African American Heritage Trail - North Waterfront Route

North Waterfront Route

African American Heritage Trail

North Waterfront Route

from the Foot of King Street

The South Waterfront Route and future segments can be viewed by clicking the button below.

African American Heritage Trails (Main Page)

Even before the founding of the City of Alexandria in 1749, Africans and their descendants, enslaved and free, have lived and worked along the waterfront, making significant contributions to the local economy and culture. In the 1820s and 1830s, Alexandria became home to the largest domestic slave trading firm, which profited from the sale and trafficking of enslaved African Americans from the Chesapeake to the Deep South. The Civil War revolutionized social and economic relations, and newly freed African Americans found new job opportunities as a result of the waterfront’s industrialization. The Potomac River played an important role in leisure activities too, including picnicking, boating, and fishing, much as it does for Alexandrians and visitors today.

We envision the African American Heritage Trail as comprising several interconnecting routes in the City of Alexandria. Together, these trails illuminate the history of the African American community over a span of several centuries. The North Trail Route is the first in a series of trails covering the waterfront. The African American Heritage Trail Committee created this walking tour through history, with the support of the Office of Historic Alexandria.

The South Trail was added in 2023. This and future segments can be viewed by clicking the button below.

African American Heritage Trails

Thank you to members of the African American Heritage Trail Committee: Councilman John Chapman, Susan Cohen, Gwen Day-Fuller, Maddy McCoy, Krystyn Moon (Chair), McArthur Myers, and Ted Pulliam. Special thanks to Indy McCall for her contributions. Office of Historic Alexandria support provided by staff of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum an the Alexandria Black History Museum.

Watch the Celebrate Juneteenth Along the Waterfront webinar featuring members of the African American Heritage Trail Committee as they share a behind-the-scenes look at this community history project.

The StoryMap

Alexandria’s African American history is told through an online StoryMap and can be experienced in-home on your computer or on your smartphone as you walk the trail along the Potomac River. The relatively flat walk takes you along the waterfront from the foot of King Street and Waterfront Park to the corner of North Fairfax and Montgomery streets, about a mile in distance. The walking trail lasts about 45 minutes at a leisurely pace.

This webpage presents more in-depth information about the stops highlighted in the StoryMap.

Stop 1: Land-making Efforts

Trail Sign: Foot of King Street

18th Century

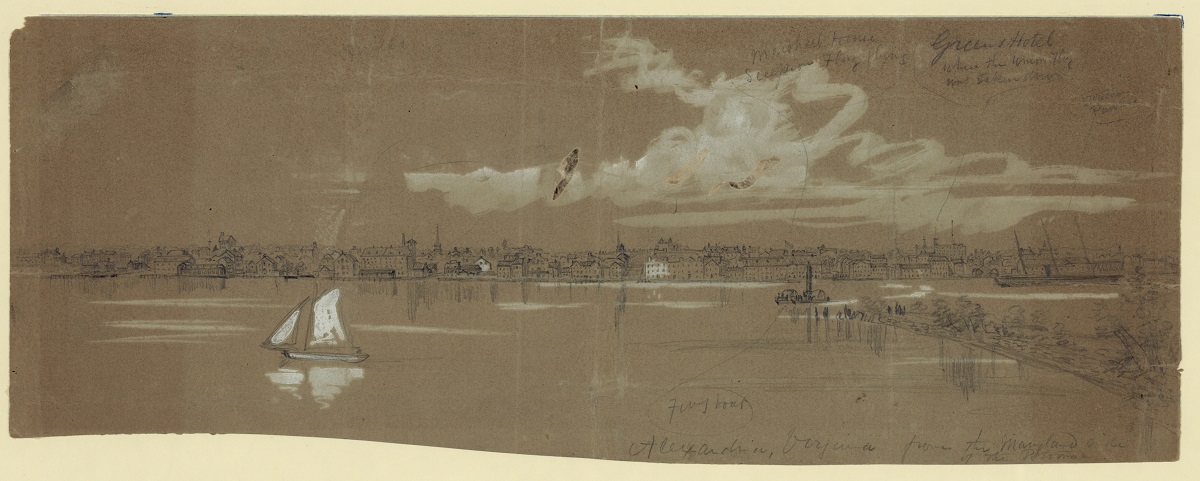

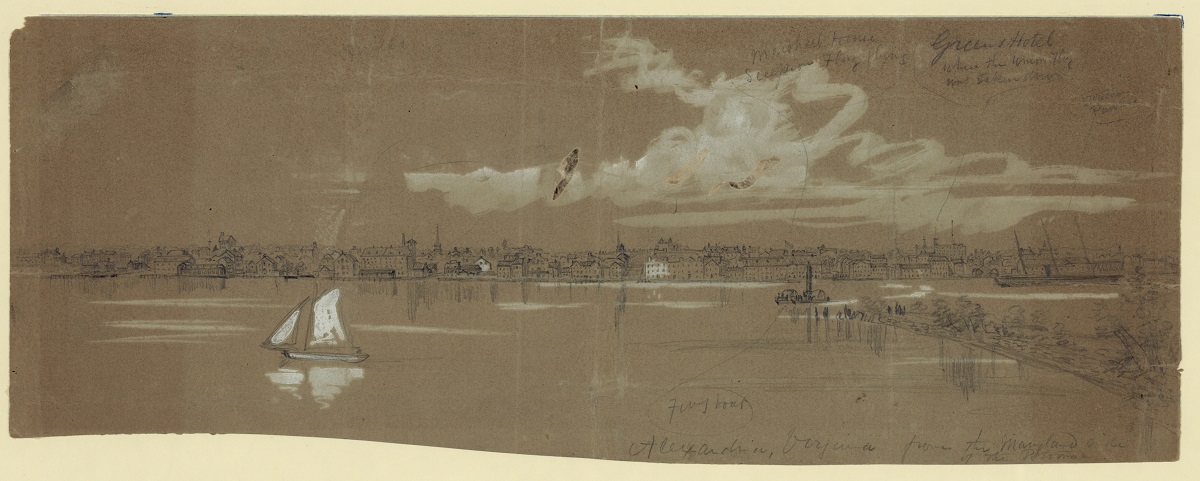

Alexandria was founded in 1749 as a tobacco port town. The growth of mercantile activities in the late 18th century led to the filling in of the original crescent-shaped bay, physically changing the landscape of the waterfront. This land making project enabled the wharves to better reach the shipping channels farther out in the Potomac River.

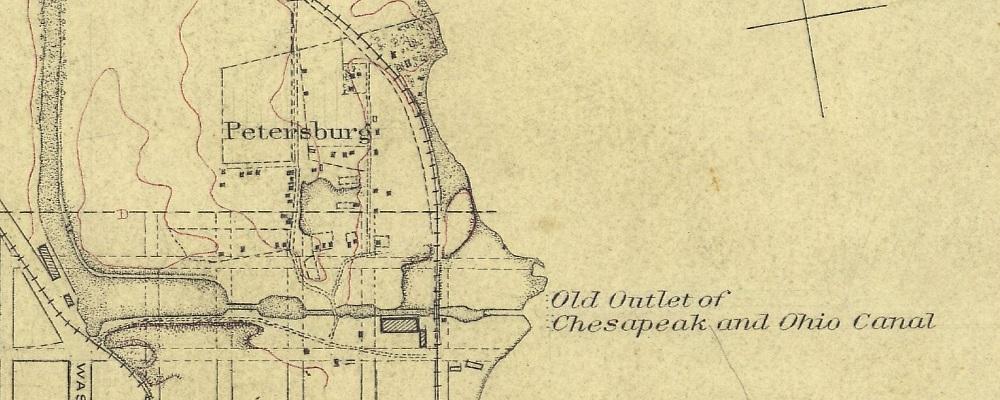

George Washington, a surveyor in his early years, drew this map of Alexandria at the time of the town’s founding in 1749. The “x” marked on the map shows the place where you are standing at the foot of King Street in what was once the tidal mudflats of the Potomac River. Turning west and looking up King Street, you can see a slight rise where the steep banks of the original shoreline stood before the filling of the bay. The entire area around lower King Street east of Lee Street (formerly called Water Street) sits on the new land made by early Alexandrians.

We know very little about the individuals engaged in or assigned to the task of making land in late 18th and early 19th century Alexandria, but the labor force likely included African Americans, free and enslaved, and white workers, possibly indentured. The first U.S. Census in 1790 identified 2,748 individuals in Alexandria, including 595 African Americans representing nearly 22% of the population. The African American population included 543 enslaved people and 52 African Americans listed as free (about 11% of the total African American population). A decade later, Alexandria’s African American population had reached 1,244, with an increase in the free portion of the entire African American population to 29%. [1]

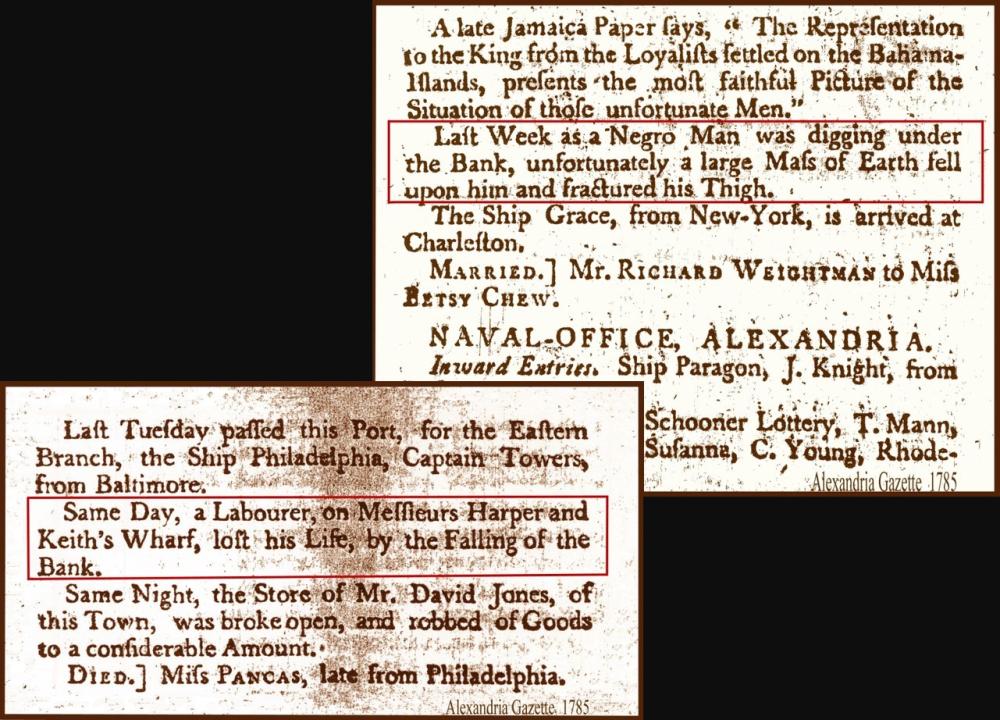

On April 14, 1785, the Alexandria Gazette reported that “Last week as a Negro Man was digging under the Bank, unfortunately a large Mass of Earth fell upon him and fractured his Thigh.” Another notice, on September 7th of the same year, stated that “...a Labourer, on Messieurs Harper and Keith’s Wharf, lost his Life, by the falling of the Bank.” These brief accounts shed light on a largely undocumented, yet massive and costly, effort to fill in Alexandria’s mudflats with earth. Much of the earthen fill came from high banks at the edge of the bay. Residents used the earth, held in place by wharves, piers, and derelict ship hulls to create useable land and reach the deeper channel of the river.

Stop 2: Torpedo Factory

105 N. Union Street

Trail Sign: Torpedo Factory

20th Century

The U.S. Naval Torpedo Factory Station was planned during World War I, but construction did not begin until November 18, 1918, the day after the war ended. The factory manufactured Mark III torpedoes for the next five years, and in 1937 began production of Mark XIV torpedoes, an example of which is displayed in the main hall today. After World War II, the Torpedo Factory buildings were converted into the Federal Records Center. The City of Alexandria purchased the buildings from the federal government in 1969, and the Art Center was established in 1974. Today, the Torpedo Factory Art Center is a major cultural center in Alexandria. It is the home of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum, The Art League and studios and galleries of 165 working artists, all of which are open to the public.

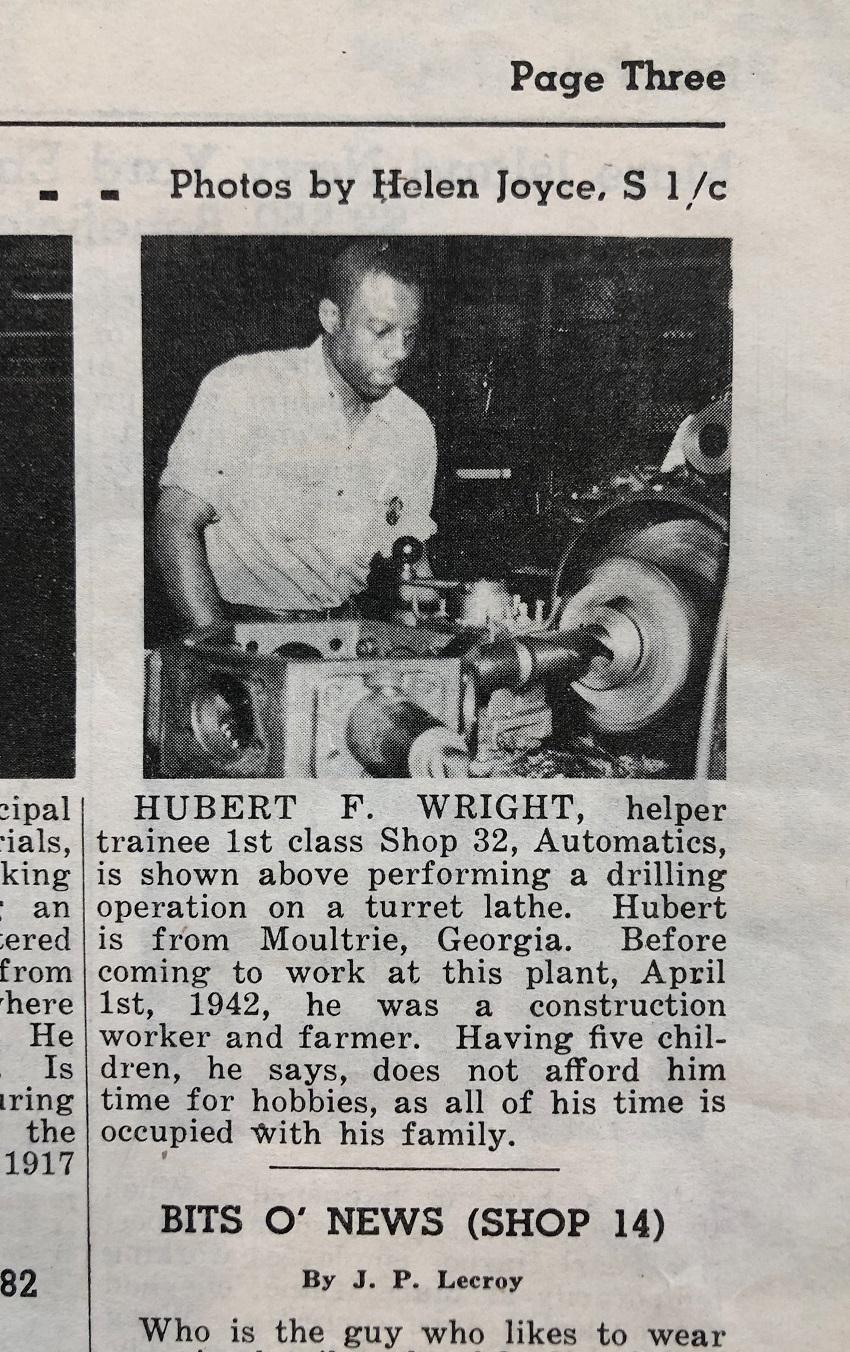

Alexandria’s Torpedo Station, begun in 1918, has served numerous purposes for the American military until the City of Alexandria bought the complex in 1969. The station failed to open before the end of World War I, but the federal government maintained the building through the interwar period. At the time, African American men and women had limited job opportunities in the federal government, but the desegregation of the defense industries through Executive Order 8802 in 1941 began the slow and uneven process of integrating the station’s workforce. [2] Within months, African American men were working as machinists on the torpedo factory floor. The U.S. Navy transferred Aaron P. Hatcher, previously stationed at the Washington Navy Yard, to work as a machinist at the station in June 1941. He worked for three years in Alexandria, before moving to Nashville, Tennessee where he graduated from the Aviation Machinist School in 1945. [3] Wicklef Jackson, another former Washington Navy Yard employee, served lunches from a pushcart starting in 1929 before the military transferred him to the Production Department where he was a laborer. After a brief stint in the military, Jackson returned to the Alexandria Torpedo Station and continued to be employed there after the war. [4]

One of the Alexandria Torpedo Station’s other most important (and least recognized) moments was its use for the storage, processing, and return of records captured during World War II, the largest archival project ever undertaken by the U.S. government. Allied Forces acknowledged that the war threatened priceless works of art, monuments, and archival collections, and sought to remove materials from war zones. At first, the British and American military used these papers for intelligence information and later to prosecute war crimes, including as evidence in the Nuremberg trials. However, the Adjutant General’s office followed by the National Archives recognized the collection’s broader historical significance and requested the assistance of the American Historical Association (AHA) in processing the papers, which were housed at the Torpedo Station from 1947 through 1968. [5]

The names of the scholars who oversaw the collection are well known; however, unnamed government employees, contractors, and military personnel, whom we find in photographs, completed much of the day-to-day work. Many of these workers were also African Americans and the photos highlight the federal government’s increasingly desegregated workforce.

Stop 3: Carlyle's Wharf

Foot of Cameron

18th Century

At the foot of Cameron Street stood what was once John Carlyle and John Dalton’s wharf extending from the shore into the Potomac River. In 1759, just 10 years after the town was established, the Alexandria Trustees granted Carlyle and Dalton the right to construct a “good and convenient landing at Cameron Street.” [6] Ships of all kinds, both transatlantic and intercoastal, arrived in Alexandria in the late colonial period at places such as Carlyle’s Wharf. Archaeology revealed that the wharf was built of yellow pine logs, some with the bark still attached, and notched together at the corners. The high-water table along the river contributed to the preservation of this wood structure.

Alexandria’s founding in 1749 coincided with the peak of British North America’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade. Between 1751 and 1775, British ships dominated the intercolonial and the transatlantic slave trade, bringing upwards of 900,000 African men, women, and children to the colonies. [7] Slave trading in the Chesapeake region, however, had its peak earlier in the century, and by the 1750s, most ships traveled to the Carolinas, Georgia, or New England.

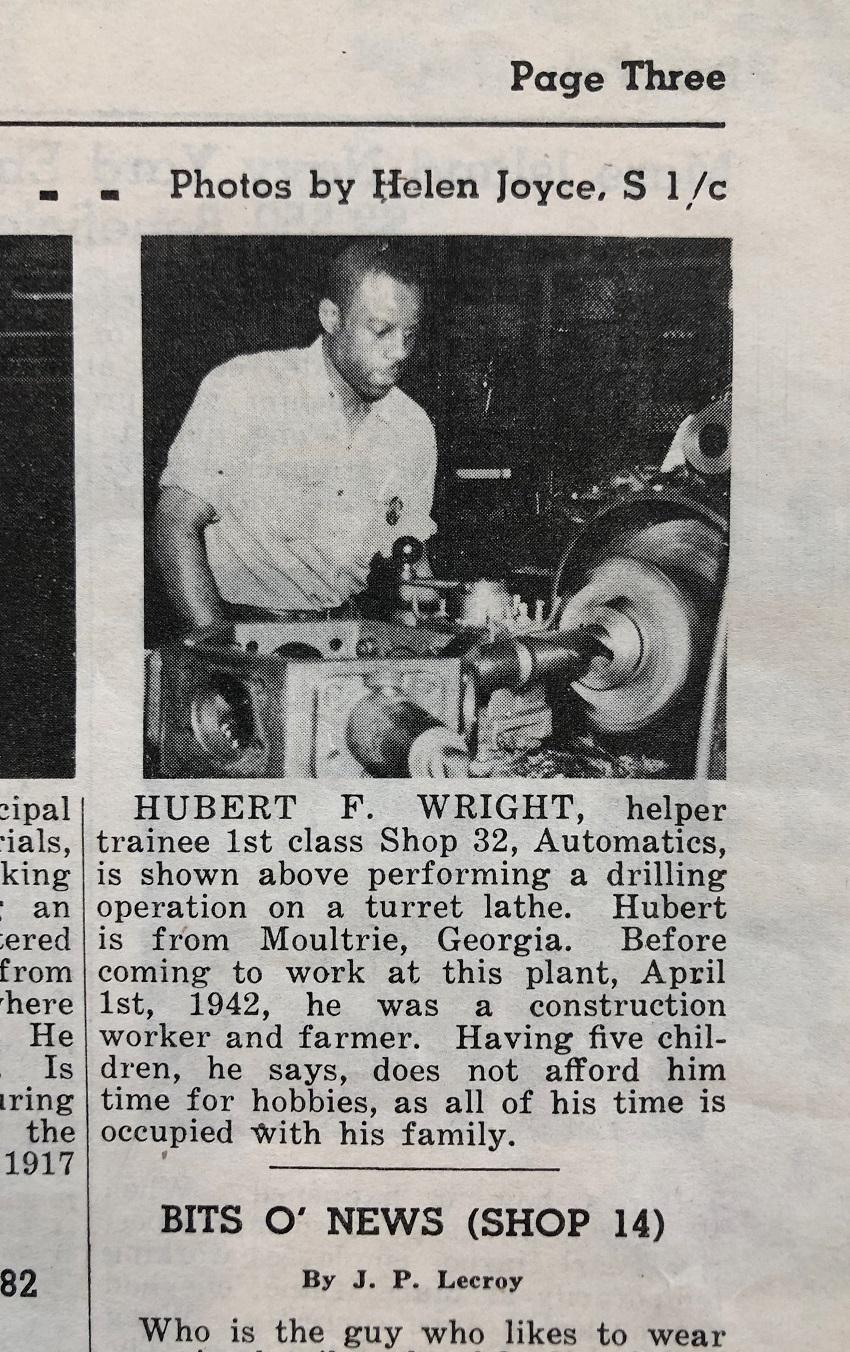

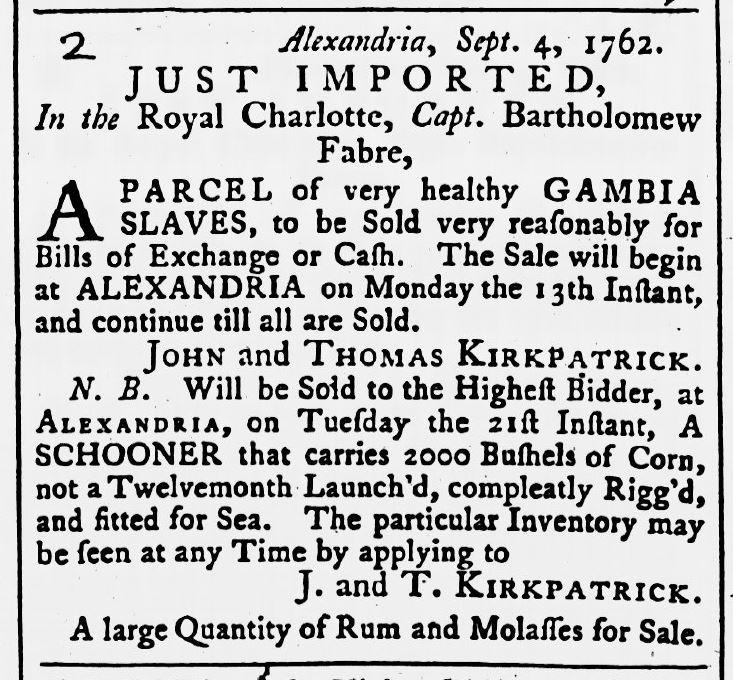

Although transatlantic slave trading had shifted away from the Chesapeake, ships from West Africa and the Caribbean arrived in the region through the late colonial period. Taxes imposed by Virginia’s colonial government impacted the international slave trade, and local slave owners, including George Washington, purchased enslaved people in Maryland. [8] When Virginia finally repealed a portion of its duties in 1761, ships returned to the Virginia side of the Chesapeake, including Alexandria. Colonial newspapers provide several examples. In September 1762, John and Thomas Kirkpatrick advertised in the Maryland Gazette the arrival of ship Royal Charlotte from Gambia, with a possible stop in the Caribbean. A year later, a Lucas Gawey brought enslaved people from St. Kitts on the schooner Industry and sold them at Kirkpatrick’s store. The ship Alice brought a “cargo of choice healthy SLAVES” from Senegal and Gambia in 1765 to Alexandria, with a stop at Hooe’s Ferry on the Occoquan River. [9]

By the 1770s, a burgeoning anti-slavery movement condemned the transatlantic slave trade. As a result, the colonial Maryland assembly banned transatlantic slave trade in 1774, and Virginia followed suit four years later. Additionally, planters in the Chesapeake no longer needed large influxes of laborers as they had in the 17th and early 18th centuries. The enslaved population was growing through natural reproduction, and the economy’s shift from tobacco to wheat required fewer laborers. Wars, embargoes, and new international boundaries in the latter part of the century also led to shifts in trading partners, with the newly established United States initially forced to end trade relations with British colonies in the Caribbean. Nevertheless, the federal government’s ban on participation in the transatlantic slave trade did little to discourage American merchants. Passed in 1807, the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves made it illegal for Americans to participate in the international slave trade starting January 1, 1808, the earliest date allowed by the United States Constitution. American slave traders, however, turned to markets in Cuba and Brazil where international slave trading remained legal. Once it became illegal to transport enslaved people from outside the United States, Alexandria soon became central to the still-legal domestic slave trade beginning in the 1820s, sending enslaved men and women through cities such as Charleston and New Orleans to other parts of the Deep South. [10]

Stop 4: Retrocession

City Marina

Trail Sign: Retrocession

19th Century

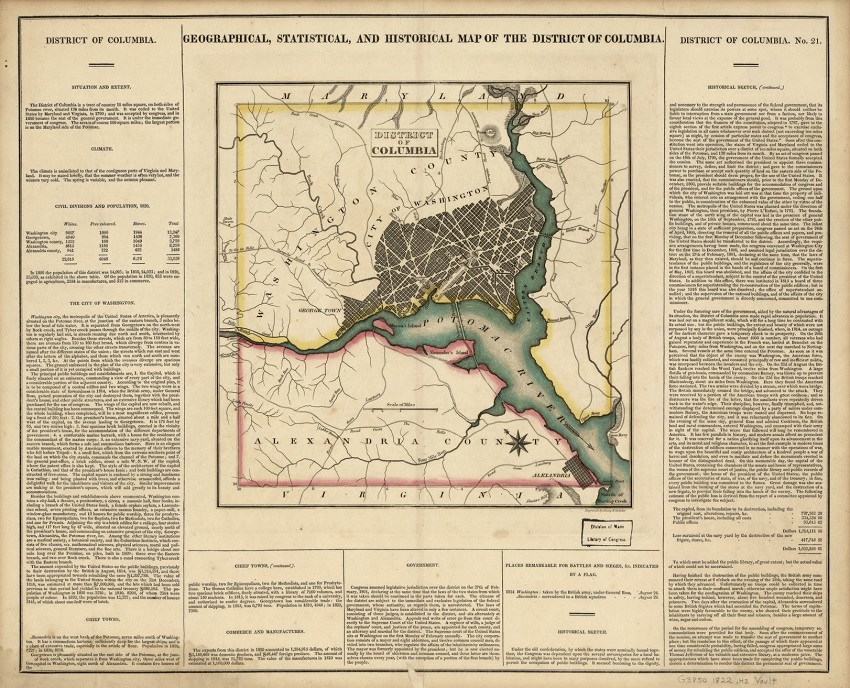

The boundaries of Washington, D.C. were originally a square, extending ten miles on each side. The first cornerstone marking the southernmost point of this new federal district was laid at Jones Point, about a mile to the south. In addition to its present boundaries containing land which used to belong to Maryland, the District of Columbia originally included approximately 30 square miles of land on the Virginia side of the Potomac River, including most of Old Town Alexandria and all of present-day Arlington County.

In 1846, Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia. Virginia had ceded Alexandria to the new seat of the national government 55 years earlier, and it became known as “Alexandria, D.C.” Now, however, the town’s white leaders wanted Alexandria to return to Virginia—to retrocede. [11]

Alexandria became part of the District on March 3, 1791 when, at President George Washington’s urging, Congress amended the law establishing the District to add Alexandria. [12] White Alexandrians eagerly sought their inclusion. They believed that because of Alexandria’s central location within the new country and its site on the Potomac, it could link the eastern and western regions to the advantage not only of Alexandrians but also the nation as a whole. [13]

This positive sentiment toward the District persisted as long as Alexandria’s economy thrived. After the War of 1812’s devastation and the expansion of Baltimore and New York’s trade relations in the west, Alexandrians began to notice problems with being part of the District. [14]

In October 1840, a referendum of white Alexandrians on retrocession resulted in a vote of 601 for and 158 against. Major concerns were Congress’ failure to support the town economically, the inability of District citizens to vote in national elections or for representation in Congress, and the power of Congress to pass legislation concerning “the property of the people of the District.” [15]

White Alexandrians were concerned particularly about Congress’s power to legislate over one type of “property,” enslaved people. Not only did Alexandrians own enslaved people, but also Alexandria was home to several substantial slave traders. Both groups were aware of abolitionists’ vigorous lobbying to end slavery in the District. William Jay’s Miscellaneous Writings on Slavery (1853) profiled the horrors that enslaved men and women faced in the District of Columbia, including Alexandria, and abolitionists’ attempts to end it. He argues: “In this District of ten miles square, there are six thousand slaves; and the laws under which they are held in bondage, are among the most cruel and wicked of all the slave laws in the United States. This District, moreover, place as it is under the immediate and absolute control of the national government, is the great slave mart of the North American continent.” [16] Jay and other abolitionists’ criticisms had become increasingly effective with northern politicians and readers, who also supported changing the laws in D.C. In Alexandria, both slave owners and traders wanted to retrocede in case abolitionists were successful. [17]

As a result of the efforts of white residents, Congress finally passed a bill providing for retrocession, which President James K. Polk signed on July 9, 1846. During the debate on the bill, its supporters did not mention slavery; the issue had become so controversial that it seemed wise not to raise the subject. [18] The act required another referendum on retrocession in Alexandria and the surrounding county. Only white men could vote, and the referendum passed 763 to 222. [19] On March 13, 1847, the Virginia General Assembly also approved a bill, accepting Alexandria back under its jurisdiction and completing the transfer. [20]

Prominent free African American leader Moses Hepburn wrote abolitionist Gerritt Smith that black Alexandrians greeted the news of the vote with prayers for “help and succor in this the hour of their need.” He also wrote of fear of what would happen once Virginia laws again applied to them: “our privileges which we have enjoyed for so many years will all be taken away.” [21] Moses Hepburn was correct to be afraid. Virginia laws stripped free African Americans of many of the rights that they had previously held in the District of Columbia, such as access to education and freedom of assembly. As a result, “between 1850 and 1860 the free black population of Alexandria fell from 15 to 11% of the total population.” [22]

Alexandria’s slave traders also were correct to worry. In 1850, Congress abolished the slave trade in the District, and many District slave traders soon moved across the river to Alexandria. [23]

Stop 5: Fishtown

Founder’s Park

Trail Sign: Fishtown

19th Century

In the 19th century, Fishtown existed at a time when the Potomac River was “full of business and fish.” The laborers were both free and enslaved people, many living seasonally on the wharves, cleaning and preparing the fish in Alexandria. One period description recounts:

“The change which early March comes over the waterside of this city, ranging between Princess and Oronoco streets… From a quiet, almost deserted suburb, Fishtown springs, in a few days, to be a mart, full of business and fish.” [24]

Every spring immense shoals of shad and herring came into the Potomac River. The earliest white settlers recognized this bounty, as had indigenous people before them, and fishing became an important and lucrative branch of colonial business. As people migrated up the Potomac River, so too did the fishing industry.

In the colonial period, salted fish, primarily shad and herring, was used as a main source of sustenance for Virginia’s enslaved population. As Virginia’s population grew, so did the demand for fish. In the earliest days of the town of Alexandria, the yearly fish harvest was delivered along various wharves and could be purchased with tobacco.

It took time for city government to finally decide a location for the unloading of fish along Alexandria’s waterfront in the early 19th century. At first, the city’s fish wharf, or fish market moved to the foot of Franklin Street and then to Jones Point. [25] By 1813, City authorities passed a law fixing the county wharf, as it was then called, as the official place for landing fish. The county wharf at West’s Point had been laid off as public property by the original town trustees in 1748. [26] Soon after, a collection of small wooden shacks and stalls sprang up in this area and became known as ‘Fishtown’ and is depicted on the Ewing map of 1845 as the “Fish Whf” at the foot of Oronoco Street. As the fish trade grew, so did the boundaries of Fishtown. By the 1850s, Fishtown incorporated all of the land from Princess to Oronoco Streets and from Union Street to the river. [27]

In compliance with local law, all fresh fish brought to Alexandria had to be landed at Fishtown. [28] Every spring Alexandria’s Committee on Public Property of the City Council offered Fishtown property for rent by public auction. [29] The white population viewed annual operations at Fishtown, which lasted from March to May, as a smelly spectacle and a source of gritty entertainment. However, for the local free African American and enslaved community, the yearly fishing season at Fishtown was a time of hard work and financial reward.

While white residents owned the businesses that processed fish, the majority of the laborers were free people of color. A smaller percentage of the workers were enslaved, hired out to work on the wharves by their slaveholders.

The fishing season brought up to 300 schooners and sloops and around 5,000 seine haulers, who used large nets. At Fishtown, up to 600 enslaved and free black laborers worked counting, beheading and gutting, cleaning and salting hundreds of thousands of fish. [30]

On the arrival of a vessel at the wharf, the agent of landing, after the inspection by the interested purchasers, proceeded to sell the cargo to the highest bidder. The purchaser then employed “off-bearers” to haul baskets of fish from the vessel onto the wharf. The “cleaners,” usually a small team of African American women, cut and washed the shad and herring. During the 1861 season, a fish cleaner was paid at the rate of 50 cents per hour for shad and 37 1/2 cents per thousand for herring. [31] A “good day’s haul” at Fishtown meant upwards of 700,000 shad and herring arriving daily at the wharf. The fish were then ready to be salted and packed into barrels. The offal of the fish was saved and sold as manure. [32]

Because of the sheer volume of people entering Alexandria during the fishing season, a seasonal hospitality industry, also run predominately by free men and women of color, emerged alongside it. Some of these dwellings were used as salting houses or for the sale and packing of fish spawn. The majority, however, were boarding houses and eating houses. These structures showed great ingenuity and resourcefulness. Individual lots were rented out for the construction of temporary wooden structures that were then dismantled at the end of the season. Business owners also rented wood for these buildings by the season. [33]

When Union military forces arrived in Alexandria on May 24, 1861, the fishing season was winding down. Upon arrival, the Union troops commandeered all the buildings at the fish wharf and used them for storage. Robert Henry Dogan, a free African American businessman in Fishtown, recalled that his eating-house was torn down, and the materials used for flooring and fuel. By the end of that summer, Union forces dismantled Fishtown, shutting down operations for the duration of the war. [34]

In the decades after the Civil War, the annual fish harvest went into a slow decline. The fishing industry had undergone some changes but most significantly, the Potomac River had simply been overfished. Other jurisdictions had experienced this problem and enacted regulations to protect migratory fish. The Virginia Commissioner of Fisheries pressed for similar laws to be passed, but politicians in Richmond refused. By 1920, Alexandria’s once vibrant fishing industry and, by extension, Fishtown was gone. [35]

Stop 6: Industry

Foot of Oronoco Street

20th Century

Alexandria’s waterfront experienced a period of rapid industrialization after the Civil War, and many of these factories, plants, and yards provided jobs for African American men. In the late 19th century, large numbers of African Americans migrated to the Washington metropolitan area from rural regions in the South, looking not only for employment, but also educational opportunities for their children and protection from white-on-black violence. Alexandria, although it offered different opportunities in comparison to rural areas, was still a segregated city, which impacted every aspect of people’s lives.

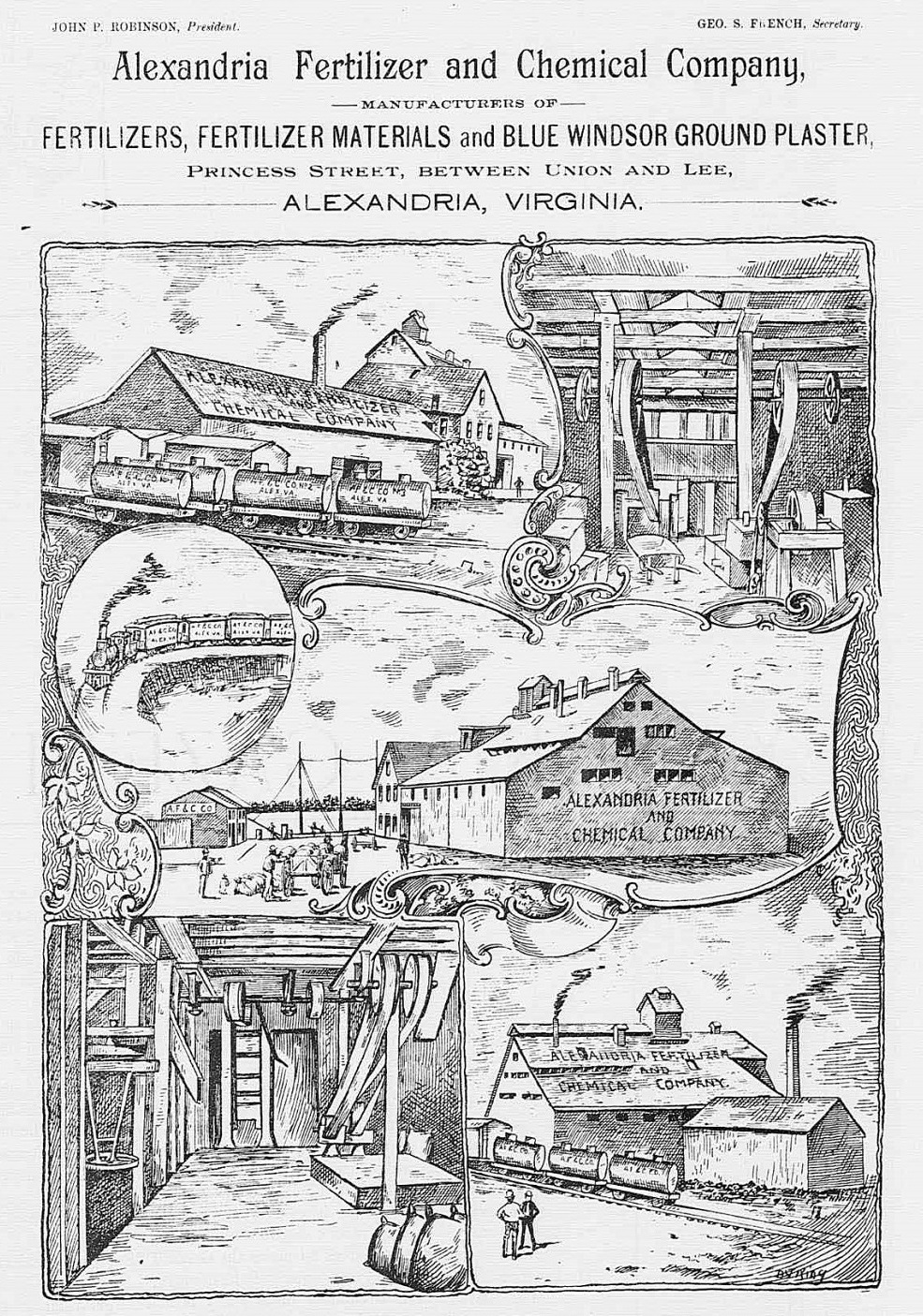

Alexandria’s rapid industrialization after the Civil War provided new job opportunities for African American men. One of the largest industries was fertilizer, which emerged in response to the exhaustion of soils by farmers in the Chesapeake region. Prior to the Civil War, William H. Fowle had imported guano from South America, a common method to augment poor soils, and sold it to local farmers. [36] In 1873, Herbert Bryant, another wealthy white resident, owned the city’s first fertilizer plant, which made use of animal bone. His facility was originally located at the foot of Queen Street. By 1892, Bryant moved his plant to the intersections of Duke and Union Streets where he had access to his crib wharf. [37] In the late 19th century, a new method using phosphate rock, which was abundant in the Deep South, emerged as a more effective alternative to make fertilizer. As a result, a group of white entrepreneurs established the Alexandria Fertilizer and Chemical Company in 1889, the city’s first phosphate rock plant, on Princess Street between Lee and Union Streets. [38] By 1899, the Washington Post reported that this plant was “one of the largest and strongest concerns operating in the South.” [39]

The work, which involved the smelting of phosphate rock and mixing it with chemicals, was dirty and dangerous, and most white men avoided it. In 1900, a fire broke out, causing $10,000 worth of damage. Luckily, a newly installed firewall protected most of the facility, including its notorious acid tanks. [40] Sometimes, residents objected to the smells from the plant, especially during the hot summer months. The company recognized the problem, and, in 1916, hoped that two new concrete dens for dissolving phosphate rock would contain the smell. [41] In at least one instance, the work proved deadly. In 1913, a pile of phosphate rock slid and killed one African American employee and injured two others. [42]

In the years leading up to World War I, some African American workers left Alexandria’s fertilizer plants and migrated north to Pennsylvania where they found jobs in the steel industry. The wages were better, and the state had no Jim Crow laws. Fertilizer plant owners bitterly complained, and Alexandria’s City Council tried to bar northern companies from recruiting local laborers. The law was not effective. Based on newspaper accounts, at least 700 African American workers left Alexandria during World War I for employment in the North. [43]

Because of the labor issues surrounding the production of fertilizer, African American workers at the American Agricultural Fertilizer Company (the Alexandria Fertilizer and Chemical Company changed its name in 1922 after it was bought out) attempted to unionize. [44] In 1940, the company finally recognized the unionization of its African American workers who joined Local 764 of the International Hod Carriers’ Building and Common Laborers’ Union (also known as the Laborers’ Union), an affiliate of the American Federation of Laborers (AFL). Unlike other organizations, the Laborers’ Union promoted the rights of African American workers, especially in the American South, during the 1930s and actively sought to recruit them. By 1941, it passed resolutions at the union’s annual convention openly criticizing the defense industries for discriminating against African American workers, and declaring that the “future of democracies depends largely upon strictly respecting the principle that the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is applicable to all, irrespective of race, creed, or color.” [45]

During World War II, the Laborers’ Union, like other affiliates of the AFL, agreed to avoid any work stoppages that might negatively impact wartime mobilization. The federal government also established the National War Labor Board to mediate any disputes. In the meantime, Local 764 at the American Agricultural Fertilizer Company struggled to maintain its membership; however, those who participated wanted to improve the work conditions for its members. They were concerned not only with low wages and the company’s vacation plan, but also hoped to make it a closed shop to protect employees from a potential flood of workers after the war. On August 1, 1944, fifty-nine employees, all African American, did not report to work and stayed away from the plant for almost ten days. [46] The American Agricultural Chemical Company turned to the National War Labor Board to intervene on its behalf. The Board, upon review of the record, recognized that the plant’s African American workers received wages far below other workers in the region, and recommended that a wage increase be granted. Neither the National War Labor Board nor the American Agricultural Chemical Company would agree to a closed shop, which would not only limit recruitment but also undermine the Virginia Public Assemblages Act (1926), which required the segregation of all public spaces. [47] White workers, who operated the machinist shop separate from the dangerous work with the phosphate rock, refused to participate in the strike. [48] The strike ended in fall of 1944, and was a partial victory for Alexandria’s African American workers who won an increase in their wages.

Stop 7: West's Point

Foot of Oronoco Street

18th Century

Seventeen years before Alexandria was founded in 1749, Virginia established a tobacco inspection station to ensure the colony shipped only good quality tobacco on what would become known as West’s Point. Previously, planters had packed barrels with their best tobacco on top and inferior tobacco or even oak or maple leaves on the bottom. As a result, Virginia tobacco had acquired a bad name for itself in British and other European markets. Thus, the colony established tobacco inspection stations at privately owned warehouses on local waterways to ensure the quality of Virginia’s tobacco. [49]

At the warehouse, tobacco inspectors evaluated the tobacco, and planters rented space to store it. To transport tobacco to the inspection station, enslaved workers packed the leaves into huge barrels, four feet tall and two and a half feet in diameter called “hogsheads.” A full hogshead could weigh up to 1,400 pounds. [50]

Enslaved African Americans manually rolled or carted the huge and heavy hogsheads to the station. To get to the station at West’s Point, enslaved men rolled the hogsheads along a road that ran from Virginia’s interior diagonally across what today are Alexandria streets and terminated at the station. After inspection, enslaved men loaded the hogsheads on ships sailing for Great Britain where they were sold and eventually reached the rest of Europe. [51]

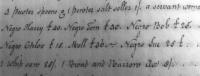

Between 1735 and 1738, Hugh West acquired the point and its warehouse. West owned several enslaved African Americans including Harry, Tom, and Bob, who probably did the hard work of his tobacco operation. [52] Realizing the potential of his new property, West also launched a ferry operation in 1740 across the Potomac River to Maryland, most likely run by enslaved men as well. [53]

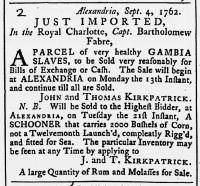

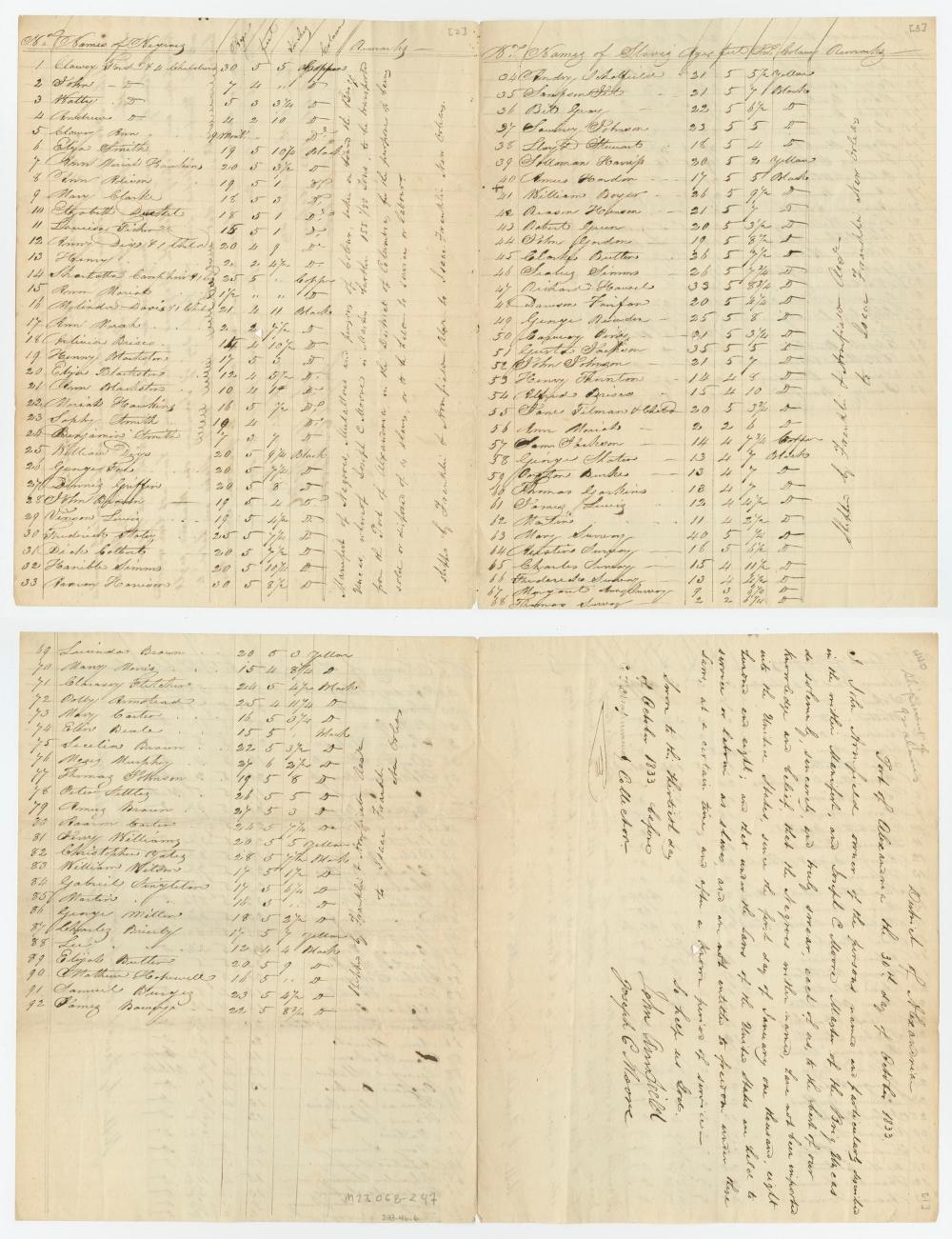

When Alexandria was established, West expanded the operations at his point to include a tavern. Chloe, Molly, and Sue, also owned by West, might have done the tavern’s washing, cleaning, and cooking. West managed this small business enterprise until his death in 1754. In his estate’s property inventory, Harry was valued at 40 pounds sterling, Tom at 40 pounds, Bob at 25, Chloe at 15, Moll at 36, and Sue at 25. [54] Slave owners derived these monetary values based on sex, age, skills, and other physical characteristics, often viewing adult males at the highest value. These numbers highlight how slave owners treated African Americans as property instead of human beings. Historical documents rarely if ever note how enslaved people gave meaning and non-monetary value to their own lives.

Stop 8: African American Neighborhoods

Oronoco Bay North

Trail Sign: African American Neighborhoods

19th Century

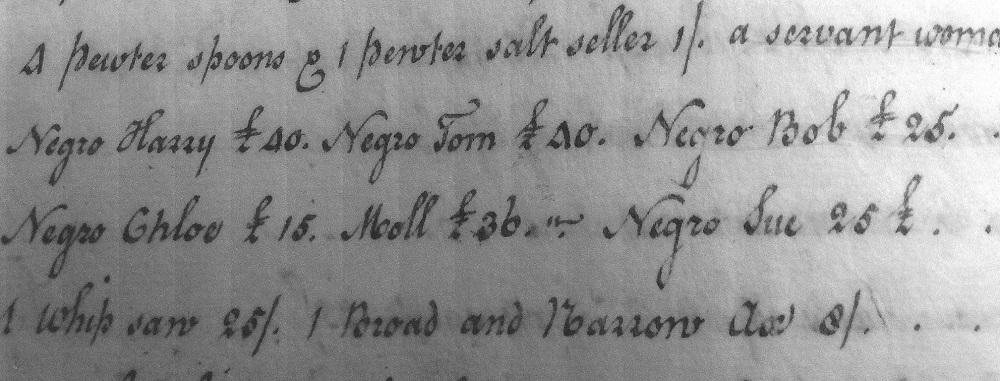

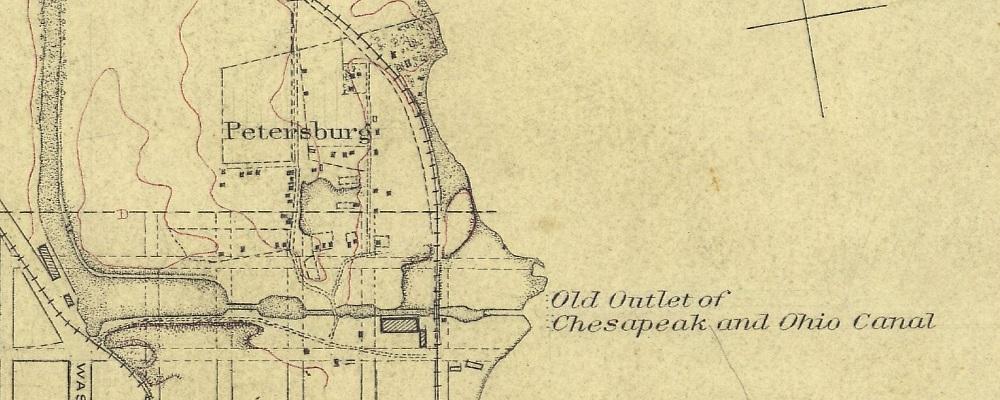

Three African American neighborhoods straddled Oronoco Bay, just off the river’s edge—what became known as The Berg and Fishtown to the south and west and Cross Canal to the north. Community names reflected the areas that enslaved people fled from during the Civil War to Union-occupied Alexandria, characteristics of their new settlements, or recognition of those who supported the cause of freedom. These names, however, were also in flux, and reflected the flows of African American refugees in and out of the city along with Alexandria’s racial politics. One 1864 reporter recounted, “We have ‘Petersburg,’ and ‘Richmond,’ ‘Contraband Valley,’ and ‘Pump Town,’ and twenty other towns in our midst.” [55]

During the war, “Grantville” and “Petersburg” came to identify roughly the same area in this part of the city. Historic records attribute the name Grantville to two people: General Ulysses S. Grant, who led Union forces during the last few years of the war, and Peter Grant, a shoemaker said to have built the first house in the neighborhood for a cost of $39. [56] The community name, recognizing both Grants, was said to have “kill[ed] two birds with one stone.” [57] In 1863, Julia Wilbur wrote in a letter that “Grantville numbers about 100 houses now, & they are building a school house too.” [58]

Petersburg, shortened to “The Berg,” alluded to the area in Virginia from which many of the refugees had fled, notably a location of intense fighting during the war. A 1982 oral history interview with long-time resident of The Berg, Henry Johnson corroborated the derivation of the neighborhood’s name from the city in Southside Virginia. [59]

After the Civil War, the name Grantville disappeared from the written historical record, to be replaced by The Berg. Although we have no documentation as to why this change happened, we can speculate that the city’s white elites, who returned to Alexandria after the war, did not support having any neighborhoods named after a self-emancipated African American or a Union general. African American residents, however, could have also decided to change the name to better reflect the community.

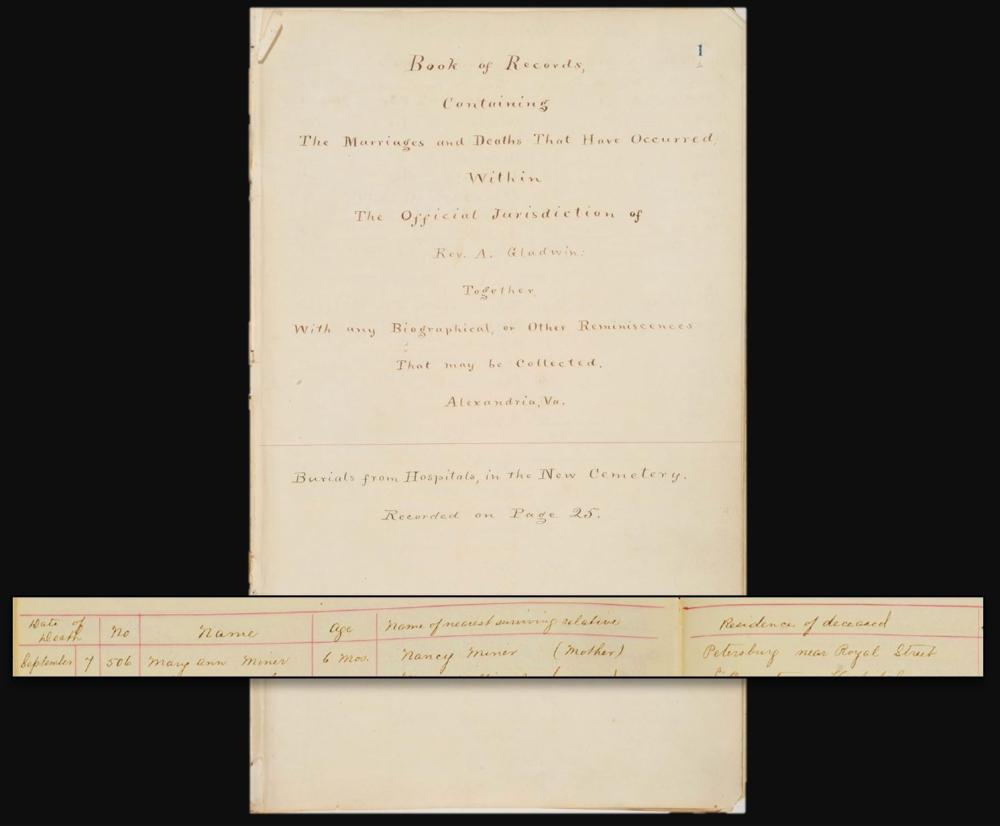

Evidence for the shift in naming practices during and after the Civil War comes from the Book of Records, primarily kept by Superintendent of Contrabands, Reverend Albert Gladwin, who documented those buried in the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery on South Washington Street. [60] Gladwin, in addition to recording names, dates of death, and ages also recorded the residence or place of death. After September 1865, Grantville disappeared from his records, while Petersburg appeared on a regular basis after December 1865.

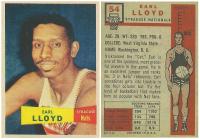

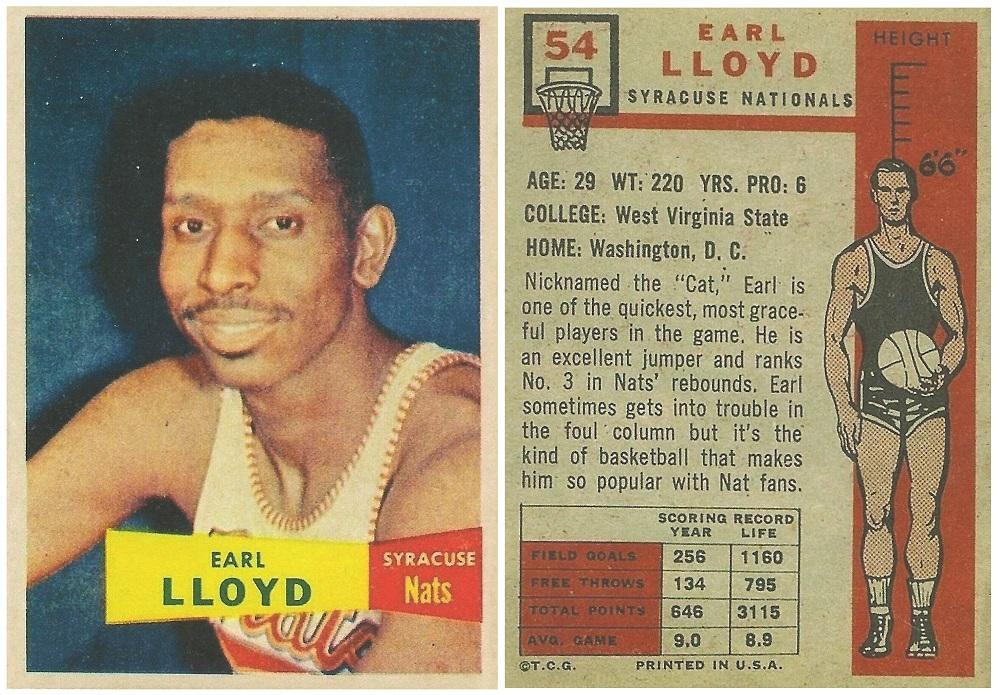

Residents of The Berg included twentieth-century luminaries like Earl Lloyd, the first African American to play in the National Basketball Association (NBA), breaking the color barrier on October 31, 1950. Born in 1928 in Alexandria and raised in The Berg, Lloyd graduated from Parker-Gray High School (today, the location of Charles Houston Recreation Center on Wythe Street across from the Alexandria Black History Museum), and received a scholarship to play in college before entering the NBA. Lloyd was also the first African American to become an assistant coach in the NBA. [61]

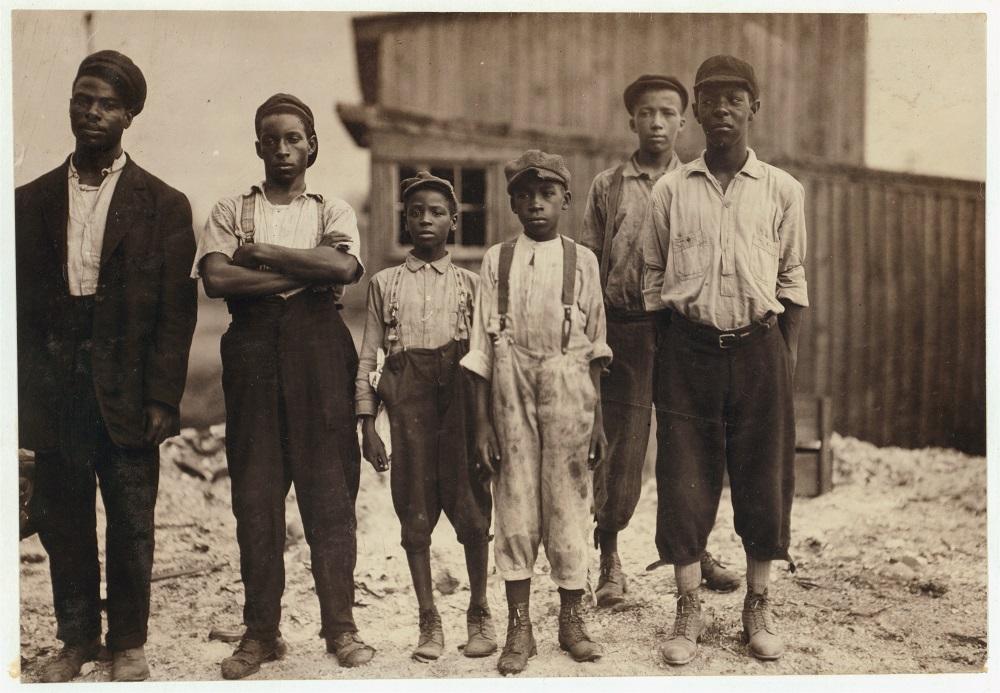

Stop 9: The Canal and Laboring at the Coal Wharf

Canal Tide Lock

19th Century

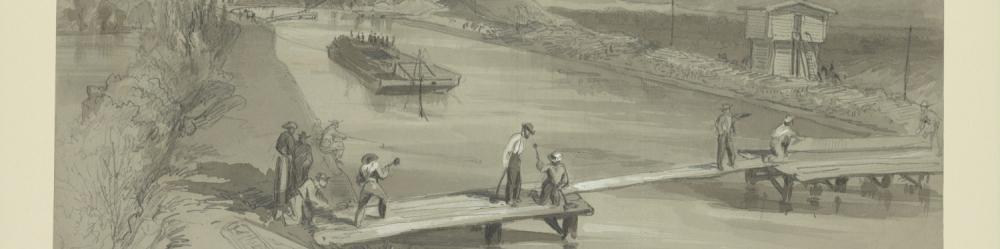

At this site is a reconstruction of the tide or end lock of the Alexandria Canal – the canal that once stretched from Alexandria seven miles north to present-day Rosslyn, Virginia. There, it crossed the Potomac River on a water-filled aqueduct, the abutments of which can still be seen adjacent to the Francis Scott Key Bridge that connects Rosslyn to Georgetown in the District of Columbia. From there, the Alexandria Canal connected to the much longer Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O Canal) and allowed finished goods, raw materials, and agricultural commodities to flow up and down the canals from Maryland and points west. [62]

The aqueduct and canal were constructed from 1832 to 1843, probably with the labor of enslaved African Americans. Work finished two years later in 1845 when the canal was finally connected to the river with the completion of four locks descending from Pitt Street, four blocks to the west from the end lock replica. The canal was beneficial to Alexandria's economy, but faced stiff competition from the growing railroads. [63]

Building the aqueduct particularly required a large quantity of timber, and an enslaved black man named George Henry brought some of that timber to Georgetown. Henry had the rare responsibility for an enslaved man of captaining a schooner, the Llewelyn, belonging to Alexandrian Sally W. Griffith. He sailed the Llewelyn, loaded with heavy oak trees 45-to-50 feet long, from a wooded site down the Potomac to the aqueduct construction site where other enslaved men likely unloaded the timber and built the aqueduct. [64]

Moreover, a hundred years earlier, another enslaved African American man helped open land for settlement beyond the future C&O Canal in western Pennsylvania and Ohio. He accompanied a North Carolinian named Christopher Gist in a journey by horseback lasting five and a half months, from late 1750 to spring 1751. Their task was to investigate the area for the Ohio Company, a land development company, a third of whose organizers were among the first purchasers of lots in Alexandria. Part of the company’s goal was to open up this new land for settlers who would trade with the new Potomac River town of Alexandria. [65]

It would have been an unusual adventure for an African American man (his name was never recorded), traveling from western Maryland, where he and Gist started, almost as far west as present-day Louisville, Kentucky, and then returning to western North Carolina. Along the way, he and Gist traveled with a métis guide, who spoke French, English, and several tribal languages. The enslaved man also stayed alone in a Shawnee camp for over three weeks tending the two’s horses; meeting an enslaved black man who belongs to an Indian leader; and handling a mammoth’s tooth weighing “better than four pounds” found in the fossil-rich area at the Falls of the Ohio River. [66]

Taking goods to and from the west by horseback and wagon load, however, was not satisfactory—thus, the canal. It operated successfully until May 1861, when federal troops occupied Alexandria. Federal authorities considered the canal’s aqueduct more useful as a bridge to move troops and military supplies across the Potomac River into Virginia, so they cut off water to the aqueduct and covered it with planks. As a result, goods flowed down the canal to Georgetown but not to Alexandria. [67]

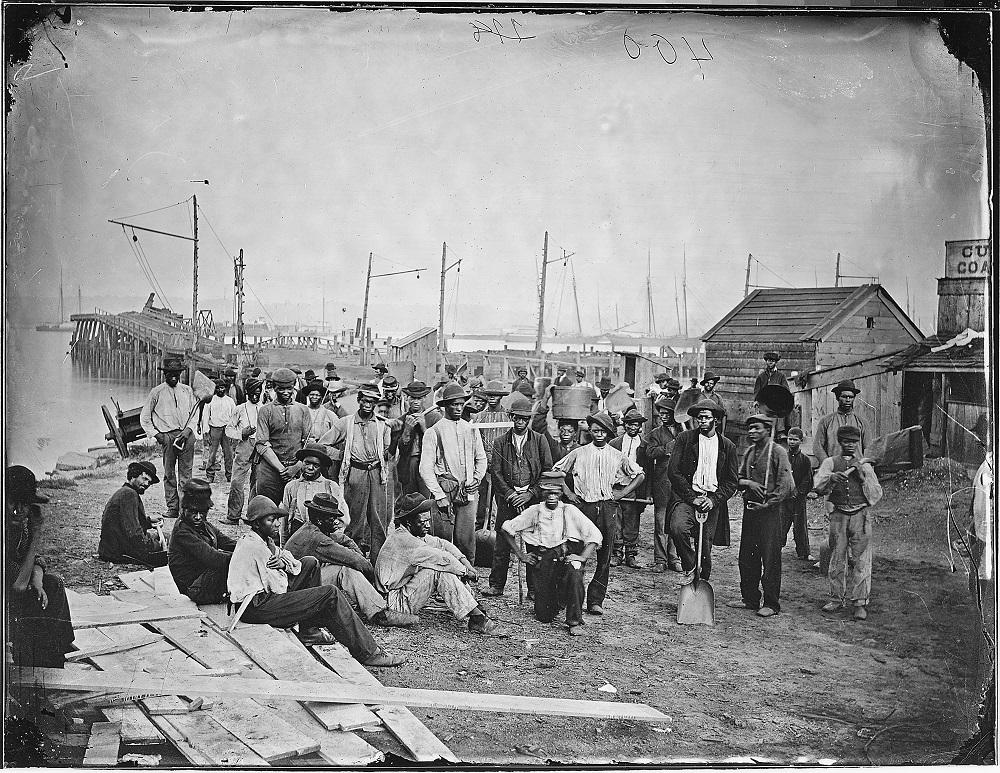

During the Civil War, many African American men who had escaped from slavery or who were already free worked on the Alexandria waterfront loading and unloading ships, building structures, and shoveling coal. A photograph taken during the war shows African American men standing and sitting next to the canal and in front of the old coal wharf, then used by the Union Quartermaster Corps. Several hold shovels indicating they are doing some sort of labor, probably shoveling coal. (Coal dust is visible on some of their clothing, particularly on the man in a white shirt and pants sitting in front.) [68]

The canal operated until 1886, with the continued help of African Americans, now free. After the canal shut down, it was gradually filled in. Its route now lies under buildings, streets, and shopping malls in Arlington and Alexandria. [69]

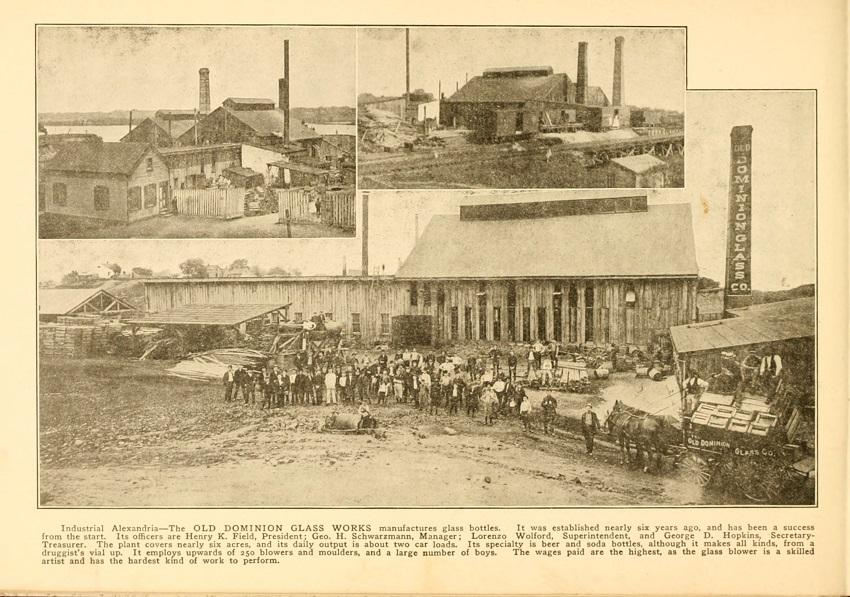

Stop 10: Old Dominion Glass Corporation

Foot of Montgomery Street

20th Century

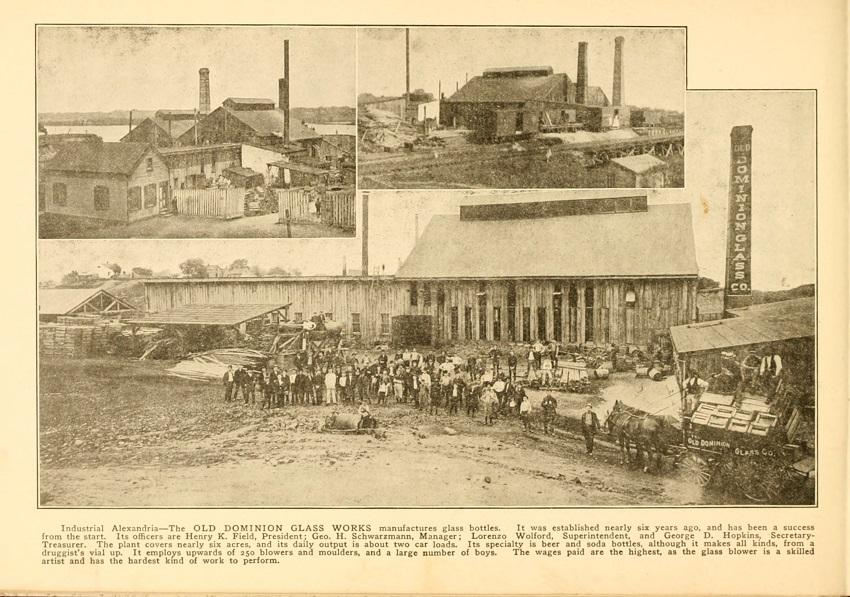

The Old Dominion Glass Corporation’s factory was located near the waterfront, on the north side of Montgomery Street between Lee and Fairfax Streets. It began operation around 1902 and by 1920 it employed 250 people, including teenagers, a controversial practice in early twentieth-century United States. Young African Americans, like 13-year-old Charles Taylor, 17-year-old Abraham Lomax, Jr., 15-year-old Lawrence Dawkins, 16-year-old Lloyd Montgomery Arnold, and 14-year-old Henry Anderson, worked at this glass factory or others in Alexandria. [70]

If around 1911 you were a boy as young as 10 years old, white or African American, you might have worked in a large factory on the Alexandria waterfront that produced glass beer, soda, and medicine bottles. The work was nine hours a day—four and half hours on your station, a one-hour break, and then a final four and a half hours until quitting time. If you were on the day shift, your work started at 7:00 a.m. and stopped at 5:00 p.m. If you were on the night shift, you began work at 6:00 p.m. and ended at 4:00 a.m. If you worked a day shift one week, the next week you worked nights. The pay probably would have been no more than ten cents an hour. A few girls between the ages of 12 and 18, both African American and white, also worked at the factory, stationed primarily in the packing department. They were paid even less. The factory melted glass ingredients in its furnaces 24-hours-a-day, except for July and August when the combination of hot weather and hot furnaces made work too difficult. As a boy, your work would have been in the glass-blowing room near the oven’s continuous flames and intense heat (between 2,460-2,920 ℉). [71]

In 1982, an African American woman who worked at the factory, Virginia Knapper, described part of the glass-making process: the molten glass in the furnace “was runny . . . more like the dough you make pancakes from.” A man stuck a long rod into the furnace and into the molten glass. Then he wound the rod around until he got a certain amount of the doughy glass onto it. He then took the rod out and “rolled it up and down, up and down and there’d be two of us sitting at the molds” where the doughy glass was inserted. Knapper recalled: “I was a snapper: when it came out of the mold, I’d be there with my gadget and snap it off.” [72]

In 1911, Lewis Hines, photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), visited several glass factories in Alexandria to document the working conditions faced by children as young as 10 or 11 years old. The boys pictured here worked at the Alexandria Glass Factory, located about eight blocks west of here, also on Montgomery Street. [73]

Because the factory was built of wood and its furnaces were fired continuously, it was susceptible to fires. In February 1902, soon after the factory opened, a fire ravaged the Old Dominion Glass Corporation. The Alexandria Gazette reported that fire engines “after much difficulty in forcing their way through snow and mud reached the scene of the fire, but it was impossible to check the flames and in less than two hours nothing remained but the brick smoke chimney and a heap of ashes.” Because of the fires, coal shortages, and Prohibition (which severely reduced the demand for beer and wine bottles), the Old Dominion Glass Company closed in 1925. [74]

In a brief rescue excavation before a hotel was built on the site in 1972, archaeologists recovered glass working tools such as shears, tongs, a blow pipe, gauges and pieces of glass molds. Many examples of wasters – misshapen bottles and pieces of decorative glass canes – were also found, including beer bottles for the nearby Portner’s Brewery. Many of the bottles were marked "OD" [Old Dominion] on their bases. [75]

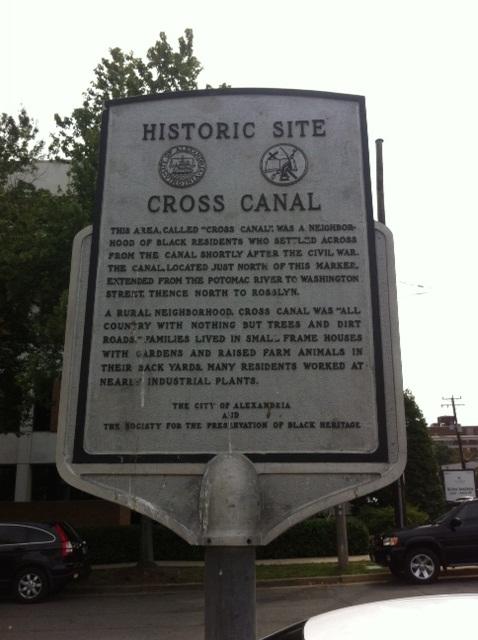

Stop 11: Cross Canal

Intersection of Montgomery and North Fairfax streets

19th Century

“Ever since I can remember, it was called Cross Canal.” Virginia Knapper’s oral history, recorded by Alexandria Archaeology in 1982, remains one of the best sources of information on the Cross Canal neighborhood. Knapper was born in 1897 in a house located on North Fairfax Street. In her oral history, she recalls memories of the Cross Canal neighborhood, and she describes the canal, its respective bridges, locks, and the general landscape in the vicinity. Knapper also depicts a neighborhood, filled with gardens and fruit trees of all kinds, and dirt paths and roads, distinctly different from the more developed city to the south. [76]

The Cross Canal neighborhood was a quiet rural area before and during the Civil War, later named after the war for its position just across the Alexandria Canal at the northeast tip of the city. Barges moved cargoes of grain, whiskey, lumber, or coal through the canal locks along First Street from 1843 until the canal closed in 1886. African Americans may have moved to Cross Canal in search of affordable housing, or to be close to jobs at the wharves. Some worked at local factories, such as the Old Dominion Glass Factory, including Virginia Knapper. The Cross Canal area centers around the 800 block of North Fairfax Street between Montgomery and First Streets, bordered on the western side by South Royal Street. None of the structures from the turn of the century still stand.

Conclusion

Although this is the end of this trail, the stories we have to tell about Alexandria’s African American history are innumerable and span from the river’s edge to the west side of the city.

For more information on the history of Alexandria’s African American community, visit the Alexandria Black History Museum, the Alexandria Archaeology Museum, the Freedom House Museum, Alexandria African American Heritage Park, Contraband and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial, Fort Ward Museum and Historic Site, and the Charles Houston Recreation Center.

Footnotes

Footnotes

[ 1] Belinda Blomberg, Free Black Adaptive Responses to the Antebellum Urban Environment: Neighborhood Formation and Socioeconomic Stratification in Alexandria, Virginia 1790-1850 (PhD diss., American University, 1988).

[ 2] Daniel Kryder, Divided Arsenal: Race and the American State during World War II (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[ 3] “Ex-Mach. Div. Employee Graduates at Nashville,” The Torp (Alexandria, VA), 4, no. 1 (Aug. 1945): 3.

[ 4] “I’m Fine; How are You?” The Torp (Alexandria, VA) 3, no. 9 (Feb. 1945): 4; “Four Employees Receive Letters of Commendation,” ERA News (Alexandria, VA) 1, no. 5 (Sept. 1947): 6.

[ 5] Seymour J. Pomrenze, “Policies and Procedures for the Protection, Use, and Return of Captured German Records,” Captured German and Related Records: A National Archives Conference, ed. Robert Wolfe (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1974), 6-30; Robert Wolfe, “The National Archives: Center for Captured German and Related Records,” Captured German and Related Records: A National Archives Conference, ed. by Robert Wolfe (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1974), 223-228.

[ 6] Pamela Cressey, “Early Wharf Remains Show Changed Shape of Waterfront,” Alexandria Gazette Packet, June 2, 1994; accessed January 6, 2020.

[ 7] George E. O’Malley, Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807 (Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and the University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 291-292.

[ 8] Donald M. Sweig, “The Importation of African Slaves to the Potomac River, 1732-1772,” The William and Mary Quarterly 42, no. 4 (October 1985): 514-520.

[ 9] [Advertisement], Maryland Gazette 9 Sept. 1762, 2; [Advertisement], Maryland Gazette 4 Aug. 1763, 3; [Advertisement], Maryland Gazette 10 Oct. 1765, 2.

[ 10] Leonardo Marques, The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas, 1776-1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 16-18.

[ 11]“An Act for the cession of ten miles square, or any lesser quantity of Territory within this State, to the United States, in Congress assembled, for the permanent seat of the General Government,” in Andrew Rothwell, Laws of the Corporation of the City of Washington (Washington, D.C.: F. W. DeKraft, 1833), 363-364.

[ 12] “An Act to amend an act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States,” 1st Congress, Third Session, Chapter XVII (1790); Bob Arnebeck, Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800 (Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 1991), 33-34.

[ 13] A. Glenn Crothers, “The 1846 Retrocession of Alexandria: Protecting Slavery and the Slave Trade in the District of Columbia,” in In the Shadow of Freedom: The Politics of Slavery in the National Capital, ed. Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press: 2011), 144-146.

[ 14] Ibid, 146-147, 150.

[ 15] Crothers, 148-162; Mark David Richards, “The Debate over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801-2004,” Washington History 16, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2004), 59-67. Both Crothers and Richards seem to have gotten the vote total for Alexandria wrong. Richards has the total for both Alexandria and the surrounding county as 537 for and 155 against (pg. 67). Crothers has the total in Alexandria as 606 for and 211 against (pg. 148).

[ 16] William Jay, Miscellaneous Writings on Slavery (Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co., 1853), 153.

[ 17] Crothers, 142-143, 156, 157, 161-162; Constance McLaughlin Greene. Washington: Village and Capitol, 1800-1878 (Princeton: Princeton University Press: 1962) 95-98, 140, 143, 175.

[ 18] “An Act to retrocede the County of Alexandria, in the District of Columbia, to the State of Virginia,” 29th Congress, First Session, Chapter 35 (1846); Crothers, 142-143, 162-167; Richards, 67-71.

[ 19] Crothers, 141-142; Richards, 71.

[ 20] Richards, 73.

[ 21] Crothers, 166-167; Richards, 71-72.

[ 22] Crothers, 167.

[ 23] Crothers, 167; Richards, 74.

[ 24] "Local Items," Alexandria Gazette, 19 Apr. 1860, 3.

[ 25] "Local Items." Alexandria Gazette, 12 May 1860, 3.

[ 26] Ibid.

[ 27] "Local Items," Alexandria Gazette, 19 Apr. 1860, 3.

[ 28] The Charter and Laws, of The City of Alexandria, VA., and an Historical Sketch of its Government, City Council, Alexandria, Virginia, 1874; "Fishwharf Property," Alexandria Gazette, 27 Feb. 1913, 2.

[ 29] "Local Matters," Alexandria Gazette, 1 Mar. 1904, 4; “Fish Wharf," Alexandria Gazette, 1 Aug. 1842, 3.

[ 30] “News Article,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 6 Apr 1857, 4.

[ 31] “News Article, Local News,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 30 Oct. 1861, 2.

[ 32] "Local Items," Alexandria Gazette, 19 Apr. 1860, 3; "Local Items," Alexandria Gazette, 17 Mar. 1859, 3.

[ 33] "Local Items," Alexandria Gazette, 19 Apr. 1860, 3.

[ 34] Robert H. Dogan, Claim Number 48709, 5 Dec. 1877, Alexandria, VA; Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims, 1871-1880: Virginia (Microfilm Publication M2094, roll 2); Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group 217; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[ 35] "News Article," Alexandria Gazette, 2 May 1913, 3.

[ 36] Paul Wallace Gates, The Farmer’s Age: Agriculture, 1815-1860, The Economic History of the United States, vol. 3 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960), 108; Harold W. Hurst, Alexandria on the Potomac: The Portrait of an Antebellum Community (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1991), 12; Shepherd W. McKinley, Stinking Stones and Rocks of Gold: Phosphate, Fertilizer, and Industrialization on Postbellum South Carolina (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016), 16-17.

[ 37] [Advertisement] “Herbert Bryant, Manufacturer of Fertilizers,” Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, 16 Sept. 1893, 17, supplementary edition.

[ 38] “Alexandria,” Washington Post, 4 March 1889, 8.

[ 39] “Alexandria News in Brief,” Washington Post, 17 March 17 1899, 8.

[ 40] “Alexandria News in Brief,” Washington Post, 19 Aug. 1900, 5.

[ 41] “Improving Fertilizer Plant: Alexandria Concern Hopes to Banish Disagreeable Acid Odors,” Washington Post, 19 July 1916, 3.

[ 42] “Seats in Doubt until June,” Washington Post, March 24, 1913, 12.

[ 43] “Negros Lured North,” Alexandria Gazette 28 Aug. 1916, 3; “Big Plants Lack labor,” Washington Post, 13 Nov. 1916, 7; “Big Plants Lack Labor,” Washington Post, 13 Nov. 1916, 7; “An Ordinance to Regulate the Employment of Persons for Service or Labor Outside of the State of Virginia,” Alexandria Gazette, 30 May 1917, 3.

[ 44] “500 Lights Flash Alexandria’s Fifth Trade Show Opening,” Washington Post, 8 April 1924, 10.

[ 45] Report of Proceedings of the Eighth Convention International Hod Carriers’, Building & Common Laborers’ Union of America (St. Louis: September 15-19, 1941), 471, 480, 523, 680.

[ 46] “Alexandria Plant Still Strikebound,” Washington Post, 9 Aug. 1944, 7; “2 D.C. Area Strikes End After Federal Agencies Intercede,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), 10 Aug. 1944, 17; “Strike is Ended at Alexandria,” Washington Post 10 Aug. 1944, 4.

[ 47] In the Matter of American Agricultural Chemical Company (Alexandria, Virginia), and Building Supply and Material Yard Union, Local No. 764 of the International Hod Carriers’ Building and Common Laborers’ Union of America, AFL June-Oct. 1944; Record Group 202, National Archives, Atlanta, GA.

[ 48] “50 on Strike Again over Pay WLB Refused,” Washington Post 1 Oct. 1944, M5.

[ 49] William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, form the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, vol. 4 (New York: R. & .W. & G. Bartow, 1823), 247-271, 331.

[ 50] Arthur Pierce Middleton, Tobacco Coast: A Maritime History of Chesapeake Bay in the Colonial Era, ed. for Mason George Carrington (Newport News, VA: Mariners’ Museum, 1953), 100-102, 123-125.

[ 51] Cartouche from 1755 Fry-Jefferson Map above; James Bish, “Forgotten Friends of Washington and Mason: The West Family and Their Momentous Role in the Founding and Development of Alexandria, Fairfax County, and Loudoun County, Virginia” (Alexandria, VA: Alexandria Archaeology Office, n.d.), 6.

[ 52] James Bish, “Chronology of Hugh West Primary Sources” (Alexandria, VA: Alexandria Archaeology Office, n.d.), 2-3; Fairfax County Will Book B-1 (Fairfax, VA: Fairfax County Circuit Court’s Historical Records Room), 74-75, 77-78.

[ 53] Bish, “Forgotten Friends,” 6.

[ 54] Bish, “Forgotten Friends,” 14; Fairfax County Will Book B-1 (Fairfax County Circuit Court’s Historical Records Room, Fairfax, VA), 74-75, 77-78.

[ 55] “Alexandria Affairs,” Evening Union (Washington, D.C.), 26 August 1864, n.p.

[ 56] History of Schools for the Colored Population (1871 Reprint; New York: Arno Press, 1969), 290.

[ 57] History of Schools for the Colored Population, 291.

[ 58] Julia A. Wilbur to Anna M. C. Barnes, October 2, 1863, in The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, ed. Jean Fagan Yellin, Joseph M. Thomas, Kate Culkin, and Scott Korb, vol. 2 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2008), 510-518.

[ 59] Oral History interview with Henry Johnson, October 1, 1982. Interviewers Pamela Cressey, Elizabeth Clark-Lewis, and Steve Anderson. On file Alexandria Archaeology.

[ 60] Wesley E. Pippenger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records, 1863-1869 (The Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896 (Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications, 1995).

[ 61] Earl Lloyd and Sean Kirst, Moonfixer: The Basketball Journey of Early Lloyd (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010).

[ 62] Thomas Swiftwater Hahn and Emory L. Kemp, The Alexandria Canal: Its History and Preservation (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 1992).

[ 63] Ibid.

[ 64] George Henry, Life of George Henry Together with a Brief History of the Colored People of America (Providence: H. I. Gould & Company, 1894); accessed January 6, 2020.

[ 65] William M. Darlington, Christopher Gist’s Journals (Pittsburgh: J. R. Weldin & Co., 1893), 31-60; Lois Mulkearn, ed., George Mercer Papers Relating to the Ohio Company of Virginia (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1954), 2-3; William Francis Smith and T. Michael Miller, A Seaport Saga: Portrait of Old Alexandria, Virginia (Virginia Beach: The Donning Company Publishers, 2001), 17.

[ 66] William M. Darlington, Christopher Gist’s Journals (Pittsburgh: J. R. Weldin & Co., 1893), 31-60.

[ 67] Ames W. Williams, “Transportation,” in Alexandria: A Towne in Transition, 1800-1900, ed. John D. Macoll (Alexandria: Alexandria Bicentennial Commission, 1977), 55; Anna Maas, “901 N. Fairfax St. Historic Interpretation Plan,” (Gainesville, VA: Thunderbird Archaeology, 2018), 9.

[ 68] Amy Murrell Taylor, Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 28; Chandra Manning, Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (New York: Vintage Books, 2017), 47.

[ 69] T. Michael Miller, ed., Pen Portraits of Alexandria, Virginia, 1739-1900 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1987), 340-341; Thomas Swiftwater Hahn and Emory L. Kemp, The Alexandria Canal: Its History and Preservation (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 1992).

[ 70] Char McCargo Bah, “The Other Alexandria: Working in the City’s Glass Factories,” The Connection (Alexandria, VA), February 5, 2019; accessed April 21, 2020.

[ 71] Johnna Flahive and Boyd Sipe, “Documentary Study of the 800 Block of North Henry Street, Alexandria, Virginia” (Gainesville, Virginia: Thunderbird Archaeology, 2006), 13-16. 26; Anna Maas, “901 N. Fairfax St. Historic Interpretation Plan” (Gainesville, Virginia: Thunderbird Archaeology, 2018), 12; Martha J. Merselis, “An Ale from Alexandria: Glassblowers at the Old Company” (undergraduate paper, George Washington University, American Civilization, 1991), 1, 7.

[ 72] Virginia Knapper, interview by Pamela Cressey, transcription, March 24, 1982, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, Virginia, accessed on August 31, 2020.

[ 73] Anna Maas, “901 N. Fairfax St. Historic Interpretation Plan” (Gainesville, VA: Thunderbird Archaeology, 2018), 12.

[ 74] T. Michael Miller, “Alexandria’s Crystal Palaces,” The Fireside Sentinel, 5, no. 11 (Nov. 1991): 139-141; Maas, n.p.; Merselis, n.p.

[ 75] Knapper interview; T. Michael Miller, "Alexandria's Chrystal Palaces," 137; Flahive and Sipe, n.p.; Maas, n.p.; Merselis, n.p.

[ 76] Unalane Ablondi, interview by Jennifer Hembree, transcription, June 30, 2007; Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, accessed on January 6, 2020.