Aboard Ship with the Jack-Tars of the Union Navy

Aboard Ship with the Jack-Tars of the Union Navy

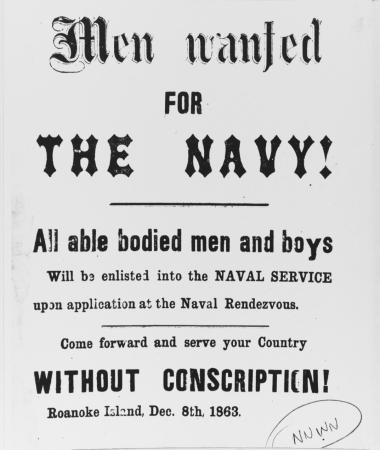

The United States Navy underwent a massive and rapid expansion in both fleet and crew during the Civil War. To patrol the 3,500 miles of Confederate coastline as part of the Union blockade and secure the South’s major inland waterways, the U.S. Navy recruited over 50,000 sailors, or “jack-tars”, to man more than 600 ships. By the end of the war in 1865, it became the world’s largest naval force and a key factor in the North’s eventual victory.

This exhibit uses objects from Fort Ward Museum’s Civil War naval collection to explore sailor’s lives, from their uniforms to the way they communicated, navigated, and defended the ship. The exhibit also highlights Commander James Harmon Ward, Fort Ward’s namesake and the first naval officer to die in the Civil War, as well as rare objects and souvenirs collected by both sailors and civilians.

Opening to coincide with the U.S. Navy’s 250th anniversary in October 2025, the exhibit will continue through 2026.

Dressing By Rank

The uniforms of the U.S. Navy during the Civil War served to identify men based on their rank and roles aboard ship. The enlisted sailor wore a dark blue wool jumper with a wide, square-cut collar, often trimmed with white piping and a black silk neckerchief. The uniform also included bell-bottom trousers and dark blue wool cap that featured a ribbon with the vessel’s name. Summer dress meant sailors switched to a white canvas jumper, trousers trimmed in blue denim, and wide-brimmed straw hat.

Officers followed a more formal dress code that included a double-breasted frock coat with two rows of buttons. A combination of a specific number of gold lace stripes on their sleeves and insignia on their shoulder straps indicated rank.

Objects on View

- Canvas Gaiters

- Leather Belt with Brass Buckle, U.S. Navy Officer

- Petty Officer’s Cap, U.S. Navy

- Petty Officer Insignia Pattern, U.S. Navy

Ship-Wide Communication

Communication aboard a U.S. Navy vessel during the Civil War was designed to overcome the challenges of a large and noisy environment. The ship's bell served as the primary instrument for regulating the daily routine, with distinct tolls marking time and announcing a change in watch. For issuing commands, the boatswain's mate used a small, high-pitched whistle known as a boatswain's pipe to relay orders across the ship's deck. Despite the noise of the ship and the elements, a clear chain of verbal commands passed from the officer on deck down to the crew.

Sailors were also trained in a variety of signaling methods to communicate with other ships in the fleet or with shore stations. These included the use of signal flags, which were hoisted in specific combinations to convey coded messages, and semaphore, where a sailor used a pair of flags to represent letters of the alphabet. At night, signaling relied on colored lanterns or flashing lights, often following the same codes as the daytime flags.

Objects on View

- Wooden Alarm Rattle

- Oil Signal Lantern

- Gyroscopic Oil Signal Lantern

- U.S. Navy Signal Pistol, Model 1861, and Cartridge Box

Navigating the Waterways

For long-distance voyages, officers and trained navigators primarily used celestial navigation aboard ship. Sextants measured the angle of the sun, moon, or stars above the horizon, and with the aid of a nautical almanac and a chronometer, sailors could calculate the ship's latitude and longitude. Patrolling Confederate coastlines and rivers meant that a ship's position was frequently determined by visual cues and landmarks, relying on coastal charts to identify lighthouses, buoys, and topographical features.

Sometimes “dead reckoning” was needed to navigate. This involved estimating a ship's position based on its course and speed. A sailor would use a compass to maintain a consistent course and a log line to measure the vessel's speed. Constant vigilance was crucial, otherwise the ship risked running aground or being ambushed by shore batteries.

Objects on View

- Brass Sextant

- Magnetic Sextant in Wooden Case with Instructions

- Floating Compass in Wooden Case with Brass Oil Lantern

- Brass U.S. Navy Telescope

Defending the Ship

Ship-to-ship combat required larger artillery like the smoothbore Dahlgren which were specifically designed to handle the stress of firing heavy solid shot and explosive shells. Rifled guns like the Parrott also saw increased use as they provided greater accuracy and range. These large guns needed well-trained crews to transport the powder charges, load, aim, and fire.

Sailors were also equipped with a variety of small arms for close-quarters fighting and shore-based operations. For boarding actions, the cutlass’s short, curved blade and a boarding pike’s long reach provided a range of maneuverability based on the situation at hand. In on-shore engagements, landing parties were armed with carbines, rifles with bayonets, and pistols.

Objects on View

- Wooden U.S. Navy Practice Sword

- U.S. Navy Cutlass, Model 1860

- Savage-North Navy Percussion Revolver, .36 caliber

- Model 1861 Plymouth Rifle, .69 caliber

- Cartridge Box, U.S. Navy Revolver

- Boarding Axe

- Sword Bayonet for an Enfield Rifle

- Boarding Pike

- Naval Practice Battery, Navy Yard, Wash. D.C., woodcut engraving, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 21, 1861

What is a “Jack-Tar”?

“Jack-Tar” was a British nickname for a typical sailor. “Jack” referred to a workman (a “jack” of all trades). “Tar” has several possible origins. Some say it derived from the tarred pigtails that many British sailors sported. Other theories suggest how sailors sometimes tarred rigging to preserve it, or wore coats and hats made of tarpaulin, a waterproof fabric also used to cover deck hatches aboard ship.

Objects on View

- Oar

- Hymn Book for the Army and Navy published by the American Tract Society, 1861

- Copper Commemorative Token, 1864

- U.S. Navy Patriotic Envelopes

- “Pattern” Pass Box, Boston Navy Yard, 1864

- Memorial Marker

Fort Ward’s Namesake Cmdr. James Harmon Ward

Born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1806, Commander James Harmon Ward graduated from the American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy, and was commissioned as a midshipman in the Navy by the time he was 17 years old in 1823.

After serving aboard ships in the Mediterranean, West Indies, and off the coast of Africa, he became a master of ordnance and tactics, publishing three books by the end of his career. In 1845, he was named Executive Officer of the newly opened U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, which he helped found. For the next ten years, he served in the Mexican-American War, split his time between the Washington and Philadelphia Navy Yards, was promoted to Commander, and lead the African Squadron on the USS Jamestown.

During the Civil War, Cmdr. Ward drew up plans for a “light flying force” to patrol the Potomac River below Washington as part of President Lincoln’s strategy of blockading Southern ports. Ward commanded the newly formed Potomac Flotilla from the flagship USS Thomas Freeborn. The flotilla successfully bombarded Confederate batteries at Aquia Creek in May 1861 before moving to Mathias Point, about 50 miles south of Alexandria. On June 27, while sighting his bow gun aboard the Freeborn to provide cover for his retreating men, Cmdr. Ward was mortally wounded, becoming the first naval officer killed in the Civil War.

Objects on View

- A Manual of Naval Tactics by Commander James H. Ward, 1859

- Cmdr. James H. Ward, Hand-colored Lithograph

- The Body of Captain James H. Ward, hand-colored woodcut engraving, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 13, 1861

- Chapeau, U.S. Navy Officer

- Shoulder Knots, U.S. Navy Officer

- U.S. Navy Officer’s Sword and Sword Knot