A Segregated City

A Segregated City

From the 18th century on, neighborhoods in Alexandria were segregated by race and economic status. Free Black neighborhoods existed before emancipation. Still, these early neighborhoods like The Bottoms, Hayti, Fishtown, and later post-Civil War communities were always located in less desirable parts of town. Segregation forced African American residents to create their own communities, where they could worship, shop, attend school, and bury their dead. Segregation prevented races from meaningful interaction, making discrimination a part of life.

In the past, racial segregation was enforced by threats, intimidation, and in the extreme, lynching and other racial terror hate crimes. Later, restrictive covenants prevented those of a different race or religion from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. As recently as 2017, a study looking at the repercussions of segregation in Northern Virginia found “islands of disadvantage” that have led to poor health outcomes in those who experienced segregation and discrimination. Oral histories document the experiences and resilience of residents who lived in segregated Alexandria. Their work to change discrimination is carried on to new generations so that segregation remains in Alexandria’s past.

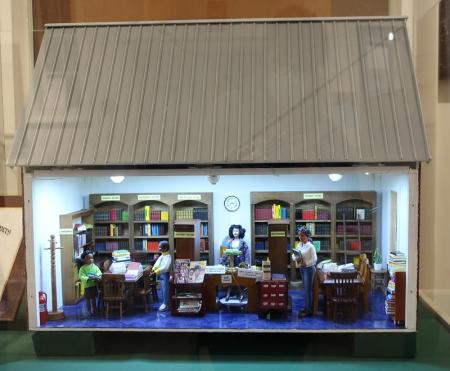

Alexandria Black History Museum.

Memories, from the Oral History Archive

Joyce Paige Abney, fifth-generation Alexandrian; interviewed by Logan Wiley, May 31, 2008:

When I grew up in Alexandria it was segregated, but I think it disturbed me because I was one of those curious children. I often asked ...why we couldn’t do certain things. Like go to the closest school. There were two schools that were two blocks from where we lived, but we had to walk several blocks to Lyles-Crouch. We had to cross Washington Street, which was a dangerous street. At that time, they did not have crossing guards, didn’t have stop lights, we had to cross that street.

I remember going with my grandmother to Murphy’s [variety store] and we couldn’t eat at the sit-down counter. You could stand at a counter on another side of the store, but not at the sit-down counter. I often questioned why we could not go to the other side of the store to sit down. I was told to lower my voice and to not ask so many questions...We couldn’t go to the white library, which was closer. I looked at it as an inconvenience and unfair.

We couldn’t go to the swimming pools; in fact, we didn’t have a swimming pool until I was a teenager. Some children drowned in the Potomac River and that was when they decided to build a pool for blacks. It was named in honor of two of the boys who had drowned.

Charles K. “Buster” Williams, born 1908; interviewed by Mitch Weinschenk, February 5, 1999:

Black and white didn’t go together. In the theaters, they had a partition. You saw the same picture, be in the same house. On one side of the wall were white and the other side black…It was terrible.

Beatrice Taylor, resident of Colored Rosemont; interviewed by Francesco De Salvatore, January 25, 2023:

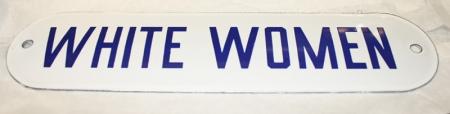

You get used to it [segregation]. You know where you can go and you know where you shouldn’t go. And our parents make sure we remember those things. If you were to go down on King Street and if you had to go to bathroom, they had segregated bathrooms and separate water things [fountains]. And if you wanted a hot dog, you had to stand up at the counter. If you wanted it, you could not sit down. But we knew all those things.

Courtney Brooks, born 1923; interviewed by Jim Mackay and Audrey Davis, November 15, 1996:

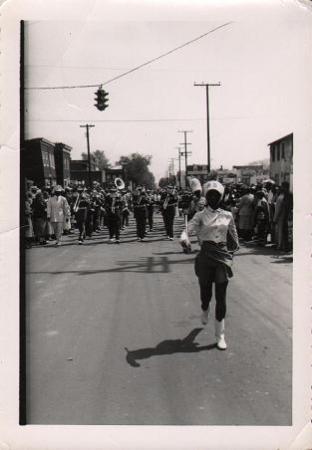

Well, in 1946, along with other fellows, we started a football team called the Alexandria Rams. , . . . . and in [19]50 we had a chance to play integrated football. They wouldn’t let us play in Alexandria, so we had to play our first game in Mount Vernon, . . . in Fairfax County, at Mount Vernon High School stadium down on Route 1.

Courtney Brooks; interviewed by The Company of Sisters, Inc., March 21, 2002.

. . . I think, maybe, the sports was one of things that helped break down the walls of segregation in this city. Sports I think, especially football…Because we started the Alexandria Rams football team. Later on, we had quite a few white fellows who came along to play football with us and that started it.

Shirley Sanderson Steele, born 1940; interviewed by Logan Wiley, August 13, 2008:

You could see Blacks beginning to see little rays between the buttermilk, or something. You'd see people driving the post office trucks when you go to the post office. You'd see Black men and women at the counters waiting on you and you'd feel good. You'd put your shoulders back and straighten up...And I felt good [ab]out it - the equal rights.

Mary Sullivan, Del Ray resident since 1946; interviewed by Mary Baumann, September 6, 2003.

A lot of people did resent it [integration]. There really wasn’t a great amount of trouble. But just a lot of people withdrew their children and sent them to private school, I think, at the beginning.

Natalie Thompson Sanks Vaughn, a teacher, vice-principal, and principal in Alexandria City Public Schools; interviewed by Patricia Knock and Henry Mitchell, July 21, 1992:

Alexandria is a paradoxical area; you could live side by side with the whites and have no trouble. Everybody knew each other and there was no problem.

When we got ready to pair the schools we had no trouble. You can ask anybody, we had no trouble at all integrating the school. It was [the death of] Martin Luther King, and we had to get a fellow named Herman Brown…and he came over to G.W. and talked to them. Reverend Peterson was here at that time. They tried to talk to the students and, what they did, they finally calmed them down.

They integrated the teachers first. We got our first white teachers around 1965, and the Black teachers were sent to predominantly white schools, and for each one you sent, you had a white teacher…they had put all the Black children in the receiving schools, as I called them. They would take all the grades kindergarten to third. That meant all the little Black children would be traveling across town . . . See, they didn’t want to fool with the big Black children, you know. I think they were afraid of them or something.

Sgt. Lee Thomas Young, grew up in The Fort neighborhood; interviewed by Patricia Knock, November 19, 1996:

They didn’t have a public school for the Blacks then you know…and later they integrated . . .. But we had to get our own transportation any way we could to get them [students] down there – to Alexandria. Or sometimes we’d walk it…almost three or four miles.

Myriam Lechuga, immigrated from Cuba in 1967; interviewed by John Reibling, June 15, 2015:

. . . at Hammond especially, some kids did not react [to integration]…But there were occasions when kids were attacking each other…so different groups as they fed into this school were not happy that these other kids were coming in. So we would be locked into the gym. I know people who were walking the halls and hit over the head by other kids who didn’t like them. Really, because you were different or you were coming in from the other school. So initially there were problems like that. They would make announcements and we would all be locked into the gym and then we would be sent home.”

Mabel Lyles, born 1927; interviewed by Phyllis Adams, March 28, 2002:

This was 1954, and the Supreme Court decision came down…When we returned to school in 1955, we got a directive from the state that Virginia was not changing…We went from pupil placement to transfers, if they wanted to go to different schools. I stayed at Lyles-Crouch [inaudible] 1958. And I taught two years there. We were going through the testing. Spring of 1960, a team of white and black auditors came out to test the black pupils. At that time I was teaching fifth grade again…And in that class, that was tested—we had prepared for it—and those students tested better than any other fifth grade class in the city...Of course, I am proud of that, that they tested well.

Colored Rosemont

Colored Rosemont was a tight-knit neighborhood of African American homeowners spanning a four-block area on either side of Wythe Street between West and Fayette Streets. Virginia Thomas, a white woman who inherited the property when her father passed away, sold the plots and houses to African American families starting in 1929. At a time when redlining and restrictive covenants prevented the majority of African Americans from owning a home, Colored Rosemont evolved into a middle-class African American neighborhood. In the early 1960s, residents organized against plans to redevelop half of the neighborhood, and reached a compromise with the City of Alexandria to maintain half of that block for individual ownership.

Beatrice C. Taylor, born in 1935, raised in Colored Rosemont; interviewed by Francesco De Salvatore, January 25, 2023:

It’s on Wythe Street. That’s where I was raised. And it’s not a large area. Maybe about six blocks. And it was just a community, a small community where everybody looked out for everybody. We all played together. When we left our neighborhood, the Rosemont…the girls, we always left together and it was time to come back, we had to come back home together. Basically, most of us attended Roberts Memorial United Methodist church, and that was out on South Washington Street…We all attended Parker Gray High School…I started Miss Martha’s Miller’s kindergarten, and I think that was probably the only kindergarten in the city for blacks in Alexandria.