How Ida B. Wells Exposed a Lie and Challenged the South

How Ida B. Wells Exposed a Lie and Challenged the South

It had been a generation since the Civil War ended, Black Americans were being killed by gangs of white men ever more frequently, and no one, not even the “best class” of Black people, were doing or even saying anything to stop the scourge, until one woman stood up and spoke up.

Armed with nothing more than the First Amendment, a petite school teacher turned reporter refused to back down, although her livelihood was destroyed, her savings lost, and her life threatened. She continued to speak out despite withering criticisms at home and abroad, and in spite of being called divisive, a liar, and vile. Nothing deterred Ida B. Wells from drawing the attention of the world to the South’s shameful fib. 1

The press and pulpit were silenced by the lie, abandoning an entire people who were systematically othered and criminalized by civil authorities.

“The Christian world feels that while lynching is a crime, and lawlessness and anarchy the certain precursors of a nation's fall, it can not by word or deed, extend sympathy or help to a race of outlaws, who might mistake their plea for justice and deem it an excuse for their continued wrongs,” Wells said.

As a Black, single, disenfranchised, southern woman, Wells should have been easily dismissed and discredited. But she persistently spoke the truth, and when America wouldn’t listen, she took her message overseas. Wells' campaign began in 1892, and by the end of 1894, every Confederate Governor felt the need to respond to her charges, including Virginia’s Gov. Charles Triplett O’Ferrall, who was head of the state when Joseph McCoy was lynched in Alexandria.

They Commandeered the Government and Shut Down All Opposition

Since the end of the Civil War, conservative southerners refused to give Black people the rights accorded to citizens. As the newly amended Constitution guaranteed these rights, they had to be underhanded about it. So, they employed fear, violence, and death to terrorize Black residents into quietly accepting an unequal status.

To cover up the violence, they invented stories first of criminal behavior and “rioting” that required Southern officials to aggressively impose law and order. But over time, it became harder to convince the rest of the states that with conservatives back in charge, these frequent “emergencies” continued unabated. So they began to use an unquestionable justification for mob violence… the rape of white women and children.2

Nothing could have 'hit upon' or been 'better calculated to accomplish its brutal purpose,” said Frederick Douglass, adding, the charge of rape against Black men marked them with the most “shocking” crime a man can commit. “All pity, fair play, and mercy” were instantly driven away.

The intention, he said, was to destroy the Black man’s character and make him unworthy of citizenship…unworthy to vote in elections. “It is a crime that places him outside of the pale of the law, and settles upon his shoulders a mantle of wrath and fire that blisters and burns into his very soul,” said Douglass.

The charge of rape became synonymous with lynching. It was made with unanimity. It was repeated. It was drummed into the public conscience. It isolated Black people and destroyed relationships.

“It has heated his enemies,” Douglass stated, and “deceived his friends at the North and many good friends at the South, for nearly all of them, in some measure, have accepted this charge against the Negro as true. Its perpetual reiteration in our newspapers and magazines has led men and women to regard him with averted eyes, dark suspicion, and increasing hate.”

The white press of the day, undaunted by facts, sensationalized stories of rape, egged on the mob to action, and dramatized every detail of the hunt and kill to the members of the mob, who in turn bought their papers to read about their imposition of their “righteous indignation.”

No preacher, white or Black, even if they believed a lynching victim innocent, felt that they could speak out against what was happening. If they dared to, the condemnation would be swift and, if the pastor was Black, could be deadly.

“Press, platform and pulpit are generally either silent or they openly apologise [sic] for the mob and its deeds. The mobocratic murderers are not only permitted to go free, untried and unpunished, but are lauded and applauded as honourable [sic] men and good citizens, the high-minded guardians of Southern virtue,” Douglass stated.

White officials in former confederate states had purposefully engaged in a 30-year campaign to criminalize Black people, to steal their labor with chain gangs, and take away their ballot. After decades, the message had sunk in and empowered the charge of rape, loaded as it was with Biblical condemnation, and gagged any opposition. Who dared question the charge of rape or stand up for someone accused of such an immoral, unacceptable act? Who would dare to make a woman face her accuser after experiencing such terror? With the press as their tool, the thunderous strike of type stole the voice of an entire people and any who might attempt to help them.

“This cry has had its effect; it has closed the heart, stifled the conscience, warped the judgment, and hushed the voice of press and pulpit on the subject of lynch law throughout this ‘land of liberty,’ wrote Wells, adding, “Men who stand high in the esteem of the public for Christian character, for moral and physical courage, for devotion to the principles of equal and exact justice to all, and for great sagacity, stand as cowards who fear to open their mouths before this great outrage. They do not see that by their tacit encouragement, their silent acquiescence, the black shadow of lawlessness in the form of lynch law is spreading its wings over the whole country.”

The Catalyst

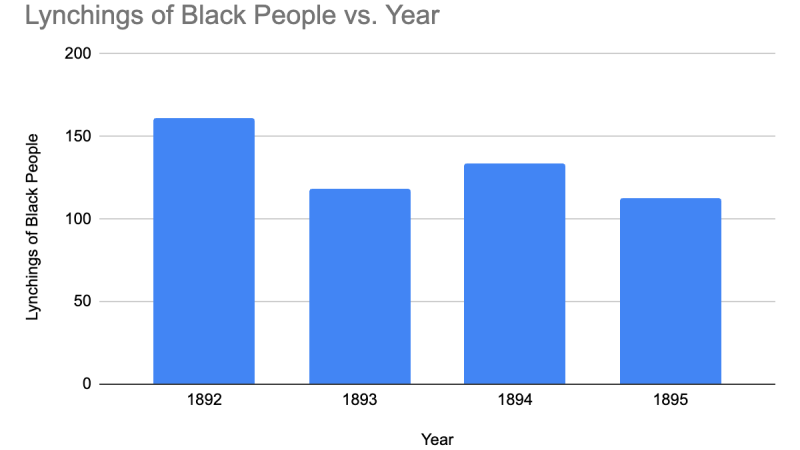

In 1883, at least 53 Black people were lynched. That same year, the Supreme Court nullified the 14th and 15th Amendments by defanging the two Civil Rights Acts (1866, 1875) meant to enforce them. Over the next decade, lynchings increased, peaking in 1892 when at least 161 Black people became victims of mob violence.3

That same year, a thriving Black community in Memphis, Tenn., Wells’ community, experienced its first lynching. On March 9, 1892, Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Lee Stewart were killed by a white mob. The three principles of a successful and growing co-op grocery in a mixed neighborhood that had been targeted by a rival businessman.

In her autobiography Crusade for Justice, Wells confesses she had come to accept the idea that lynchings, though extrajudicial and therefore wrong, were caused by rape. But when her friends were killed, despite any such charge, she began to question the premise.

“I then began an investigation of every lynching I read about,” Wells said.

The impact of Thomas’s death, in particular, was felt throughout the community. Wells wrote that he was upstanding, “a favorite with everybody; yet he was murdered with no more consideration than if he had been a dog…with the aid of the city and county authorities and the daily papers, that white grocer had indeed put an end to his rival Negro grocer as well as his business.”

Thousands packed up and moved from Memphis after the lynching, fearing that if someone as impeachable as Moss was so easily murdered, they could meet the same fate any time, any day. Wells used her columns in the Free Press to encourage migration to the irritation of the white businessmen.

The remaining Black community wanted to hold the lynchers and those who consented to the murders responsible. They boycotted the white owned businesses that were complicit. Some of the owners appealed to Wells, as co-owner of the Free Press, an African American newspaper, hoping she would encourage the community to return. Instead, Wells let her neighbors know they were having an effect.

The third week in May, the Free Press published a scathing editorial where Wells shared her findings that in each lynching that had happened since Memphis, no rape had occurred. “I stumbled on the amazing record that every case of rape reported in that three months became such only when it became public,” she wrote, attributing the mob violence to misinformation in some cases and, in others, the discovery of consensual relationships.

Her detractors used the editorial as a pretense to shut down Free Speech. In “defense of the virtue of white women,” Wells’ paper was overtaken and sold by creditors, just as had been done to Moss’ grocery after his death. The mob threatened to kill Wells if she returned to Memphis.4

Little did the prominent white citizens of Memphis realize, their actions would set off an International Antilynching Campaign that would force southern officials to answer to the injustice of mob law.

A Revelation

Editors of the prominent Black newspaper, the New York Age, invited Wells to tell her story. “Having lost my paper, had a price put on my life, and been made an exile from home for hinting at the truth, I felt that I owed it to myself and to my race to tell the whole truth now that I was where I could do so freely,” she wrote.

On June 25, 1892, a seven-column story titled Exiled, shared facts showing that rape was not the reason people were lynched, along with direct commentary from someone who had experienced racial terror.

According to University of Washington Professor Megan Ming Francis, “Never before had anyone questioned the veracity of lynching justifications with such authority. This was groundbreaking, since a majority of African Americans and whites accepted the mythologized explanation.”

After its publication, Frederick Douglass called it “a revelation.”5

Ten thousand copies were printed, 1,000 were sent to Memphis, and the rest spread across the country. Yet, the article did not gain traction in the white press.

Years later, in Crusade for Justice, Wells wrote, “Before leaving the South, I had often wondered at the silence of the North. I had concluded it was because they did not know the facts, and had accepted the southern white man’s reason for lynching and burning human beings in this nineteenth century of civilization. Although the Age was on the exchange list of many of the white periodicals of the North, none so far as I remember commented on the revelations I had made through its columns.”

Mary White Ovington, a white suffragette and future cofounder of the NAACP, said New Yorkers, by and large, believed the lie that made the victim indefensible and lynching excusable.

But the reaction in the Northern Black community was different; two New York women, Victoria Earle Matthews and Maritcha Lyons, were so moved by Exiled that they created a discussion group that met in church lecture halls. The number of people in the Black community who wanted to have ‘the conversation’ grew and grew. They invited Wells to speak to them and hoped they might raise enough money to publish her findings as a pamphlet that could be disseminated more widely.

“It resulted in the most brilliantly interesting affair of its kind ever attempted in these United States. The hall was crowded with them and their friends. The leading colored women of Boston and Philadelphia had been invited to join in this demonstration, and they came, a brilliant array,” Wells later wrote of the October 5, 1892, event that raised $500 and launched a “club movement” among Black women.

Before the end of the year, Exiled was updated and republished as Southern Horrors, Lynch Law In All Its Phases. It was written as “a contribution to the truth, an array of facts, the perusal of which it is hoped will stimulate this great American Republic to demand that justice be done though the heavens fall.”

In the foreword, Frederick Douglass wrote, “If the American conscience were only half alive, if the American church and clergy were only half christianized, if American moral sensibility were not hardened by persistent infliction of outrage and crime against colored people, a scream of horror, shame and indignation would rise to Heaven wherever your pamphlet shall be read.”

Southern Horrors shared eyewitness accounts from lynchings that bucked the common justification. The discrepancies illuminated a conspiracy of alternative facts. Statistics showed that of the 728 Afro-Americans lynched since 1881, only a third were alleged to have raped a white woman. Yet, the South had found a way to “shield itself behind the plausible screen of defending the honor of its women.”

Frustratingly, there seemed to be no way to fight back against the lie - Black Americans had been deprived of the vote and were not allowed to testify in civil court. The church and the press had been hoodwinked into silence, but the impact of lynching was already reaching beyond the Black community, according to Wells, who wrote:

“The result is a growing disregard of human life. Lynch law has spread its insidious influence till men in New York State, Pennsylvania, and on the free Western plains feel they can take the law in their own hands with impunity, especially where an Afro-American is concerned. The South is brutalized to a degree not realized by its own inhabitants, and the very foundation of government, law, and order are imperiled.”

Invitations Abound

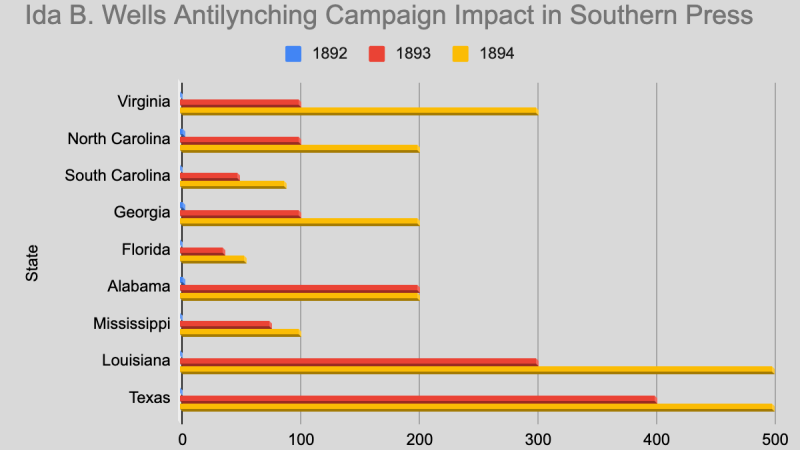

The October engagement in New York and the publication of Southern Horrors led to more invitations for Wells to speak. She toured cities in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.

In Boston, Wells began to rack up some meaningful successes. She addressed a white audience for the first time. At that time, William Lloyd Garrison (son and namesake of the famous abolitionist) told Wells he had refused to do business with a group in Memphis, and he shared with them that it was on account of how they mistreated Wells and the Black community. Another win - The Boston Transcript and Advertiser was the first New England white owned paper to report on Wells and her findings.

While promoting Southern Horror in homes, churches, and halls, Wells met British Quaker, Human Rights Activist, and Writer, Catherine Impey - this connection would soon lead her overseas.

A Door Opens

On Feb. 1, 1893, Henry Smith, 17, accused of raping a three-year-old white girl, was brutally tortured and burned to death at the county fair in Paris, Texas. 6

The incident was so disturbing that it traveled the Atlantic almost overnight. A Scottish woman read about it and contacted Impey, who told her about Wells' testimony. The two women began working to bring Wells to Britain to help them better understand what was happening in America.

“It seemed like an open door in a stone wall,” Wells wrote. “For nearly a year, I had been in the North, hoping to spread the truth and get moral support for my demand that those accused of crimes be given a fair trial and punishment by law instead of by mob.” She admitted that the white people in Boston were the only ones to give her a fair hearing. The white press, which she believed was the best way to reach those “who alone could mold public sentiment,” continued to ignore her.

She hoped the British, who lived in a powerful white nation, might unlock the door to white America and present an opportunity to sway public opinion. “In order to get the sympathy we so much needed, we had to go thousands of miles across the ocean,” Wells said.

Wells went armed with letters of introduction from Frederick Douglass, who toured Britain in the 1840s and successfully reinvigorated the then-dormant antislavery movement.

In recommending Wells, Douglass was careful to tell her white hosts she was not divisive, nor did she wish to provoke any hostilities. “She goes with the plain, simple, unvarnished truths which are too well known to the people of this land - truths which are shocking to the civilization of this age – and asks that a sentiment against such outrages be expressed and all other worthy means be exerted to make it possible to abolish lynchings.”

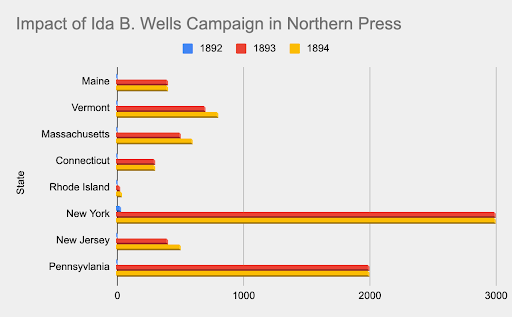

Throughout April and May of 1893, while speaking to small audiences in drawing rooms and church halls, Wells quickly learned the British had no idea what was happening in America. They thought that “Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation and Congress’s three amendments to that measure” had freed and brought equality to Black Americans.

They were surprised to learn that, although African Americans had pleaded with multiple Presidents and signed petitions by the thousands for Congress, nothing had changed.

She told them that “since 1876, the negro vote in the South has been nullified,” and because of gerrymandering, “one white vote there is equal to three colored [sic] ones.”

Wells effectively countered the lies about African Americans’ supposed criminality and lack of intelligence. Her very presence was a testament, disproving much of what the British had been led to believe; still, she used photographs from lynchings to support her arguments.

Her initial trip raised Awareness in Great Britain and in America’s white press - just not in the South.

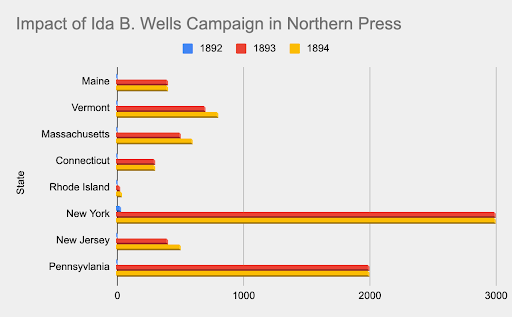

In 1892, when Wells published her initial findings regarding lynchings and spoke at countless meetings in the Northeast, there was little reported in “mainstream” or white newspapers. But this changed significantly in 1893 and continued in 1894 and beyond.

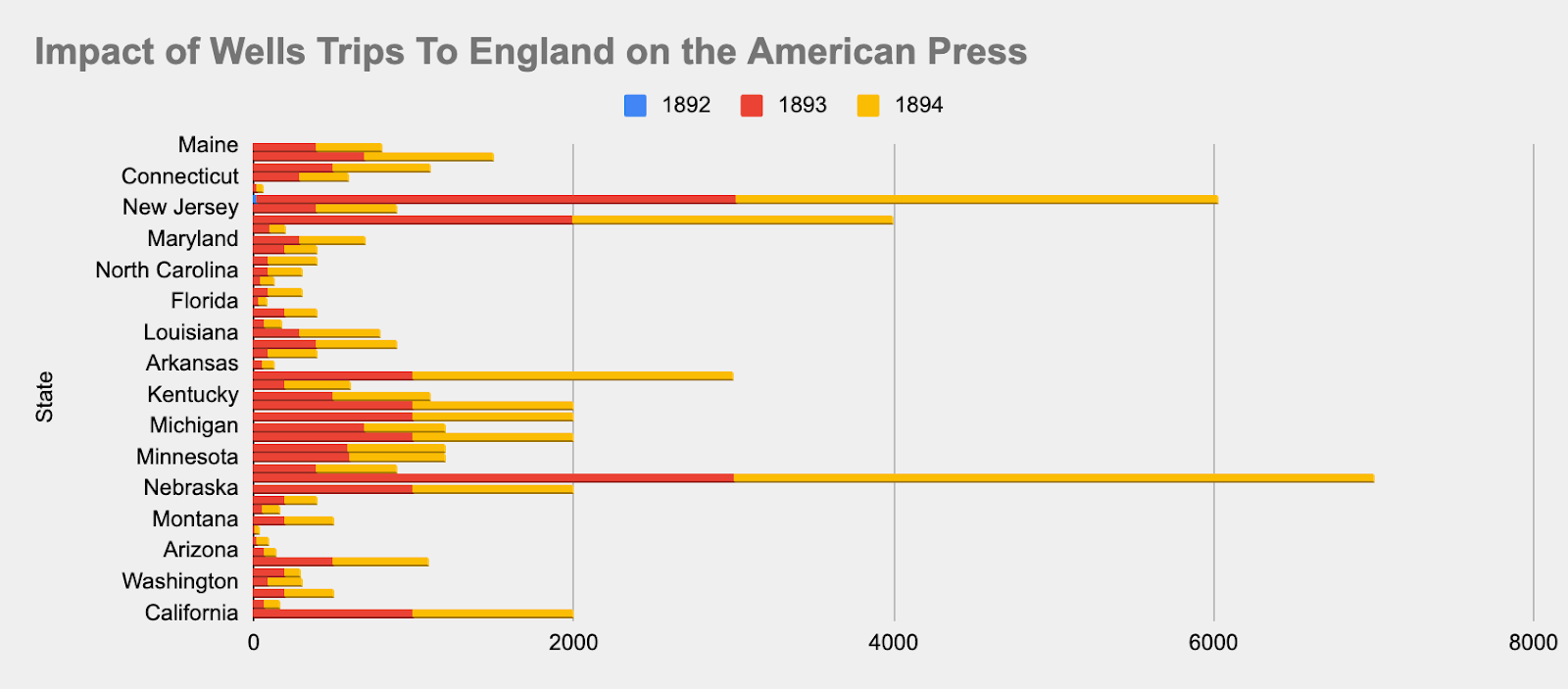

The Memphis papers did all they could to discredit Wells. Outside of their coverage, little was written in the South. In Virginia, the Richmond Dispatch ran a brief mocking report about Wells' overseas tour in June 1893.

“A certain 'Miss Ida B. Wells’” (colored) is in England lecturing about 'Lynch law in the south.” Owing to the lamentable fact that our English cousins do not study the geography of America as much as they ought, the result of those lectures is somewhat amusing. Many of her hearers think that she is talking about South America. Others consider her remarks about ‘mob law’ to apply to the whole of the United States….But really, if she wishes to stop lynching, she should appeal to the colored people; they can stop it by stopping the crime, which reduces it.” The story was reprinted in the Shenandoah Herald7

London Calling

Upon her return to the States, Wells worked with Douglass on a report about the exclusion of Black Americans at the World Expo. She decided to make Chicago her home and started writing for the well-established African American newspaper, The Chicago Conservator. While in the Windy City, she continued to be a part of the women’s efforts to organize clubs.

By the end of 1893, Wells was preparing to return to Great Britain for six months beginning in February. She was invited by Impey’s new organization, The Society for the Recognition of the Brotherhood of Man in England and Scotland.8

This time, she planned to do things differently. She needed an income while she was overseas, and she desperately wanted the white press to pay attention to this visit. Before she left, Wells met with William Penn Nixon, the editor of Inter-Ocean, a white newspaper, and the only US paper to denounce lynching. Nixon offered Wells a job as a correspondent, and the paper ran her articles while she was in England.

Once in Great Britain, Wells arranged meetings and interviews with newspaper editors, spoke with clergy, encouraged people to join Impey’s organization, and helped create a network to raise awareness.

While in Bristol, she spoke at a “drawing-room meeting” in someone’s home where 100 upper-class people gathered to hear her. During the meeting, Wells was asked what the civil authorities and the churches were doing to address her concerns. “I could only say that, despite the axiom that there is a remedy for every wrong, everybody in authority from the President of the United States down had declared their inability to do anything; and that the Christian bodies and moral associations do not touch the question,” she said, explaining,

“It is the easiest way to get along in the South - and those portions in the North where lynchings take place - to ignore the question altogether; our American Christians are too busy saving the souls of white Christians from burning in hell-fire to save the lives of Black ones from present burning in fires kindled by white Christians,” because, you see,

“The feelings of the people who commit these acts must not be hurt by protesting against this sort of thing, and so the bodies of the victims of mob hate must be sacrificed, and the country disgraced because of that fear to speak out.”

Wells spoke across Great Britain, sometimes twice a day -she spoke at churches, large public meetings, at YMCA Halls, and in private homes. During a six-week stay in London, she spoke at 35 gatherings and had more invitations than she could fill. She told the Inter-Ocean Chicago audience, she wished Americans would be willing to have such an “open discussion” about lynching.

This time, she won over the British people, and resolutions began to fill American Ambassador Thomas Baynard’s mailbox. The religious community led the way; their statements and letters of resolve were sent to the ambassador and were printed in the British press. The Baptist Union’s resolution appeared in every London Newspaper and the Christian World. 9

The people of the South noticed. “From one end of the United States to the other, press and pulpit were stung by the criticism of press and pulpit abroad, and began to turn the searchlight on lynching as never before,” according to Wells.

The Memphis Commercial tried to intervene but ended up making things worse for themselves. In a righteous tone that “shocked” the English, the paper denounced Ida B. Wells, impugned her character, and encouraged the British not to listen to her. The editors “flooded England with copies of that issue of their paper.”

Only two publications, the first being the Liverpool Daily Post, acknowledged the Commercial’s screed, saying if they reprinted it as requested, they would infringe on libel law. Besides, they wrote, there wasn’t much that could be said to justify “the existence of lynch law.”

The nearby Liverpool Weekly Review added to the criticism, telling the American South, lynchings “constitute a lamentable, sickening list, at once a disgrace and a degradation to 19th century sense and feeling. Whites of America may not think so; British Christianity does, and happily all the scurrility of the American press won’t alter the facts.”

Wells noted in Crusade for Justice how gratifying it felt to be defended in such a way - unsolicited - when at home she never had a chance to address her detractors and be heard.

The southern press attempts to discredit Wells, actually boosted her case. After the Memphis paper’s rebuke, she was invited to a Parliamentary Breakfast. At the meeting, held at the Westminster Palace Hotel, the London Antilynching Committee was formed to help agitate and assist in bringing down lynch law in the United States. It was headed up by the Duke of Argyle, and among the founding members were the Archbishop of Canterbury, members of Parliament, and editors of major daily newspapers.

The British committee gave long sought credibility to the cause, it pressured the American press in a way the African American newspapers could not, and it inspired an economic boycott of Southern cotton among British manufacturers.

Rebuttal

The strategy employed on the second tour worked. The Northern white press awoke to Ida B. Wells' message and the scourge of lynching. They became relentless in their coverage, and reporters were constantly asking southern congressional delegations to react and respond. While the Southern press, concerned about a British committee investigating mob law, orchestrated a chorus of denunciations of Wells in an attempt to drum up divisions. They quoted “prominent” men from Richmond to Charleston to Savannah.

“There is no doubt that the propaganda begun by Ida B. Wells in England and continued in this country with increasing vigor, boldness, and recklessness as to facts, is beginning to have an effect in the south, but not such an effect as the black crusader has no doubt hoped would result from her sensational efforts. The entire affair, with its latest developments, makes more distinct and clear the actual conditions that exist between the two races in the south,” declared Missouri’s St. Joseph Gazette.

When the Black Methodists endorsed Wells, the press in Mississippi said, “Sermons full of hatred and bitterness against the white people of the state are being nightly preached.”

The Baptist Preacher’s Association called on an English pastor working in Norfolk, Va., Rev. JJ Hall, to write home in an effort to convince the British not to trust Wells.

On July 14, 1894, Hall sent a lengthy report that defended lynching in the American South and attacked Wells’ credibility to The Christian World in London. He implored them to publish it, “Our English people have been misinformed and acted, we think, unwisely in listening too readily to those who slander a great and good people. We have a right to expect better things from those who are so closely allied to us in religion and race. Be patient and learn the whole truth, and when this is done, the vapor of our slanderers will pass away like a dream.”

The diatribe featured letters he solicited from Southern Governors. Among them, Virginia’s newly elected Gov. Charles Triplett O’Ferrall wrote on June 7, 1894, “Twice during my five months as Governor, I have called out white troops to protect negroes [sic], who were charged with the most horrible of all crimes, and on both occasions they were afforded the fullest protection of law. In each instance, at the cost of hundreds of dollars to the State, the prisoners were saved from all sorts of violence and allowed the fairest and most impartial of trials. This action in itself will, without further expressions, show my views on lynching.”

Neither the Christian World nor any of the other publications Hall appealed to would publish his report. Ultimately, Hall’s father was able to get the Commonwealth of London to print the piece, according to the Norfolk Weekly. The Norfolk newspaper chastised the Christian World, calling it a “pretend” publication, and printed Hall’s report and the Governors’ letters in full, taking up every column inch of page 2 of the broadsheet on September 19, 1894.

Wells later wrote, “My success in England alarmed the people of the South, and some courageous Southern editors attacked me personally in their papers, and then sent copies of the papers to England to be spread broadcast there.”

The Response From Great Britain Was Swift

A member of the Anti-Lynching Committee, Richard H. Edmonds, editor of the Manufacturer’s Record, wrote in the London Times, “Sneering at the Anti-Lynching Committee will do no good,” because the public opinion of Great Britain is behind them. “It may not be generally known in the United States, but while the Southern and some of the Northern newspapers are making a target of Miss Wells, the young colored woman who started this English movement…the strongest sort of sentiment” supports it from Unionists to Home Rulers, from Labor to Socialists - even the Conservatives are on board. It includes the leadership of the most powerful British Journals and a host of minor publications, and every religious press from the Kingdom.

Back In The USA

It was time. The British told Wells it was time to go home: “This is the time to strike the blow.” The network in Britain was ready, they told her, “People here only need their duty pointed out to them and they will do it. This latter-day slavery must be put down.”

Upon her return, Wells appeared at an AME Church in New York City. According to the New York Herald’s July 30 issue, Wells told the Black community gathered there, “For two years I have been trying to tell the truth about these matters, a truth, by the way, for hinting at which I was banished from my home. I went to England after making vain efforts to get a hearing in my own country …the English people were incredulous when I told them of the lynchings in the South. They thought I was crazy when I told them how men and half-grown boys lynched innocent colored men and then mutilated their bodies, even cutting off the fingers and toes at times and carrying them around in their pockets for days as souvenirs of the occasion.”

Back in the states, Wells said everyone kept asking her, “What can I do?” Her advice was simple: she told them to counter the lies by sharing the truth and the facts wherever possible. She said, share them at any gathering, at church - take every opportunity. She encouraged them to organize, to form associations and clubs, and keep the anti-lynching conversation alive.

This drew the ire of a Mississippi newspaper, “She advocates the formation of clubs and associations among the negroes [sic] for the peaceable and lawful discouragement of lynching… such organizations will scarcely be tolerated, for the reason that the negroes [sic] can only argue against lynching by extenuating rape, murder and lawlessness, and this the whites will not permit.”

Pressure Mounts

Much to the chagrin of the South’s standard bearers, the endorsements for Wells' anti-lynching campaign kept coming. The Black AME Potomac District Conference read out a report by Rev. D.P. Seaton entitled “Moral Effect of the Ida B. Wells Crusade Against Lynching.” They enthusiastically endorsed Wells and said the antilynching crusade was being felt around the world and waking up the country from “its long sleep.”10

William Lloyd Garrison said, “A year ago the South derided and resented Northern protests; today it listens, explains and apologizes for its uncovered cruelties. Surely a great triumph for a little woman to accomplish! It is the power of truth simply and unreservedly spoken, for her language was inadequate to describe the horrors exposed.”

A New York reporter contacted Virginia Gov. O’Ferrall for his reaction to the British Anti-Lynching group’s planned investigation. His dismissive reply ran in the Virginian Pilot on Sept. 11, 1894.

“What information do they seek? Do they want to know that the white people in the South have lynched negroes whose miserable lusts led them to the commission of a black crime upon white women? If so, they need not investigate, for such is the fact.”

“Do they desire to know that this has been done by injured communities for the protection of their white women and to save the victims of these fiends from the humiliation of testifying in courts? If so, this is the fact.

“Do they want to know whether there was any doubt as to the guilt of the men lynched? If so, for the satisfaction of their yearning souls, they could have ascertained without encountering the perils of a sea trip that their guilt was clear in every instance.

“…In Virginia, the authorities in every case have asserted all their power to suppress the lynching spirit, and within the last few months, I have protected from violence with military, at heavy expense to the State, three negroes who were charged with outraging white women. They had fair trials, were convicted, and executed. While lynch law is to be condemned and every effort has been and will be made to suppress it in the South, without the advice of those would-be philanthropists who have taken so much upon themselves, lynchings will surely cease when the crime of outrage ceases. These sympathetic Englishmen might find missionary work among the negroes of the South in warning them against the consequences of the forcible gratification of their devilish lusts.”

At almost the same time that this ran in the newspapers, the Afro-American Press Association meeting in Richmond for a convention endorsed Wells. John Mitchell, W. Calvin Chase, and John C. Daney had invited Gov. O’Ferrall to speak to their group. O’Ferrall sent a letter in his stead, explaining he refused to speak to a group that supported a woman who slandered the southern people. Yet, he also took the opportunity to condemn lynching and promised to uphold the law.

“As long as I am Governor of Virginia every man, whether white or colored, whatever the charge against him may be, shall have a trial by judge and jury, if I have to exert all the powers given me by the Constituiton and laws of Virginia, and should any case of lynching occur, I shall endeavor to enforce the law against the lynchers.”

O’Ferrall continued, “It looks very much to me as though the work of Ida Wells was a deep-laid scheme to check as far as may be the progress of the South, and every good citizen, white and colored, should feel an interest in refuting her vilifications rather than sanctioning them, as your convention did last evening. She and her supporters certainly stirred up a feeling against her own race, which did not exist prior to her crusade. The people of the South, who have labored so assiduously for nearly a generation now to recuperate and build up their waste places, will not take kindly to the efforts which this woman and her followers are making to bring reproach upon their section, and create the impression that it is a land of lawlessness and disorder.”

Wells’ Antilynching Crusade Catches Steam in the U.S.

Ida B. Wells returned late in the summer of 1894, and by the end of the year, anti-lynching groups were being organized in the United States. Just months later, in the Spring of 1895, she published the Red Record, Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, where she documented lynchings that happened from the time of the Emancipation Proclamation to 1895, using reports collected from “mainstream” white news outlets.

“It becomes a painful duty of the Negro [sic] to reproduce a record which shows that a large portion of the American people avow anarchy, condone murder, and defy the contempt of civilization. These pages are written in no spirit of vindictiveness,” she stated in the report.

The report’s findings include: of the 1,115 Black men, women, and children tortured and lynched from 1882-1894, only 348 were charged with rape. “Nearly 700 of these persons were lynched for any other reason which could be manufactured by a mob wishing to indulge in a lynching bee.”

At the end, Wells makes a simple plea for justice, writing, “Therefore, we demand a fair trial by law for those accused of crime, and punishment by law after honest conviction. No maudlin sympathy for criminals is solicited, but we do ask that the law shall punish all alike. We earnestly desire those that control the forces which make public sentiment to join with us in the demand. Surely the humanitarian spirit of this country, which reaches out to denounce the treatment of the Russian Jews, the Armenian Christians, the laboring poor of Europe, the Siberian exiles and the native women of India, will not longer refuse to lift its voice on this subject. If it were known that the cannibals or the savage Indians had burned three human beings alive in the past two years, the whole of Christendom would be roused to devise ways and means to put a stop to it. Can you remain silent and inactive when such things are done in our own community and country? Is your duty to humanity in the United States less binding?”

The Almost Lynching of Albert Hawkins in Alexandria

That same year, at the end of October, Albert Hawkins, a Black boy of 15, was accused of criminal assault against a 12-year-old white girl in Alexandria County. He was almost lynched by a mob that followed the Magistrate to Alexandria City, where Hawkins was jailed for safekeeping. A rushed trial the next morning ended in a death sentence for the boy.11

The following day, Gov. O’Ferrall summoned Alexandria Commonwealth’s Attorney Leonard Marbury (who would also be the Commonwealth Attorney when Joseph McCoy would be lynched in 1897) and the Judge in the case, D.M. Chichester, to Richmond. State Attorney General Scott and the Governor wanted to better understand “the lawlessness in Alexandria,” according to the Alexandria Gazette. He told them their input would be included in his address at the opening of the General Assembly.

Virginia’s Governor Proposes Antilynching Legislation

On December 4, when Gov. O’Ferrall addressed the General Assembly at the opening of the session, the ex-confederate soldier proposed legislation to address mob law. While it does not prioritize Black Virginians’ constitutional rights, it does try to reimpose due process for them, even if in a performative manner. Evidence that Wells' campaign had an impact on Virginia.

“With pain and mortification, I bring to your attention the frequent taking of human life without due process of law within the borders of our State,” O’Ferrall stated. “ I know there is a crime too horrible to mention, so black as to cry for vengeance, but even the commission of that crime cannot warrant a resort to violence.”

The Governor then proposed legislation that would require counties where lynchings took place to pay $200 for every 1,000 people, not to exceed $10,000, to the state for the public schools. When the Mayor or Sheriff called on the military to protect a threatened prisoner, an additional fee to cover those costs would be charged to the citizens of the county.

He also proposed that any officers who allow a mob to take a prisoner should be suspended until a jury can decide if he should be removed. And any prisoner taken by a mob, or if he is killed, his family, could be paid damages by the officer who failed to protect him. The burden would be on that officer to “prove” he “exhausted all means in his power to prevent the taking of the prisoner from his custody.”

Finally, O’Ferrall said rape and attempted rape should carry a penalty of death. And, he said, rape cases should take precedence in court over all other pending cases. Such a law, he believed, “would put an end to lynchings in Virginia.”

In Her Words

Wells believed the second trip overseas was responsible for helping the Black voice break through in America, inhibiting the false and reckless rhetoric espoused by prominent people that condoned lynching, and most of all, seemed to account for a steady decline in lynchings.

“The universally accepted statement that lynching was necessary because of criminal assaults of Black men on white women has almost entirely ceased to be believed. This was because of the power of truth, which the British people afforded me the opportunity to present. They gave a press and a platform from which to tell the Negroe’s side of the gruesome story of lynching, and to appeal to Christian and moral force for help in the demand that every accused person be given a fair trial by law and not by the mob,” Wells wrote in Crusade for Justice.

Epilogue

“Crime has the power to reproduce itself and create conditions favorable to its own existence. It sometimes seems we are deserted by earth and Heaven, yet we must still think, speak, and work, and trust in the power of a merciful God for final deliverance.” – Frederick Douglass

Further reading:

A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States 1892, 1893, 1894, Ida B. Wells, 1895.

Why Is The Negro Lynched? By the late Frederick Douglass, 1895, Printed by John Whitby and Sons, Ltd. Reprinted by permission from “The A.M.E. Church Review” for Memorial Distribution, by a few of his English friends.

Crusade for Justice, The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, Edited by Alfreda M. Duster, Negro American Biographies and Autobiographies Series Editor John Hope Franklin, University of Chicago Press, 1870.

Endnotes:

1. Wells was a school teacher at an African American school in Memphis, and in 1887, she wrote for some church newspapers and Black weeklies. In 1889, she was hired to also work at the African American newspaper, Free Speech and Headlight. Wells used her savings to buy a ⅓ share of the newspaper, sharing ownership with Rev. Taylor Nightingale and J.L. Flemming. In 1891, although a recognized teacher, she was fired after writing a series of editorials criticizing the Memphis Board of Education for conditions in African American schools. That same year, Nightingale was run out of town, and Wells shared the paper with Flemming, who was the business manager; she shortened the name to Free Speech.

Ida B. Wells was barely 5 feet tall.

“The most remarkable thing about Ida B. Wells-Barnett is not that she fought lynching and other forms of barbarism. It is rather that she fought a lonely and almost single-handed fight, with the single-mindedness of a crusader, long before men or women of any race entered the arena; and the measure of success she achieved goes far beyond the credit she had been given in the history of the country,” p. xxxii, Introduction, Crusade for Justice.

“Ida Wells was not only opposed by whites, but some of her own people were often hostile, impugning her motives. Fearful that her tactics and strategy might bring retribution upon them, some actually repudiated her.” p. xxxi, Introduction, Crusade for Justice.

2. In 1872, two days after whites attacked the Black Odd Fellows from Washington and Alexandria during a funeral march, and the Alexandria Light Infantry responded without being called out by the Mayor, a civil rights meeting to show support for Sen. Charles Sumner’s Civil Rights Act was held at the Black Methodist Church on Washington Street. The resolution makes clear they were not being treated equally and the law was being violated, “Whereas we, a large portion of the colored voters of Virginia, feel that we are still deprived of the equal enjoyment of rights pertaining to citizenship in that we are discriminated against on railroads and steamboats; the hotel proprietors; are excluded from the equal enjoyment of advantages furnished by places of amusement and instruction. In our own State, by an artful evasion of the law, we are excluded from sitting juries, notwithstanding this right is guaranteed to us by the constitution of our State: Therefore,

Resolved. That we heartily endorse the bill introduced into the United States Senate by Hon. Charles Sumner, and known as the supplementary civil rights bill, and believe that its passage and proper enforcement will correct the injustices under which we suffer.

Resolved, that we contemptuously reject the assertion that we are attempting to force ourselves into any one’s society. We are well aware that social relations can not be regulated by law. We only ask that we be accorded full civil rights in common with other citizens. Resolved, that we earnestly and respectfully petition the Congress of the United States to pass said bill.” Sat. May 11, 1872, Washington Chronicle p. 1.

3. The US Supreme Court in 1883 ruled that the 14th Amendment didn't prohibit discrimination by private companies and citizens. This wiped out the Civil Rights Act of 1875 enacted to enforce the 14th and 15th Amendments. The ruling meant that the Federal Government could not intervene when African Americans were discriminated against.

4. In Southern Horrors, Wells wrote: “The mob took possession of the People’s Grocery Company, helping themselves to food and drink, and destroyed what they could not eat or steal. The creditors had the place closed, and a few days later, what remained of the stock was sold at an auction. Thus, with the aid of the city and county authorities and the daily papers, that white grocer had indeed put an end to this rival Negro grocer as well as to his business.” And a little later, she said something similar about the Free Speech:

“Mr. Fleming, the business manager and owning a half interest in the Free Speech, had to leave town to escape the mob, and was afterwards ordered not to return; letters and telegrams sent to me in New York, where I was spending my vacation, advised me that bodily harm awaited my return. Creditors took possession of the office and sold the outfit, and the Free Speech was as if it had never been.”

5. Frederick Douglass told Wells he, too, had been “troubled by the increasing number of lynchings, and had begun to believe it true that there was increasing lasciviousness on the part of Negroes.” Crusade for Justice.

6. Wells, who wanted to investigate every lynching, used $150 given to her by women in D.C. to pay a white firm to send a private investigator to Texas. Unfortunately, the firm sent a southerner who gave Wells worthless information. Later, she would implore her community to cultivate detectives to investigate each lynching and then publish the facts in Black newspapers beside the versions printed in white southern newspapers.

7. Shenandoah Herald reran the Richmond Dispatch brief about Wells on June 23, 1893, p. 2. This was the only story in Virginia that acknowledged Wells's trip. The Roanoke Press in July 1893 claimed the co-publisher of the Free Press, J.L. Flemming, was run out of Marion, Ark., and his ear cut off. This story was not verified in Wells' autobiography; she did write about what happened to Flemming after Memphis, but she never mentioned his returning to Marion and being run out of town without his ear.

8. The interest in Wells’ 1883 tour enabled Impey to turn her Anti-Caste’s readership into a movement. The collective decided to call themselves the Society for the Recognition of the Brotherhood of Man (SRBM).

9. Resolutions were passed against lynching by the Baptist Union, the National Baptist, Congregational, Unitarian, and temperance unions at their annual meetings in May in London. The Aborigines Protection Society, led by Lord Northbourne, passed a similar resolution as did the Protestant Alliance, the Women’s Protestant Union, congregations at Bloomsbury Chapel, Belgravia Congregational Church, and others. Each time a letter with the resolution was sent to the American Ambassador Thomas Baynard. Crusade, p. 176

10. Baltimore Sun, September 14, 1894, p. 10

*In the Red Record, published in 1895, Wells explained why it was still necessary,“If the Southern people, in defense of their lawlessness, would tell the truth and admit that colored men and women are lynched for almost any offense, from murder to a misdemeanor, there would not now be the necessity for this defense. But when they intentionally, maliciously, and constantly belie the record and bolster up these falsehoods by the words of legislators, preachers, governors, and bishops, then the Negro must give to the world his side of the awful story.”

11. Albert Hawkins, 15, received a second trial after the Black communities of Washington and Alexandria raised money and hired a lawyer for him. It was found that in the rush to judgment at the first trial, the indictment was not written into the minute book or properly registered. A second trial was held in November 1895, and the jury found Hawkins guilty but sentenced him to the maximum of 18 years in prison.

Research and writing by Tiffany D. Pache