ACRP Newsletter (September 2025)

september 2025 Edition

Welcome to the September newsletter for the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project. This month’s feature article dives into a story about another divisive time in America and takes approximately 25 minutes to read. We have some pretty exciting news and upcoming events, so please feel free to skip past the story and come back to it when you have time to enjoy it.

History Rhymes…A lot

On the anniversary of the execution of the violent abolitionist John Brown, Americans were deeply divided on the question of slavery, and the recent election of a Republican, Abraham Lincoln, to the Presidency. It was December 1860.

Soon after Lincoln’s surprise win, South Carolina’s lawmakers made clear their intention to leave the Union. Lincoln was elected without the support of a single proslavery state, and while editorialists condemned South Carolina for toying with anarchy, there were a growing number of states mulling secession.

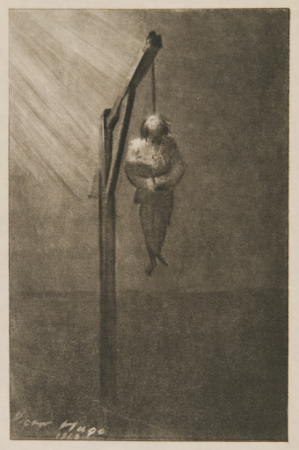

In this charged atmosphere, a Boston antislavery group invited a slate of speakers, with national reputations, to address the public on the question, “How Can American Slavery Be Abolished?” It was scheduled one year after the uncompromising Brown, who was white, was executed for leading a deadly raid in Harper’s Ferry, then-Virginia, in an attempt to ignite an armed rebellion to end slavery. The advertisement for the evening stated the intention was not to eulogize Brown, but to consider the ”great question of our age” because it would be the “most appropriate commemoration of his glorious death.” (Note 1)

Some Timely Perspective

As has been said many times in many contexts, including the American Revolution, one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter. After Brown was sentenced to death, Henry David Thoreau gave a speech in October 1859, A Plea for Captain John Brown, in which he described Northern sentiment as well as his own.

Right after the raid, there was a rumor Brown had been killed during it, and Thoreau said in that moment he heard “one of my townsmen observed that ‘he died as the fool dieth,” while another, “said, disparagingly, that ‘he threw his life away, because he resisted the government.’”

Thoreau said he didn’t like how American newspaper writers portrayed John Brown, a man who faced death for a cause in which Thoreau and many white and Black people, North and South, American and European, believed.

“The newspapers seem to ignore, or perhaps are really ignorant of the fact, that there are at least as many as two or three individuals to a town throughout the North who think much as the present speaker does about him [Brown] and his enterprise [Harpers Ferry Affair]. I do not hesitate to say that they are an important and growing party.”

Thoreau admitted his respect for his fellow men was fraying. “Our foes are in our midst and all about us. There is hardly a house but is divided against itself, for our foe is the all but universal woodenness of both head and heart, the want of vitality in man, which is the effect of our vice; and hence are begotten fear, superstition, bigotry, persecution, and slavery of all kinds. We are mere figureheads upon a hulk, with livers in the place of hearts. The curse is the worship of idols, which at length changes the worshipper into a stone image himself; and the New-Englander is just as much an idolater as the Hindoo [sic]. This man [Brown] was an exception, for he did not set up even a political graven image between him and his God.”

Thoreau warned that Brown’s message would live on despite southern attempts to paint him as a lone, maniacal crusader, and the raid as a one-off instance.

Within the year, Union soldiers gave voice to Thoreau’s prediction, singing John Brown’s Song, as they marched and gathered in camps. Abolitionist and poet Julia Ward Howe took up their ballad, replaced Brown’s name with that of Christ, tied the North’s cause to ending slavery and the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” transformed the Civil War into a holy crusade.

But in the time before the war, when Thoreau was delivering his speech, most of the country benefited in some way from slavery’s contribution to the GDP. Not surprisingly, there were plenty of northerners who believed it wasn’t their place to interfere with the South’s “peculiar institution.”

The 1860 Republican Party platform didn’t advocate for the eradication of slavery. But it did protest its expansion into the territories. Lincoln distanced himself and the party from Brown and called out Democrats falsely blaming Republicans for Brown’s actions to try and win elections.

In fact, northern merchants and traders felt completely comfortable seizing upon the “Harpers Ferry Affair," to organize rallies in major port cities to denounce Brown and all antislavery advocates. They called themselves “Union Men” because the majority were involved with the Constitutional Unionists, a political party that avoided the slavery question and supported the status quo. In the 1860 election, Democrats were split north and south, with slavery moderate Steven Douglas representing northern Dems and proslavery John Breckenridge leading the southern faction. Virginia was one of three states to support the Constitutional Unionist John Bell, and with the Democrats split, the Republicans won the White House.

Boston, Monday, Dec. 3, 1860

When people gathered at Tremont Temple in Boston on a mild December day to hear a slate of speakers, including John Brown, Jr., Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass, address the question of abolitionism on the anniversary of John Brown’s execution, they found more than 200 well-healed businessmen standing on top of cushioned seats in the auditorium. They were described “not as laboring men,” but as men of “property and standing.”

When organizers attempted to bring the meeting to order, the Union Men kicked the seats, banged their canes, guffawed, hooted, and hollered. There were between 80 and 100 police present, but by all accounts, they did not protect the abolitionists’ right to assemble in the hall (for which they had paid) but, instead, allowed the crowd to overcome the event.

The usurpers slyly hijacked the meeting by outvoting the abolitionists and installed one of their own in the chair presiding over the meeting. They proceeded to pass the following resolutions:

“Therefore, it is resolved,

That no virtuous and law-abiding citizen of this Commonwealth ought to countenance, sympathize, or hold communion with any man who believes that John Brown and his raiders and abettors in that nefarious enterprise were right, in any sense of that word.

That the present perilous juncture in our political affairs, in which our existence as a nation is imperilled, requires of every citizen who loves his country to come forward, and to express his sense of the value of the Union, alike important to the free labor of the North, the slave labor of the South, and to the interests of the commerce, manufacturers and agriculture of the world.

That we tender our brethren in Virginia our warmest thanks for the conservative spirit they have manifested, notwithstanding the impoverished and lawless attack made upon them by John Brown and his associates, acting, if not with the connivance, at least with the sympathy of a few fanatics from the Northern States, and that we hope they will still continue to aid in opposing the fanaticism which is even now attempting to subvert the Constitution and the Union.

That the people of this city have submitted too long in allowing irresponsible persons and political demagogues of every description to hold public meetings to disturb the public peace and misrepresent us abroad; they have become a nuisance, which, in self-defense, we are determined shall henceforward be summarily abated.” (Note 2)

As soon as the resolutions were approved, Frederick Douglass addressed the usurper in the chair, and because of the rules governing the meeting, the Chair was forced to give Douglass the floor. The Union Men tried to shout him down.

He stepped forward, and with his looming presence and deep preacher's voice, Douglass said, “This is one of the most impudent, barefaced, outrageous acts on free speech that I have ever witnessed in Boston or elsewhere.”

Rapid applause and chants of “Free speech, free speech!” rang out.

“I have served the same master that you are serving -,” Douglass charged, “the slaveholders.”

“No, no! We serve God….” the Union Men proclaimed, while others jeered and yelled at Douglass to sit down.

Douglass disagreed, “You are in the service of the slaveholders of the United States.” He shook off his coat, placed it on the back of the chair, looked up, and said,

“I know it is a hard time for you…”

They kicked the seats and pounded canes on the floor to drown out the speaker’s words. Douglass continued,

“The freedom of all mankind was written on the heart by the finger of God.”

Knowing he was talking to men whose party platform explicitly required adherents to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law, a deeply unpopular law in the North that was regularly disobeyed to provide escaped people sanctuary, Douglass continued,

“It is said that the best way to abolish slavery is to obey the law. Shall we obey the bloodhounds of the law who do the dirty work of the slave catchers? If so, then you are fit for your work. Mr. Norris of New Hampshire asked Wade of Ohio, in the Senate of the United States, if he would render his personal assistance to the execution of the Fugitive Slave Law, and that noble-hearted man and Christian gentleman replied, promptly, ‘I will see you damned first.’”

“Time, Mr. Chairman, Time,” several called out.

“Mr. Douglass has exceeded his floor time,” said another.

Douglass directed his comments to them, “Sirs, there is a law which we are bound to obey, and the Abolitionists are most prompt to obey it. It is that law written in the Constitution of the United States, saying ‘all men are born free and equal,’ and that we include all colors, too.”

“The Indians also,” the usurper chairman asked Douglass.

“Yes, Indians; and also that every man has a right to the use of his own body - even the President of this meeting.”

To which the Union Men howled.

“They cast aside with indignation the wild and guilty fantasy that man owns property in man, even in that stout, big-fisted fellow down there who has just insulted me,” Douglass said.

Boos bellowed forth.

Rev. D.C. Eddy took the stage, according to accounts, he wasn’t an abolitionist, yet he denounced the behavior of the Union Men, calling their obtrusions “unworthy of those who fought for freedom of speech in ‘76.”

“I come upon this platform to look into the faces of men who, in the year 1860, and within sight of Bunker Hill, are willing to trample on free discussion. I want to ask the young men of Boston and the grey-haired merchants of Boston what they will gain by this procedure?” Eddy asked.

Fists flew. Whistles blew.

The police asked the women to leave for their safety, to which “those on the main floor all took seats. Those in the galleries looked daggers” at the men below. The women were “determined to resist to the last.” (Note 3)

The abolitionists made multiple attempts to take back their meeting.

At least one weapon was spotted, cries to “put all the n------ out” and to “blow them up!” filled the auditorium.

Although explicitly asked to protect the meeting, the Mayor of Boston gave orders to shut it down and close the hall. To which, Rev. J. Sella Martin announced the meeting would commence at Joy Street Baptist Church.

“Thus in Boston, the ‘Cradle of Liberty,” in the year 1860, with the protection of the authorities and at the institution of the traders, the right of free speech was trampled under foot by a mob, in a peaceful meeting, whose avowed object was to discuss the means of abolishing slavery!” responded the editors of The Liberator, Dec. 14, 1860, a weekly abolitionist newspaper.

Joy Street Baptist Church

A mob of thousands gathered outside the doors of the Black church, blocked from entering by 15 men in blue. The militia was on high alert, readied and awaiting orders to come to the aid of those in the meeting. Police throughout Boston donned armor in case they were called to intervene.

As the meeting moved venues, the audience grew, gaining supporters not to their cause but to free speech. People were outraged by the Union Men’s antics. A person identified by the initials GWS wrote in a letter to The Liberator, “To our great delight [the meeting] was so thronged by the defenders of free speech, that only with difficulty did we succeed in obtaining a standing place in the gallery.”

G.W.S. also observed that it was the Black community that provided refuge for American liberty that evening. “What a dispensation of fate, that former slaves should, by an asylum in their church, discharge their indebtedness to the very ones who provided them with an asylum in the free States!”

Following the time period’s formal rules for an assembled meeting, the audience elected Frank B. Sanborn to Chair. Speakers, including Wendell Phillips, Lydia Maria Childs, John Brown Jr., Frederick Douglass, Parker Pillsbury, and H.F. Doyles, then addressed the burning question, “How Can American Slavery Be Abolished?”

After which, resolutions on the right to assemble and express opinions were approved by those attending.

There were a few violent eruptions outside that left at least one policeman seriously injured and another person badly hurt. But the officers on site successfully kept the mob from entering and interfering with the meeting. When it concluded, newspapers reported that the mob only broke up to follow and harass attendees on their way home.

Free Speech in the News

Newspapermen took up the cause straight away and derided the Union Men who tried to choke debate. “In a government like this, all men, both as classes and individuals, have a right to the free expression of their honest opinion, and for every infringement of that right, the whole community must in the end suffer; for the same power which can suppress the expression of one class of opinions, can also be used for the suppression of other opinions, whether in the form of public speech, legislative enactment, or judicial decisions, which may not be in accordance with the prevailing sentiment of the hour,” Dedham Gazette.

The Following Sunday

Six days later, on Dec. 9, 1860, Frederick Douglass spoke to the 28th Congregational Society at Boston Music Hall. The audience was unusually large because, by all accounts, people wanted to hear more about what had happened at the Tremont Temple.

Douglass presented his scheduled lecture, “The Self-Made Man,” and upon its completion, the talented orator addressed the president of the meeting and asked if he might make some additional remarks.

After gaining permission, Douglass addressed those assembled in what has become known as “A Plea for Freedom of Speech in Boston."

“The world knows that, last Monday, a meeting assembled to discuss the question: “How shall Slavery be Abolished?”

The world also knows that that meeting was invaded, insulted, captured, by a mob of gentlemen, and thereafter broken up and dispersed by order of the Mayor, who refused to protect it, though called upon to do so. If this had been a mere outbreak of passion and prejudice among the baser sort, maddened by rum and hounded on by some wily politician to serve some immediate purpose—a mere exceptional affair—it might be allowed to rest with what has already been said. But the leaders of the mob were gentlemen. They were men who pride themselves upon their respect for law and order.

These gentlemen brought their respect for the law with them and proclaimed it loudly while in the very act of breaking the law.

Theirs was the law of slavery. The law of free speech and the law for the protection of public meetings they trampled underfoot, while they greatly magnified the law of slavery.

The scene was an instructive one. Men seldom see such a blending of the gentleman with the rowdy as was shown on that occasion. It proved that human nature is very much the same, whether in tarpaulin or broadcloth. Nevertheless, when gentlemen approach us in the character of lawless and abandoned loafers—assuming for the moment their manners and tempers—they have themselves to blame if they are estimated below their quality.

No right was deemed by the fathers of the Government more sacred than the right of speech. It was in their eyes, as in the eyes of all thoughtful men, the great moral renovator of society and government, Daniel Webster called it a home-bred right, a fireside privilege.

Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power. Thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers, founded in injustice and wrong, are sure to tremble if men are allowed to reason of righteousness, temperance, and of a judgment to come in their presence. Slavery cannot tolerate free speech. Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South. They will have none of it there, for they have the power. But shall it be so here? ‘Shall tongues be mute?”

Even here in Boston, and among the friends of freedom, we hear two voices—one denouncing the mob that broke up our meeting on Monday as a base and cowardly outrage, and another, deprecating and regretting the holding of such a meeting, by such men, at such a time! We are told that the meeting was ill-timed and the parties to it unwise.

Why, what is the matter with us? Are we going to palliate and excuse a palpable and flagrant outrage on the right of speech by implying that only a particular description of persons should exercise that right?

Are we, at such a time, when a great principle has been struck down, to quench the moral indignation which the deed excites, by casting reflections upon those in whose persons the outrage has been committed?

After all the arguments for liberty to which Boston has listened for more than a quarter of a century, has she yet to learn that the time to assert a right is the time when the right itself is called in question—and that the men of all others to assert it are the men to whom the right has been denied?

It would be no vindication of the right of speech to prove that certain gentlemen of great distinction, eminent for their learning and ability, are allowed to freely express their opinions on all subjects, including the subject of slavery. Such a vindication would need itself to be vindicated. It would add insult to injury. Not even an old fashion abolition meeting could vindicate that right in Boston just now.

There can be no right of speech where any man, however lifted up or however humble, however young or however old, is overawed by force and compelled to suppress his honest sentiments.

Equally clear is the right to hear. To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker. It is just as criminal to rob a man of his right to speak and hear as it would be to rob him of his money.

I have no doubt that Boston will vindicate this right. But in order to do so, there must be no concessions to the enemy. When a man is allowed to speak because he is rich and powerful, it aggravates the crime of denying the right to the poor and humble.

The principle must rest upon its own proper basis. And until the right is accorded to the humblest as freely as to the most exalted citizen, the Government of Boston is but an empty name, and its freedom a mockery.

A man’s [persons] right to speak does not depend upon where he was born or upon his color. The simple quality of manhood [humanity] is the solid basis of the right—and there let it rest forever.”

January 1, 1863

Frederick Douglass again joined white and Black abolitionists at Tremont Temple. It was the first day of 1863, and again there was “an immense assembly” of people gathered together - this time they did so not to consider how to end the practice of human enslavement, but in anticipation of the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Douglass wrote that they were filled with hope and fear as they waited, anxious that at the last moment, President Lincoln might back down. They heard lectures and attended sessions all day as they awaited the announcement. During one such speech, Douglass mused about the changes that had taken place in Boston since propertied men went to Tremont with "knives and pistols" to stop the discussion of slavery. Preceding that, the South had for decades forced a gag upon Congress so that those who sent petitions calling for an end to slavery were not heard, their signatures were nullified by Southern Congressmen. By halting any public discussion of slavery, Douglass argued, they made it impossible for “honest” people to “look slavery in the face.”

“The pulpit, the press, and the people had been bought by the South, and the people of the North had helped to plunge the South into the hell in which she is now writhing,” he added.

Perhaps the most instructive thing for us, that Douglass said that day, was on the importance of a free press and free speech as a check against official lies (and omissions), “We were now suffering, and had been for the past two years, from the opposition to the freedom of speech and the press, so as to enable the truth to prevail against error, and when error has taken up the sword to cut down truth, then it becomes necessary for truth to fight for the right.”

“We have had a period of darkness,” Douglass said, “but are now having the dawn of light, and are met today to celebrate it.”

End Notes:

1 Boston Transcript, Sat. Dec. 1, 1860 ,p.3.

2 The Liberator, Fri. Dec. 7, 1860, p. 3; See also, Boston Evening Transcript, Mon. Dec. 3, p. 2.

3 The Liberator, Dec. 7, 1860, p. 3

4 Ibid. See also, Boston Evening Transcript, Tues. Dec. 4, p. 4 and Boston Evening Transcript Dec. 8 and Dec. 10, 1860; The Liberator, Fri. Dec. 14, 21 and 28, 1860, and Emancipation at the Dawn of Light.

In the News

Student Free Speech Upheld by Federal Judge

When the Shenandoah School Board restored Stonewall Jackson’s name to its high school, it violated the First Amendment rights of the students by forcing them to promote a positive image of a rebel general, a judge ruled. The case was filed in June 2024 by the Virginia NAACP and five students. In it, they allege the school board’s decision to reverse course and rename the school in honor of the controversial Civil War era figure violated the U.S. Constitution, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Equal Educational Opportunity Act. Read the Virginia Mercury to learn more.

HBCUs Locked Down After High Profile Assassination

The day after conservative speaker Charlie Kirk was assassinated on a college campus in Utah, and while a manhunt for his killer was underway, multiple Black Colleges were threatened, sending students and faculty into lockdown. While law enforcement has not established a link between the shooting of the white social media influencer and the threats to the historically Black colleges, Sam Barnett, a sophomore at Alabama State, said she and other students believe they are a byproduct of Kirk’s death.

“HBCUs getting threats after a white nationalist was killed is very on the nose,” Barnett told The Hilltop.

A national racial justice organization wrote on social media, “The last few days in this country have been filled with violence and tragedy. Our political landscape has become rife with rage, grief, and uncertainty. But what remains consistent is that Black people are the first targets during political unrest. Even when the perpetrators of political violence are unknown, our communities bear the consequence.”

Dr. Makola M. Abdullah, the President of Virginia State University, one of the threatened HBCUs, told students and faculty in a letter, “Let us be clear: these threats are not random. They are targeted attacks on institutions that have long stood as pillars of excellence, empowerment, and progress. HBCUs exist because we refused to be denied an education – and we thrive because we continue to rise in the face of adversity. To those who seek to silence or scare us: we will not be intimidated. For over a century, Virginia State University and other HBCUs have stood as a beacon of knowledge, excellence, and resilience. Today’s events only reaffirm our commitment to providing a safe and empowering environment for our students, faculty, and staff. The greatest revenge is to get an education. Every step you take forward, every class you attend, and every degree you earn is an act of resistance and triumph.”

Read more about the lockdowns from the Associated Press, The Guardian, or The Hilltop.

Alexandria Unveils Historic Marker for Colored Rosemont

On September 13, the African American History Division of the Office of Historic Alexandria unveiled a historic marker at the intersection of Wythe and West Streets that honors Colored Rosemont, a once thriving African American neighborhood that became the victim of discriminatory housing policies. Read more at ALXNOW, The Zebra, WTOP, and the Old Town Crier.

Curating and Connecting the Stories Behind the 1939 Library Sit-Ins

Learn more about ACRP co-chair Audrey Davis in an interview by ACRP’s Lisa Guernsey for New America.

Reflections on His Pilgrimage to EJI

Rev. Dr. Howard John Wesley, who heads up Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, recently returned from visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. He told his congregants the place makes you “wrestle with the mortality, brutality, impact and legacy of racial violence in the U.S.,” adding it was opened in 2018 amidst “an era when white guilt seeks to deny and downplay the horrific history of racism in America.”

Rev. Wesley continued, “I want to remind you of the importance of museums and memorials as places that hold historical truth. Historical truth is the only accurate compass to guide us into a better tomorrow than yesterday.

Historical truths are the northern stars that help us navigate our way out of repetition of our evil past.

Historical Truths are the lenses through which we can look at ourselves in the national mirror and fix the inequalities of our time.

Historical truths are the voices that call to us to remind us how far we have come as a people and how far we still have yet to go.

And as difficult as some of these historical truths may be for white people to ingest, it is only through confrontation and reflection that healing can come.”

The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project agrees. When we know the entirety of our shared history, it acts as an anchor for our community in divisive times.

That is why we are offering Alexandria City High School students the opportunity to learn our Black history from 1749 through the 1970s.

And it is why we are launching a research team to provide a full accounting of events that happened in this city from the end of the War of Rebellion through the imposition of the 1902 Constitution.

It is also why we hope people will participate in the Tables of Conscience book-themed dinner parties that provide an opportunity to discuss important issues and history while raising money for scholarships named after Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas.

As Rev. Wesley said, “If you never acknowledge the pain, you will never see the legacy, and you will never have a responsibility to heal what you damaged.”

Help ACRP Share Our Whole History With ACHS Students

We are still in need of funds for the Banned Truth Tour for our high school students. Please consider donating - learn more and donate on our campaign page.

Tables of Conscience Dinners

The Tables of Conscience book-themed dinners are back, and this time, the books featured are from a list of books banned by the government! Join us in an act of noncooperation while supporting Alexandria’s Memorial Scholarship Program that honors the lives of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, who were lynched in this city in 1897 and 1899, respectively. Tickets cost $125 per person, and each of this Fall’s dinners can accommodate up to eight guests.

Please pick a book you want to read and reserve a space to attend the dinner before they are booked up. The location of the dinner is revealed along with the host a week before the dinner.

The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Dubois

Sunday, Oct. 12

6-9 p.m.

8 tickets (only 6 left!)

Take the opportunity to read W.E.B. Du Bois ' collection of essays that expose the insidious magnitude of racism in American society. The work is a cornerstone of African American literature that helps readers better understand the Black experience after Emancipation and during Jim Crow. Dubois published his insights in 1903, yet they remain relevant today, as does his vision for a better future.

Reserve a space here for free, then pay $125 per ticket by donating on our campaign page with the Scholarship Fund of Alexandria.

A Long Time Coming: Reckoning with Race in America, Michael Eric Dyson

Friday, Nov. 14

6-9 p.m.

8 Tickets Available

The Department of Defense was so concerned about Americans finally starting to grapple with racism that they banned Michael Eric Dyson’s book, Long Time Coming. In a collection of letters written to recent victims of racial violence: Elijah McClain, Emmett Till, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, Hadiya Pendleton, Sandra Bland, and the Rev. Clementa Pinckney, Dyson exposed the anti-Blackness that infiltrates our culture, feeds police violence and injustice. The award-winning author, a professor at Georgetown University and an ordained Baptist minister, shares a way toward healing by the end of the book. The Equal Justice Initiative’s Bryan Stevenson has called the book both formidable and compelling, with “much to offer on our nation’s crucial need for racial reckoning and the way forward.

Reserve a space here for free, then pay $125 per ticket by donating on our campaign page with the Scholarship Fund of Alexandria.

Committee Meeting Reports

The Steering Committee of the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project met on Sept. 10 and reviewed the Benjamin Thomas Remembrance event, discussed the Banned Truth Tour and fundraising for the Remembrance Students, received updates for the launch of the Committee of Inquiry, Tables of Conscience Updates, and discussed plans for the Faith Initiative’s “Better Together” workshop with Braver Angels.

The Faith Initiative of the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project held a clergy coffee on Sept. 10 and a workshop on the afternoon of Sept. 17, 2025. The workshop was focused on ways to communicate beyond divisions within congregations, denominations, and across the community.

The Alexandria Community Remembrance Students were recruited at a club fair on Sept. 5 and had their initial introductory meeting on Sept. 19, where they reviewed ACRP’s documentary Resolved: Never Again and learned more about the Banned Truth Tour.

Upcoming Meetings

Applicants for the volunteer research positions with the Committee of Inquiry who have not yet participated in the OHA Volunteer Virtual Session can sign up to join on Sept. 29 or Oct. 3.

The next Clergy Coffee will be on Oct. 1 at 9 a.m. at Alexandria’s Black History Museum. Please stop by between 9 and 10:30 to meet other clergy and join the conversation.

The Steering Committee will next meet on Nov. 12 at 5:30 at Alexandria’s Black History Museum.

Alexandria Community Remembrance Project

The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project (ACRP) is a city-wide initiative dedicated to helping Alexandria understand its history of racial terror hate crimes and to work toward creating a welcoming community bound by equity and inclusion.

In Memoriam

Write "ACRP" in Comments on the donation form.

Office of Historic Alexandria

City of Alexandria, Virginia

ACRP@alexandriava.gov