed hidden in the woods for hours until he figured the mob had given up. He then took a “circuitous route” to the Alexandria jail and deposited Hawkins at 1 a.m. to await the action of the grand jury.20

If It Bleeds It Leads

The alleged assault of Sadie Sherrier happened on Monday, Oct. 28, around 3 or 4:30 p.m., according to news accounts. The Constable brought Hawkins to Alexandria in the first hour of Tuesday, Oct. 29. The morning papers promised a swift trial first thing on Wednesday, Oct. 30, explaining, “It would have been taken up today [Tuesday] but for the fact that they wanted to finish up the Justice of the Peace cases then in hand.” 21

In contrast to the allegations made in the charging documents, the Washington Times printed a detailed description of the alleged attack in the morning papers. 22

“When Sadie reached that point in the road opposite where Hawkins lurked, he sprang from his place of concealment. She had gone, perhaps a few feet beyond the clump of bushes under which he crouched, so that when he sprang upon her, he came from behind. The little girl did not see him when he broke from his place of hiding. Once at her side, he quickly pinioned her arms behind her, and despite her screams for help, he dragged her into the bushes at the roadside. The little girl fought madly. The wretch did not succeed in accomplishing his purpose and the struggle continued for some minutes, during which the girl's clothes were torn and shredded.” – The Washington Morning Times

The other morning paper, the Washington Post printed a possible motive. In this version of the attack, the assailant first steps onto the road and asks Sadie, “Haven’t you something in your lunch basket for me?” and after she tells him no and begins to walk away at a fast clip, she trips, falls, and Hawkins catches her before she hits the ground. “She screamed with all her might. He tried to hold her mouth. He tore her clothing from her. He threatened to kill her.” 23

The Washington Times evening edition, called the Times Herald, co-opted the Post’s motive, reporting the following: “Little Sadie Sherrier was returning from school when the boy, who had concealed himself in a small clump of scrub pines, sprang out, and asked her what she had in her basket. She told him nothing, and he then became enraged and attempted to assault her. He threw her to the ground and tore her clothing and badly bruised her. She screamed and the two Russell children came up. This frightened the negro [sic] and he then ran away.”

The other afternoon papers, the Alexandria Gazette and the Evening Star were in agreement on the course of events. The Gazette repeated the Post’s version, but omitted the part where the alleged assailant asked for food. Instead, the story began with Hawkins jumping out from behind some bushes. Later, when covering Sadie’s testimony at the trial, the Gazette referred to the motive mentioned by other papers, stating that Hawkins “propounded to her an insolent question” before the attack.

The Times Herald, Washington Post, Alexandria Gazette, and Evening Star stated that the Russel sisters, also children, answered Sadie’s calls for help. Only the Washington Morning Times story, the first edition published stated that Sadie’s brother-in-law, George Conely, came to her rescue.

“Her screams brought upon the scene her brother-in-law, George Comley [sic], who happened to be passing down the road. He broke into the undergrowth and, in one glance, apprehended the situation. Hawkins fled and the little girl rushed into the arms of her protector. As soon as Comley could disengage himself from Sadie, he gave chase to the fleeing negro [sic]. Through woods and fields, the race between evildoer and avenger continued, Hawkins setting a hot pace, but Comley kept on, and by superior endurance, overtook his chase. He was held till the arrival of a special officer, and in the meantime he had been identified by the girl. Slowly the heinousness of his crime dawned upon him, and as he began to realize the serious consequences which might follow, his fear increased. The news of the assault spread rapidly through the counties roundabout, and neighbors soon gathered at the Scherier [sic] home. The excitement was intense. Lynch talk began to be heard on all sides.” 24

While all the newspapers published headlines and text about Hawkins' narrow escape from mob justice, the Washington Times morning and evening editions [Times Herald] took things to the next level, seemingly encouraging a mob to manifest. They predict Alexandrians would take Hawkins from the Jail and lynch him that evening.

The Washington Morning Times wrote, “While there is no likelihood that there will be any relaxation of the vigilance of the officers of the jail there are a great many who believe that the white men and the friends of the girl will do all possible to visit swift and condign punishment on the fiend who attempted the outrage.”

The evening edition’s [Times Herald] headline read: “In Danger of Lynching, Albert Hawkins May Be Strung Up Tonight at Alexandria,” and the text continued, “It is almost certain that some attempt will be made tonight to deal out summary justice to the ravisher. No one will say that the negro [sic] will be lynched, or that it has even been considered, but if indications count for anything, there will be an attempt made to get at him tonight. The turnkeys of the jail believe that to be true and have been drilled in sounding the alarm for the militia. If the inhabitants hear twenty-one taps on the town bell they may know that the citizens of the county have decided to avenge the attempted assault of the daughter of a fellow-citizen.”

Mayor Luther Thompson, the Gazette reporter, clearly had his public office in mind when he wrote, “The fact is this city never was more quiet… as all newspaper men were aware as they were making their rounds. It was especially so in the neighborhood of the jail.”

Thompson probably recruited his colleague at the Washington Post to join him in reporting that there was no talk of a lynching, since both papers ran headlines and stories that countered Tuesday’s reporting, including the Post’s own reporting.

“No Danger From A Mob; No Desire to Lynch Hawkins Expressed in Alexandria, Such Reports Have Been False” announced the Post story, no longer front page, instead it was buried on page eight.

Thompson was emphatic that the Washington newspapers had wildly exaggerated, opining,

“All Imagination – the sensational accounts of excitement in this city yesterday and last night over the alleged outrage committed by a negro boy named Hawkins in the county on Monday existed only in the brains of the reporters who wrote them up for some of the evening and morning papers of Washington. It is said that some of these enterprising journals had cuts prepared in advance of the lynching of the boy in this city, which they imagined was inevitable.”

It was just such “exaggerations” that drew the attention of prison reform advocate Clarissa Oats Keeler, who described herself as white, and Christian, and therefore duty-bound to speak out against injustice. Keeler wrote in the Richmond Planet that the Washington Times “determination to arouse its readers to a state of indignation” led her to go “immediately to Alexandria” to investigate what had really happened.

A Boy on Murderer’s Row

By the time Keeler sat down with Albert Hawkins in his cell at the Alexandria jail, a number of reporters had been given access to him. After interviewing Hawkins, the reporters established that he was from Washington, D.C., and he, or he and his mother, had been living with an Uncle in Virginia for two-to-three months. Hawkins told them he had been working near where the alleged incident happened earlier that day, chopping wood for Charles Miller, but he said he never saw the girl before she accused him.

Albert Hawkins, a ginger colored boy, was born to George and Phebe A. Hawkins [nee Parker] in Georgetown on Oct. 20, 1880, making him barely 15 when he was accused. Albert’s father, George, was born enslaved in Sandy Spring, Md. He was liberated when he was 7 years-old. After the Civil War, George and his five siblings grew up with their parents Albert and Sarah Hawkins in Georgetown. For a while, he was employed as a domestic, but after marrying Phebe, George took on work as a coachman. When Albert, their only son, was born, George was 32, and Phebe was 30 years-old and they lived at 21 Stoddard Street in Georgetown. 25

In the same Washington Times newspaper article titled, “Albert Hawkins May be Strung Up Tonight,” the reporter interviewing the youth in the jail cell states that Hawkins told him: “I was born at No. 2010 H. Street Northwest in Washington, and only left there about three months ago.” The address was for the George Washington Hospital, built in 1824, but it is not where Albert Hawkins was born. Hawkins was born with a midwife's assistance at their Georgetown home, according to birth records. The “there” in the statement likely refers to Washington and not the hospital indicating Hawkins had recently left the District to live in Virginia.

The Evening Star reporter said Albert was the only family member staying at his uncle's in Lincolnville, and had moved to Virginia just two months earlier. This is likely true because his mother was employed in Washington by a well known and respected criminal defense attorney. He may have gone to his Uncle’s for work or because her job was too demanding of her time and she thought he would be better cared for in Virginia.

But the Times reporter continued with another storyline: Albert said, “I was living at Holls Hill with my mother and uncle. My father has been dead about four months.

How did he die?” was asked.

He was shot in Bristol, Tenn., while running away out of jail.”

The Times report is most likely untrue. Phebe Hawkins died in 1898, and her death record indicates she was married (not widowed) at the time to George Hawkins. She was buried in a cemetery at his birthplace, Sandy Spring, Maryland. Also, no newspaper reports from Tennessee were found to verify this version of events. It is also worth noting, this information was reported by the same newspaper that the Alexandria Gazette accused of lying to try and incite a lynching. With this in mind, it's possible this report was made to criminalize Hawkins and justify mob violence against him.

The idea that Black people were inclined to criminal behavior was propagated during enslavement to stigmatize the Free Black population. Virginia had the second largest Free Black population among slave holding states, most of whom lived in the cities. In the 1830s, the state wanted to extend the vote to more white men, but they didn’t want to enfranchise Free Black men. Politicians engaged in a disinformation campaign to criminalize them. At the same time, the types of crimes people were sent to the penitentiary for expanded. Within 15 years, Free African Americans made up just six percent of the total population, but 40 percent of the states incarcerated. After emancipation, this practice grew, and by 1895, many crimes that were considered petty had been upgraded to felonies - it was even a crime to be homeless and/or unemployed. Also, Black youth, boys and girls, were not considered as innocent as white children by the dominant white culture.

The accounts of the reporters who interviewed Hawkins in his cell tended to adultify the youth. Hawkins was described as burly, “overgrown,” and looks like he’s 18-to-20 years old.

An article that appeared in a 2014 issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology explains that this continues today and, “Black boys can be misperceived as older than they actually are and prematurely perceived as responsible for their actions during a developmental period where their peers receive the beneficial assumption of childlike innocence.” 26

The Herald called Hawkins a miscreant and described him as “repulsive to look at.” While the language is archaic today, in 1895, miscreant would have messaged that Hawkins was vicious, depraved, villainous, and base.

The Washington Post called Hawkins “the very picture of ignorance, fright and despair,” adding he had “a small face and large eyes, which stood out with the awful fear that caused the fellow’s teeth to chatter and his voice to sink the the merest whisper. His tattered garments were very much too large for him, and his whole makeup seemed to be that of meanness and lowness.”

The book, Lynching in Virginia, identifies such a pattern in the white press, this way: “Reporters hiding behind their anonymity often contrasted the bestiality of the accused Black men with the innocent purity of the alleged white victims and the quiet determination of the mob, encouraging readers to identify with the lynchers and justify the revenge taken.” 27

Hawkins was literate, but the press described him as “cunning, street smart, hesitating, dull,” and of “low intelligence.” The Times reporter claimed the camera he carried into the cell scared Hawkins and complained the youth wouldn’t look the reporter in the eye when answering questions.

“In his story he contradicted himself several times, and while telling it kept his eyes riveted on the floor,” he reported.

But that would have been exactly how Southern culture demanded Hawkins respond to the white people interviewing him.

The Evening Star published a condemning sub-headline hours before the trial, “Albert Hawkins Partially Confesses to the Crime of Attempted Rape.” Jailor Timothy Hayes “told The Star reporter that the prisoner had made a partial confession to him.” Later, during the trial, Hayes would tell the courtroom Hawkins said, “did not hurt the girl much.”

Not surprisingly, The Times reported this information (likely provided by Hayes) in a more incriminating way, writing: “Whenever the door of the corridor leading to the cell is opened, the boy cries out: ‘hurt the girl much’...‘Don’t let them hang me’ He seems to think if he can be kept out of the mob's hands for a time, he will not be punished.”

Keeler’s experience meeting Albert Hawkins at the jail in Alexandria gave her a completely different impression than the press had been propounding. She was escorted down a corridor to a small, dark cell. When she saw Albert Hawkins, she said he looked like a child and seemed to have been neglected.

“The candor he showed when telling me he was innocent led me to think he might be telling the truth…I then determined to find out for myself.”

Keeler did not get the same impression from Hawkins' accusers.

Tuesday Evening

Alexandria County Court Judge Daniel McCarthy Chichester and the Commonwealth’s Attorney for Alexandria City Leonard Marbury told the press they planned to hold a grand jury on Wednesday morning. The court had already summoned a jury to be ready for a trial of Albert Hawkins immediately after a Grand Jury indictment. 28, 29

The Indictment of Albert Hawkins

On Wednesday, Oct. 30, at 10 a.m. less than 24 hours after Hawkins arrived in the dead of night on Tuesday morning, the Grand Jury assembled. The farm community that brought the case against Hawkins, knew Judge Chichester, a fellow farmer and land owner, well. Chichester had been a loyal and enthusiastic rebel, joining the Confederate infantry before the state even held a vote on whether to secede.

The Commonwealth was represented by Richard Johnson and Leonard Marbury. The Grand Jury was delayed as they waited for John Garrison to arrive, but when he did, they deliberated for just 15 minutes before returning with a True Bill. The Foreman, H.A. Whallon, read the Indictment:

“The jurors of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in and for the body of the County of Alexandria and now attending the said Court, upon their oath present that Albert Hawkins, on the 28th day of October, 1895, in the said County, in and upon one Sadie Sherrier, a female child of the age of twelve years, feloniously did, make an assault and her, the said Saddie Sherrier, by force and violence and against her will, feloniously did attempt unlawfully and feloniously to abuse and carnally know, by then and there, in the County aforesaid, throwing her down, pinioning her arms, tearing open her clothing, exposing her person and attempting to abuse and carnally know her, the said Sadie Sherrier, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Virginia.” 30

Their indictment added some details not seen in the charging documents, but some (not all) had been in The Washington Morning Times report, such as, “Once at her side, he quickly pinioned her arms behind her, and despite her screams for help, he dragged her into the bushes at the roadside. The little girl fought madly. The wretch did not succeed in accomplishing his purpose and the struggle continued for some minutes, during which the girl's clothes were torn and shredded.” The prosecution may have included more graphic incriminating details as part of their argument before the Grand Jury to buttress the charge of “attempted rape” that carried the death penalty. 31

They sent for Albert Hawkins.

Those who made up the jury that would sit for Hawkins' trial were mostly farmers and neighbors of Sherrier. They included Harvey Baily, William N. Febrey, John T. Birch, Thomas Peverill, E.B. Van Every, Frederick Hoenstine, John Duncan, George N. Pettitt, Walter L. Tucker, A.D. Torreyson, W.A. Schlevoigt and William S. Hall.

It is worth noting that Febrey, an active conservative Democrat, was a member of the Board of Supervisors for Alexandria County - the group responsible for paying the salary of Judge Chichester and Commonwealth Attorney Johnson. He was selected to be the jury’s foreman. 33

Moments Before the First Trial of Albert Hawkins

Clarissa Olds Keeler, 25 years old in 1895, would publish The Crime of Crimes or The Convict System Unmasked in 1907. The booklet exposed the discrepancies between the number of Black and white people sent to the penitentiary, especially among children. It also uncovered the extensive and profitable use of prisoner labor, deplorable prison conditions, and a myriad of abusive practices. Keeler arrived at the courthouse before the trial. She found the Russel girls and spoke with them privately, and that’s when they admitted to her:

“We don’t know anything about it, only what she [Sadie] told us. We came up the road and saw Sadie’s school books scattered around and the heels of somebody as he ran away, but nothing more.” And they “positively declared that Sadie’s clothing was not torn at all as had been told in the papers.”

Keeler then sat alone with Sadie for a bit and came away with the impression that a “boy, whoever he was, evidently wanted something to eat from her lunch basket as the first question he asked was for something to eat.” Keeler said Sadie told her nothing “to convince me that a criminal assault had been attempted upon her.”

She also spoke with George Conely, the brother-in-law of Sadie, who, according to the Washington Times, saved the girl from Hawkins. Conley told Keeler, “he was not there, neither did he know anything about it until afterward.”

Keeler accompanied the children into the courtroom and to the witness stand. She said their testimony was “substantially what they had told me.”

The Trial

Timothy Hayes led Hawkins to the bar.

“How do you plead?” asked Clerk of the Court Howard Young.

“Not guilty,” stated Hawkins.

The court assigned Murray Davis to be Hawkins' counsel. The young attorney had only qualified to apply for a law license in June 1894. Davis was the son of a prominent Alexandrian. He palled around with Evening Star reporter William Beckham, son of J.T. Beckham, the man elected mayor earlier that year, then resigned over the summer due to severe depression. The current mayor, Luther Thompson, was appointed by President of City Council Hubert Snowden, who was also Thompson’s boss at the Alexandria Gazette.

The jury was sworn in.

In his opening remarks, Marbury talked about the fairly new charge of attempt at rape that carried the death penalty, saying, “Such an atrocious and revolting offence demanded that speedy justice should be meted out…there was no crime of so revolting a nature and of such an atrocious character. It was so much so that the last legislature had made it punishable with death.” Marbury then “graphically depicted” the “facts of the case,” as he had laid out for the Grand Jury an hour earlier. 34

Although he had had no opportunity to meet with his client, it was now up to Davis to set the record straight. But instead, Davis waived the opening address for the defense.

The first witness was Sadie’s father, who swore out the complaint. “He said his little girl came home and told her mother of the assault. He also told of the chase and final capture of the prisoner. He took him [Hawkins] before his little daughter, who was positive that he was the one. He said the little girl’s clothing was torn from her and that her arms were terribly bruised by coming in contact with the underbrush during her struggles to free herself. His little daughter had told him that the boy threatened to kill her.”

Judge Chichester announced, “All boys under the age of 21 must leave. Bailiff, clear the room.”

A “pretty girl” with sable hair and eyes to match took the stand. Reporters said Sadie Sherrier looked much younger than her age. Then, in a “straightforward manner, she told how the prisoner, whom she positively recognized, had come up to her on the road, and said that he wanted to see her, and then seized and dragged her into the bushes. How she struggled and screamed. How her screams attracted the attention of the two Russell children, who came to her rescue, and the escape of the prisoner when he saw the two children coming toward her.”

Davis did not cross-examine the accuser.

Bessie and Mary Russel testified that they heard Sadie’s screams and when they reached her, “they saw the boy running away, but could not see his face as his back was toward them. They found some of Sadie’s clothing and picked up her school books and lunch basket. The books were scattered all over the place. They helped the girl to her home.” Another reporter noted that the girls “did not identify Hawkins.” 35

Davis did not cross examine the girls.

Hawkins' Uncle Daniel and Aunt Sarah Madderson took the oath and told the court that Albert had been at their home when the alleged attempted assault happened.

Keeler wrote, “The District Attorney and the lawyers showed the greatest possible bitterness toward the prisoner and were determined, as the boy had not been lynched at once, that he should hang. It was in vain that the boys' relatives, at whose house he had been living, testified that he was at home the hour the assault was alleged to have been committed.”

The previous day, Hawkins told two reporters who interviewed him in his cell that on the day in question he worked with Charles Miller sawing wood and grubbing stumps. They wrote in the newspapers that Hawkins was at Charles Miller’s place from noon to 5 p.m., adding that the property was close to the scene of the alleged crime. 36

Charles Miller wasn’t present at the trial, but his brother Thomas, “stated that the prisoner was about his place at 2:30 p.m. but left there a little later, and went in the direction where the assault was made. The boy was not about his place at 5 o’clock. He was positive of that,” according to the Alexandria Gazette.

The last to testify was Conely, who said only that “when the child came home crying, he managed to get from her a description of the negro [sic] who committed the assault. He then started on a search and found the prisoner.”

Albert Hawkins was not given an opportunity to defend himself. The jury, some of whom were likely to have been in the mob on Monday night, left the courtroom.

After a short deliberation, they returned. Phebe Hawkins wore a stoic mask as she stood beside her child holding a bundle of his clothes in her arms.

The gavel struck order, and Foreman Febrey pronounced, “We the jury find the prisoner, Albert Hawkins, guilty as indicted, and fix his punishment at death.”37

Albert turned to his mother and asked, “Why, mamma? I have done nothing to be hung for.” 38

One newspaper wrote, “While the jury was out yesterday, and it looked as if the full penalty of the law might not be imposed on Hawkins, threats of lynching were heard all over the courtroom, from men of prominence in the county, whom the testimony of little Sadie Sherrier in detailing the assault upon her had worked up to the highest pitch, and there is hardly any doubt but that these threats would have been made good had not the sentence of death been imposed.”

In the pages of the Gazette, Mayor Thompson shot back, “The fact is that no such scene took place, nor were any threats made. The tranquility of the courtroom at the time was noticeable.”

In the moments after the verdict was read and before Judge Chichester pronounced the sentence, Davis found his voice. In an attempt to prevent the judgment from being rendered, he interjected, “Your honor, we move that the court set aside the verdict and impose an arrest of judgment.” This is a rare plea, even in death penalty cases, and usually requires a serious flaw to be found in the indictment or trial. 39

The judge overruled Davis because, according to him, Hawkins had a fair trial. He then asked, “do you have anything to say or allege as to why the judgment of the court should not be pronounced against him?”

“No,” Council answered.

The judge picked up where he had left off, “thereupon it is considered by the court that Albert Hawkins be taken hence to the County Jail of this County, there to be safely kept, until the sixth day of December, 1895, and that on that day the Sheriff of this County, between the hours of Nine O’clock A.M. and 4 O’clock P.M. [sic] do take the said Albert Hawkins to the place of execution and there hang him by the neck until he be dead.” 40

Phebe Hawkins, who happened to be employed by “one of Washington’s best known criminal lawyers,” Campbell Carrington, implored the court for a new trial for her son.

Chichester explained he had just overruled a similar motion made by the defense counsel.

Albert was handcuffed and marched to the jail on St. Asaph Street, where in just six weeks, his execution would be held in the yard.

“No motion for a suspension of judgment was made in order that the case may be taken to the Court of Appeals, but it is believed it will be made later,” reported the Gazette. A suspension of judgment recognizes the conviction is true and was usually granted after a sentence had been announced. Invoking it would stay the sentence and often impose a new, less harsh one. Perhaps the Gazette was betting Carrington would get involved, or the Mayor was trying to assuage those who thought a death sentence was too much for an “attempt” to assault.

Keeler was shocked; she could not believe what she had witnessed, reflecting:

“What struck me most during the whole proceeding was the utter heartlessness and great bitterness shown by all concerned in the prosecution, from the judge down to the most ignorant juryman, and some evidently were ignorant indeed. I had been assured by one of Alexandria’s most prominent citizens that the boy would have an impartial trial, but I found it was the very reverse. I had not believed it possible that here, almost under the shadow of the nation’s Capital, such prejudice could exist against a prisoner because of his color.” 41

The Washington Post headline proclaimed, “Justice Was Swift Albert Hawkins Sentenced to Be Hanged Dec. 6, Indictment, Arraignment, Trial and Conviction Occupy Only a Few Hours.”

The Evening Star reporter was also struck by the pace of justice, writing, “This is one of the quickest trials ever taking place in this city, and the verdict meets with the approval of the citizens generally. The motion for a new trial was made and overruled by Judge Chichester.”

News of the verdict raced across the state, the Virginia Attorney General summoned Judge Chichester and Commonwealth Attorney Marbury to Richmond. On Oct. 31, they met with Gov. O’Ferrall, who was reportedly working on his December message to the General Assembly. He intended to include recommendations to stem lynchings as well as gambling that had become endemic in Alexandria County. In the speech, he suggested strengthening the law to eliminate mob violence by prioritizing speedy trials, liberal application of the death penalty, and significant penalties and fines for mob justice. His goal was to make lynchings “dangerous to the participants, and expensive to the communities in which they occur.” The result would be the legalization of the lynching of Black Virginians. 42, 43, 44

Reprieve

While events were unfolding in Alexandria, the Governor became embroiled in controversy for attempting to ensure the safety of three African American women convicted, dubiously, of murdering a white woman. During the summer, Gov. O’Ferrall had to send two companies of militia to Lunenburg, Va. to stop mobs from lynching them. After their guilty verdict, the women were sent to a jail in Richmond to await execution, but then the local judge said he found irregularities in the trial and wanted the women sent back to be retried. It was feared the women would be subject to mob justice upon their return.

On Saturday, Nov. 9, Gov. O’Ferrall was surrounded by advisors as they “poured over the law” to find a legal justification to keep the women in Richmond. After many hours without success, Gov. O’Ferrall directed his aide to “pick up the telephone and convey this order, “The prisoners will not be taken back to Lunenburg.” 45, 46

This set in motion a dramatic course of events and engendered statewide anger with the governor among whites, but won him friends among the African Americans.

“Governor O’Ferrall has the manhood to stand up and defy Judge Lynch and all the officers of his court, and has declared that his prisoners shall not be taken back to Lunenburg County, except under strong military guards,” wrote Mitchell, “Would that we had a Governor O’Ferrall in South Carolina and all the other Southern states; then lynch-law would soon be a thing of the past. All honor to Governor O’Ferrall of Virginia.” 47

The Virginia Court of Appeals found that O’Ferrall had acted beyond his authority in interfering with the judiciary, but they also provided the women with new trials. Charges were dropped against two of the women, and O’Ferrall pardoned the third.

Not So Fast…

The pronouncement of death for a 15 year-old boy after no due process and a sham trial did not sit well with the tightly knit African American communities of Washington and Alexandria. They rallied to Hawkins' cause and raised money to hire W.H. Sadler, a Black attorney and rising star, from Alexandria, to represent him.

On Tuesday, Oct. 29, while Hawkins was in a jail cell awaiting trial, Sadler and E.V. Davis, both young graduates of Howard Law, were making their debut at the Alexandria Courthouse. They were representing Thomas Bowman, charged with murder, against the same experienced prosecutorial team that Hawkins would face the next day - Johnson and Marbury.

“From far and near, men and women thronged and surged into the courtroom to witness the spectacle. For the first time in the history of that court, a colored lawyer’s voice was to be raised in eloquent tones for a brother’s legal rights,” mused the Washington Bee. 48

Marbury and Johnson wanted the maximum sentence - 18 years for murder. But the two Black lawyers thwarted their efforts, making a “profound impression upon the jury,” and winning a verdict of involuntary manslaughter for their client. Bowman, a Black man, was sentenced to just six months in prison!

“Their signal success in such a case against such well-trained attorneys presages for them a successful future,’ stated the Bee.

Once engaged for Hawkins, it did not take Sadler long to find a way to win the boy a new trial. Keeler said that “in their haste to dispatch the youth, they overstepped the bounds of the law.” Upon researching the case, Sadler couldn’t find a record of the prosecutor’s arguments to the grand jury or their indictment against Hawkins. Nothing was listed in the Minute Book - the official record of the County Court. If it wasn’t recorded, then there was no legal basis for the trial - the case would be considered “legally flawed,” invalid even, and the conviction could be overturned on an appeal.

On Nov. 11, Sadler appeared before Judge Charles Edgar Nicol, who was in his 20th year at the bar, and moved that a writ of error and supersedes be awarded to the judgment of the County Court and that a new trial be granted to Albert Hawkins because…

there was no record of any grand jury ever indicting him. 49

In a handwritten addendum to the court records, Clerk of the Court Howard Young, wrote, “upon an examination of the Minute Book of the County Court of Alexandria County, Virginia, it appears that there is a mistake in the foregoing record…The order of Wednesday, October 30th, 1895, stating that an indictment against Albert Hawkins for the attempt to commit rape is not on the Minute Book of said County Court and that there is no minute in said book of the guiding of said indictment in said case.” 50

His embarrassment almost seeps through the ink in each swirling cursive letter. The Post reported that the “new trial was a surprise in Alexandria, and Clerk Howard Young is criticized for not making the proper entry on the court record.”

After assessing Sadler’s argument, the court stated:

“The Court having heard the argument of Counsel therenow, and having maturely considered the said transcript of the whole record and the argument of crimes in said case, the Court finding from the said transcript of the whole record that there is no witness that the indictment for or against the prisoner was entered in the minutes book of the County Court of Alexandria County, it is considered by this Court, that because there is no indictment of record against the prisoner in the said minute book of Alexandria County that there is error in the said judgement of the County Court of Alexandria County Virginia sentencing the prisoner Albert Hawkins to be hanged, and therefore this court doth hereby reverse and amend the said judgement of the County Court of Alexandria County, and doth set aside the verdict of the jury found against the prisoner in the County Court of Alexandria County and doth remand this case to the County Court of Alexandria County for a new trial therein and for the proceedings according to law.” 51

Hawkins was reportedly “overjoyed” with the news of a new trial. 52

And there didn’t seem to be any fear that a mob would form at this point, as the Washington Morning Times stated, the people were ready to let the law take its course. 53

The New Indictment

On Monday, Nov. 25, a new Grand Jury met to consider the charges brought against Albert Hawkins. This time, the indictment differed from the first in a way that appears to try to further justify an “attempt” at a rape conviction.

The Oct. 30 indictment stated the facts of the case this way:

Sadie Sherrier, a female child of the age of twelve years, feloniously did, make an assault and her, the said Saddie Sherrier, by force and violence and against her will, feloniously did attempt unlawfully and feloniously to abuse and carnally know, by then and there, in the County aforesaid, throwing her down, pinioning her arms, tearing open her clothing, exposing her person and attempting to abuse and carnally know her, the said Sadie Sherrier.

On Nov. 25, Foreman George O. Wunder, a leading citizen in the County and active in Conservative Democrat circles, read the new indictment:

“The Jurors of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in and for the body of the County of Alexandria and now attending the said court, upon their oath present, that Albert Hawkins, on the 28th day of October 1895, in the said county, in and upon one Sadie Sherrier, a female child of the age of twelve years or more, feloniously and violently did make an assault and, then, and there, feloniously did attempt by force and violence and against her will, feloniously to ravish and carnally know her, the said Sadie Sherrier, by then and there, in the county aforesaid, throwing her down, dragging her into the bushes, pinioning her arms, lifting up her drawers, exposing her person and with his pants and his drawers unbuttoned and his, the said Albert Hawkins, person exposed, in the county aforesaid, on the day and year aforesaid, he, the said Albert Hawkins feloniously by force and violence and against her will, feloniously did attempt to ravish carnally know and abuse her, the said Sadie Sherrier against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

None of the salacious details such as Hawkins pulling away Sherrier's undergarments and exposing himself to her were included in the original indictment. It is very unlikely that witnesses testified to such in Hawkins first trial as the newspapers would have reported it. 54

Hawkins' new trial date was set for the following Saturday, Nov. 30, 1895.

Hit Replay

The trial drew Black and white people from Washington and the surrounding counties. Spectators crammed into the courtroom on Cameron Street as they had a month earlier to watch W.H. Sadler as he delivered Thomas Bowman from the noose. Anything could happen, Hawkins may even be exonerated.

Many in the Black community had invested in Hawkins' defense and were eager to see justice done. Besides Sadler, they hired Captain George Mushbach who had twice led the ALI to stop lynchings in Manassas that year. The white attorney who grew up in Alexandria was neck deep in conservative democrat politics. Mushbach was considered a “brilliant attorney” and was one of the most powerful and well connected Alexandrians. A member of City Council for years, as well as Virginia’s House and Senate, and Mushbach at one time served as Commonwealth’s Attorney for Alexandria County. In fact, Mushbach and the prosecutor, Leonard Marbury, knew each other very well. The two had recently returned from a statewide meeting of the Democratic Committee in Richmond. 55

The day before the trial it was reported, “The feeling against the boy is still very bitter, but it is now thought that he will not get the full penalty of the law, but will be sentenced to eighteen years in the penitentiary. Capt. George A. Mushbach has been retained by the friends of the boy to defend him.” It is interesting this was reported before the trial. Mushbach’s reputation was on the line, how would it look if Hawkins was served the death penalty again? But if the talented defense team succeeded in freeing Hawkins, it would damage Marbury, who had just been appointed by the Governor as a special counsel to take on gambling and lawlessness in the County. Sadler was a wild card the establishment had not anticipated when they quickly tried and sentenced Hawkins to death under the new attempt charge. 56

The trial opened when Judge Chichester entered the courtroom, but it would not end until the shade of evening settled over the building. Marbury moved to invalidate the indictment from October and replace it with Mondays so the trial could commence.

This time around, the jury selection was more contentious, a pool of 16 was reduced to 12, at least eight of whom had large land holdings in Alexandria County. One lone white Republican, B.F. Matthews from Jackson City [today’s Crystal City], was chosen to serve. 57

Hawkins' lawyer followed the prosecution’s opening address with an eloquent rebuttal that emphasized the facts of the case.

Witnesses for the prosecution included Sadie Sherrier and her father, the two Russel girls, Charles Miller instead of his brother Thomas, and George Conley.

“The testimony was about the same as at the last trial, though somewhat stronger against the boy,” reported the Alexandria Gazette, adding that Sadie “fully identified Hawkins.”

In reference to the testimony of one of the Russel girls, Keeler wrote, she was surprised “to hear the girl who had told me positively she knew nothing about it tell the court how the boy dragged Sadie into the bushes and added other evidence which she had previously confessed her ignorance of.”

On cross-examination, Sadler “obliged her to confess that she was not an eye witness.” Keeler had high praise for the young Black attorney’s range and talent in his aggressive and “unwearied” defense of Hawkins. Adjectives she contrasted with the “democratic politician who was coining money by his presence” who she said “was conspicuous for his silence.”

On Hawkins behalf, his Aunt and Uncle testified again that he was with them when the alleged offense happened. Richard Noyes and several other witnesses bolstered their claims.

When Albert Hawkins took the stand, he strongly denied having committed the alleged crime. He told the jury he left Charles Miller’s house at 2:30 and was home by 3 p.m. He stayed there until Conley, a citizen, arrested him at 5 p.m. He never wavered from these facts even under heavy cross-examination by the prosecution. 58

Keeler observed, “The boy’s testimony was straightforward from the first and no amount of cross-questioning could make him acknowledge that he was guilty.”

Then, Sadler said, “Your Honor, defense calls Sadie Sherrier to the stand.”

“Objection,” griped Johnson.

“Sustained,” Judge Chichester stated.

“Cross-examination elicited little that was new, but so strong was the argument of the defense that the prosecution seemed to be about to lose their case.” 59

To try and counter Hawkins and his family's unwavering testimony about the timeline, Marbury’s team had to rely on William Payne in whose kitchen Hawkins endured the hours-long interrogation; W.F. Carne, Jr., one of the reporters who interviewed Hawkins alone in his cell without counsel in October; and the jailer Timothy Hayes who had been keen to share with the press that Hawkins made a “partial confession to him.”

Commonwealth’s Attorney Johnson & Greene teamed up and delivered their closing arguments to the Jury. Arguments for the defense were made by Sadler.

Keeler complained about Mushbach. “Was he going to sacrifice any of his political influence for the sake of saving the life of a Negro [sic] boy? Not at all. Not one word did he say to that jury.” 60

Next, Commonwealth’s Attorney Marbury took the floor for a final argument then rested the prosecution at 4:30 p.m. The jury left to enter their deliberations.

It took the jury longer to come to their decision. When they returned to the courtroom Foreman E.D. Brown stated, “We, the jury, find Albert Hawkins guilty as he stands indicted and sentence him to eighteen years imprisonment in the penitentiary.”

Their written declaration was crossed out by Marbury who rephrased it for “legal purposes” to read, “We, the jury, find the prisoner, Albert Hawkins, guilty as indicted and fix his punishment at confinement in the penitentiary for the term of eighteen years–E.D. Brown, Foreman.” 61

Judge Chichester immediately passed the sentence and declared the jury to have been “very merciful.” 62

On Monday, Dec. 2, the Gazette reported that the jury had come to their new verdict after taking the young age of Hawkins into consideration. Adding, “There will be no appeal and Hawkins will be sent to Richmond this week. The action of the jury meets with general approval.”

When the trial ended, Keeler said she spoke with Phebe Hawkins who told her, “if he [her son] had anything to do with the affair, he probably asked for something to eat, and the girl replied by calling him “nigger, nigger,” [sic] which made him angry and a scuffle ensued. Then a little prompting helped it to be construed into an attempt at criminal assault.”

The Richmond Planet’s headline on Sat. Dec. 7, stated, “His Life Saved. Strong Probability that an Innocent Boy was Convicted – The Prosecution Breaks Down, but the Jury Renders an Unjust Verdict.

Keeler agreed, writing, “I shall ever believe that an innocent boy helped to make out the long list of youths sent to the Virginia penitentiary in 1895.”63

Hard Time for Albert Hawkins

It was cloudy and just warm enough not to snow on Tuesday, Dec. 10, 1895 when Albert Hawkins arrived in Richmond. All of the prisoners who entered the penitentiary that day were Black and he was by far the youngest. 64

Keeler wrote that too many Black children were going to prison, where they lived and worked with “hardened criminals” - was it worth destroying souls to make a profit for the state?

There were over 1600 convicts being held at the State Pen in 1895, 1200 of whom lived in 200 cells. They packed 20-30 prisoners inside each cell in the main prison. The majority of the population were Black. 65

An intake officer wrote in the register, Albert Hawkins; C; Attempted Rape; 18 years; Height 5’7”; Age 16; “dark ginger, same for hair and eyes”; MARKS: scars near his elbow, on his left shin near his knee, on his shoulder blade and on both feet, under his big toe. (They used scars to identify prisoners.) Discharge: July 29, 1911. Remarks: FARM. 66

There were about 200 prisoners living and working at the Farm in Goochland when Hawkins was assigned there. It could be considered a sort of reprieve from the old, notorious, deteriorating penitentiary where death stalked the crowded halls. In 1895, consumption, or TB, was responsible for half of all the deaths.

The newly established program that used prisoner labor was set up for inmates considered “miscreants and infirm.” The agribusiness included growing and harvesting grain, dairy and beef operations and a brick foundry. It sat on 4,000 acres that straddled the James River. The hard labor was thought to provide training and some sort of rehabilitation, but punishment and abuse was rampant. Hawkins was whipped multiple times, often for not working hard enough, according to punishment records from the time of his incarceration.

Barely two years after Hawkins entered the system, Phebe, his mother, became sick with TB; she died on June 16, 1898. She was just 48 years-old.

Years later, on a fair summer Saturday in 1911, Hawkins, 31, almost 32, left Richmond for Washington, D.C. For a while he lived with his father’s sister, Agnes Hogan in Georgetown near where he was born and raised. He left in 1918, when he was sent to South Carolina by the U.S. Military. He later returned to the District, lived on 18th Street and worked as a barber, but he never married or had a family of his own. On Feb. 19, 1829, after being hospitalized for more than two months, Albert Hawkins died of cancer. He was 47 years old. He is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the District. 67, 68

Conclusion

When Keeler came to Alexandria, she stayed for six days, visiting the neighborhood where the alleged attempted rape supposedly happened and she said, “In conclusion, I will say, one thing surprises me. It is that so little is done to ferret out the facts in cases such as I have presented. In the penitentiary according to the report for ‘95 fifty four colored men were serving sentence for attempt at rape and 36 for rape. How many except the Editor of the [Richmond] Planet have gone to any trouble to get at the real facts in these cases? Public sentiment says they are guilty and worthy of the severest penalty of the law. But how many of them, like this boy, may have been little, if at all, criminal in their conduct?” 69

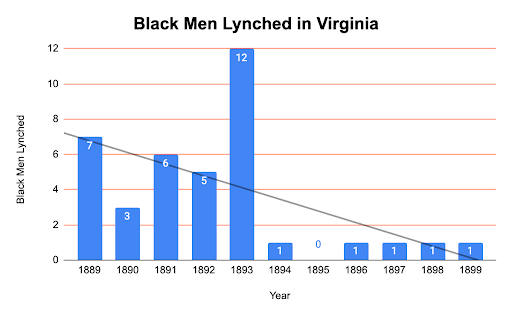

At least 70 Black people were lynched in Virginia from 1864-1899, according to the Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia project. The high water mark came in 1893 when 12 people were killed by mobs, one of those was Thomas Smith in Roanoke. O’Ferrall came into office on the first of 1894, by the end of summer, an international team was threatening to investigate the state’s lynchings as a result of Ida B. Wells’ campaign. Virginia’s reputation needed to be shored up. The legislature had handed localities a new tool to use to use an amorphous charge of attempted rape to impose the death penalty. In the Albert Hawkins case, Alexandria accelerated the law’s usefulness to stem potential mob violence by prioritizing his trial and sentencing. Although the prosecution ultimately failed to secure the death penalty, its initial success likely avoided a lynching. Weeks later, Gov. O’Ferrall made a bargain with the white population - stop illegal mob killings and in return the state will help localities act quickly to prosecute and execute offenders. Fail and communities should expect some hefty fines. His bid worked.

Caption: Developed with data from the Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia, James Madison University.

The chart shows that a downward trend in lynchings began after the General Assembly linked attempted rape to the death penalty in 1893. Then, when O’Ferrall came into office, he used the militias liberally to protect those accused of rape and attempted rape. He began to encourage communities to promise speedy justice which resulted in performative due process and sham trials where the mob was often on the jury or at the courthouse. Lynchings slowed significantly. Then in December of 1884, in his address to the legislature he asked for legislation in the 1885 session to impose fines on communities where lynchings occurred. Lynchings plummeted. In fact, mobs formed just four times after O’Ferralls initiatives were introduced, two of which happened in Alexandria when Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas were lynched in 1897 and 1899 respectively. At the same time, executions of Black men for rape or attempted rape increased significantly.

In “Uneven Justice” Hegg wrote, “The governor weaponized Virginia’s legal code,” adding, “Legal lynchings began in earnest during O’Ferrall’s governorship.”

From 1877 to 1932, 72 Black men received the death penalty upon such charges and in all but two of the cases the alleged victims were white. During the same time frame, no white men were executed for a charge of rape or attempted rape. By 1960, 93 Black souls had been executed in Virginia for raping or attempting to rape white women.70

“Virginia would continue to wield the criminal justice system as an instrument of racial terror long after the mobs dispersed and the lynching era came to an end. Justice was not colorblind,” said Hegg.

John Mitchell Jr. was correct, lawmakers had given white men a “license to hang Negroes [sic].”

Researched and written by Tiffany Danitz Pache, Coordinator, Alexandria Community Remembrance Project

Char McCargo Bah was consulted in an attempt to locate the Madderson’s and George Hawkins place, cause, and time of death.

End Notes

- “A more speedy southern custom of lynching would be a more effective deterrent,” Harold Snowden, wrote in the Alexandria Gazette, Feb. 13, 1895, p. 2, to describe the idea of quick trials with a death penalty as lynching itself was a poor deterrent for rape.

- Producers of their Time: The Snowden Family Part 1

Most historians who have written about the retrocession decision have focused on voting rights, Alexandria’s debt problem, and the treatment of local banks as the reasons for white townsmen’s support. More recently, Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon have placed the protection of slavery at the “heart of the campaign, which was led, both locally and in Congress, by men deeply invested in the slave economy and culture of the district and the South.” Southern Congressmen became passionate advocates for Alexandria in their all-out effort to stop abolitionists and preserve the slave trade. - Lynching in Virginia Racial Terror and Its Legacy, p. 176

- Another news account reported that someone in the mob fired upon the officials as others battered the door.

- Gov. McKinney was at the Worlds Fair in Chicago. He didn’t return for two weeks and managed to avoid remarking on events in Roanoke. But in December, when he addressed the legislature, he said what happened in Roanoke was a “fearful example of the dangers of mob law.” Meanwhile, pulpits across Virginia and out of state were preaching on the subject of the Roanoke lynching and resulting disorder.

- Alexandria Gazette, Sept. 21 and 27, 1893, p. 2

- Richmond Planet, Jan. 20, 1894 “The speeches made last Tuesday night are so excellent that we reproduce them elsewhere, feeling satisfied that lynch-law in this section is on the wane and that the day is not far distant when Virginia will be noted for the law-abiding character of its citizens, the purity in the administration of its laws and the observance of those great principles which ensure success and bring prosperity within our doors. Lynch law must go!,” Mitchell wrote.

- Lynching in Virginia, p. 140

- Gov. O’Ferrall gave his inaugural address on Jan. 1, 1894. The Richmond Planet was a weekly so it covered the speech in its Jan. 6, 1894 issue on p. 2. The Alexandria Gazette, appears to transcribe the entire speech in its coverage of Jan. 2, p. 2, but they left out the information about lynching. Because of this, this address is missing from November’s newsletter about Ida B. Wells impact. (Ex-confederate soldier and representative in the rebel legislature, Harold Snowden was responsible for writing and editing page 2 of the Alexandria Gazette at the time.)

- Acts and joint resolutions, amending the Constitution, of the General Assembly of the State of Virginia 1893-1894, p. 29; Hathitrust.org.

- Norfolk Virginian, p. 1 April 28.

Benjamin White was just 20 years old and his mother told the Planet’s editor that she went to see the two white women who accused the men of rape. These two women lived two miles from Manassas and were very poor and unknown in town. The young men were not guilty of criminal assault she said, the two women invited them in. Robinson, the other man who was accused knew the women and had cut wood for them in the past. He took Ben White “in order to have a good time.” The women didn’t say anything for several weeks after the evening. But the two men had promised them money and when they didn’t bring it them the told the story. “They said they did not intend to have anything done with the boys, but the white people said if they did not, they would have something done with them.” Richmond Planet April 21, 1894, p. 1

- Richmond Planet, Feb. 10, Feb. 28, 1894; Richmond Dispatch, Feb. 8 and Mar 6, 1894.

- At the same time that Thornton was tried for attempted assault, T.J. Penn, who was white, raped Lina Hanna, who was Black, yet he was acquitted, Richmond Planet, April 20, 1895, p. 2

- Washington Post Oct. 29, 1895; the papers spelled Daniel and Sarah’s last name as Masterson, Matterson and Madderson. After multiple attempts to locate the family through ancestry and city directories, I settled on using the spelling Madderson because the documents used that spelling. However, the documents misspelled other peoples names in them, so it was ultimately a toss-up.; Virginia law allowed(s) private white citizens to Conley, a private citizen, arrest private citizens who are Black. But, it would have been better in a legal sense had Conley, who was born in Great Britain, to have sworn out a warrant for Hawkins arrest. Citizen arrests in Virginia remain legal.

- Washington Post, Oct. 29, p. 1

- Alexandria Gazette, Tuesday 29

- Washington Post, Oct. 29, 1895, p. 1

- "Albert Hawkins, a negro, on the 28th day of October 1895, in said county, in and upon one Saddie Sherrier, a white girl between eleven and twelve years old. Then and there being violently and feloniously assaulted her and attempting to carnally to know her, the said Saddie Sherrier then and there violently and against her will by force against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth. These are therefore to command you in the name of the Commonwealth of Virginia forthwith to apprehend the said Albert Hawkins and bring him before me or some other Justice of the said County to answer the said complaint and to be further dealt with according to law given under my hand this 28th day of October 1895

William H. Payne, JP"

Arlington County Circuit Ended Law Papers, 1870-1895, Box/Volume: b002, Accession: 54208, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. - Washington Post, Oct. 29, 1895, p. 1

- Ibid and Alexandria Gazette, Oct. 29,1895, p. 3

- A Grand Jury was held to investigate those acting as Justice of the Peace in Alexandria. There was suspected collusion between gambling entities and some of the Justices. William Payne and Mayor Luther Thomas were among those investigated by the Grand Jury. More information can be found in the Times Herald, Oct. 31, 1895, p. 3

- Times Herald, Oct. 29, 1899, pp. 1, 2

- The Washington Post was a daily paper that came out in the morning, the Washington Times was a twice daily paper with a morning and evening edition. The two other newspapers the Alexandria Gazette and the Washington Evening Star were published in the evening.

- The Washington Morning Times, Oct. 29, 1895, p. 1

- Year: 1870; Census Place: Georgetown, Washington, District of Columbia; Roll: M593_127; Page: 585B;1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.; The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Records of the U.S. District For the District of Columbia Relating to Slaves, 1851-1863; Record Group Title: Records of Districts of the United States, 1685 - 2009; Record Group Number: 21; Series Number: M433; Microfilm Roll: 2; Year: 1880; Census Place: Georgetown, Washington, District of Columbia, District of Columbia; Roll: 121; Page: 32d; Enumeration District: 012; Washington, District of Columbia, U.S., Birth Certificates, 1874-1895 [database on-line].